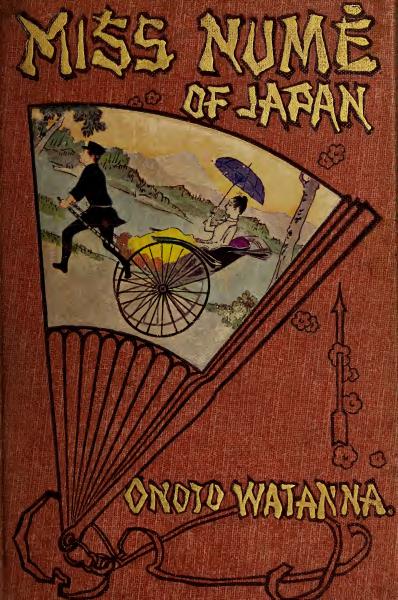

Miss Numè of Japan

i

INTRODUCTION.

The fate of an introduction to a book seems not only to fall short of

its purpose, but to offend those whose habit it is to criticise before

they read. Once I heard an old man say, “It is dangerous to write for

the wise. They strike warm hands with form, but shrug a cold shoulder at

originality.” I do not think, though, that this book was written for the

“wise,” for the men and women whose frosty judgment would freeze the

warm current of a free and almost careless soul. It was written for the

imaginative, and they alone are the true lovers of story and song. Onoto

Watanna plays upon an instrument new to our ears, quaintly Japanese, an

air at times simple and sweet, as tender as the chirrup of a bird in

love, and then as wild as the scream of a hawk. Mood has been her

teacher; impulse has dictated her style. She has inherited the spirit of

the orchard in bloom. Her art is the grace of the wild vine, under no

obligation to a gardener, but with a charm that the gardener could not

impart. A monogram wrought by nature’s accident upon the golden leaf of

autumn, does not belong to the world of letters, but it inspires more

feeling and more poetry than a library squeezed out of man’s tired

brain. And this book is not unlike an autumn leaf blown from a forest in Japan.

OPIE READ.

Chicago, January, 1899.

CHAPTER I. PARENTAL AMBITIONS.

When Orito, son of Takashima Sachi, was but ten years of age, and Numè,

daughter of Watanabe Omi, a tiny girl of three, their fathers talked

quite seriously of betrothing them to each other, for they had been

great friends for many years, and it was the dearest wish of their lives

to see their children united in marriage. They were very wealthy men,

and the father of Orito was ambitious that his son should have an

unusually good education, so that when Orito was seventeen years of age,

he had left the public school of Tokyo and was attending the Imperial

University. About this time, and when Orito was at home on a vacation,

there came to the little town where they lived, and which was only a

very short distance from Tokyo, certain foreigners from the West, who

rented land from Sachi and became neighbors to him and to Omi.

Sachi had always taken a great deal of interest in these foreigners,

many of whom he had met quite often while on business in Tokyo, and he

was very

6 much pleased with his new tenants, who, in spite of their

barbarous manners and dress, seemed good-natured and friendly. Often in

the evening he and Omi would walk through the valley to their neighbors’

house, and listen to them very attentively while they told them of their

home in America, which they said was the greatest country in the world.

After a time the strange men went away, though neither Sachi nor Omi

forgot them, and very often they talked of them and of their foreign

home. One day Sachi said very seriously to his friend:

“Omi, these strangers told us much of their strange land, and talked of

the fine schools there, where all manner of learning is taught. What say

you that I do send my unworthy son, Orito, to this America, so that he

may see much of the world, and also become a great scholar, and later

return to crave thy noble daughter in marriage?”

Omi was fairly delighted with this proposal, and the two friends talked

and planned, and then sent for the lad.

Orito was a youth of extreme beauty. He was tall and slender; his face

was pale and oval, with features as fine and delicate as a girl’s. His

was not merely a beautiful face; there was something else in it, a

certain impassive look that rendered it almost startling in its

wonderful inscrutableness. It was not expressionless, but

unreadable—the face of one with the noble blood of the Kazoku and

Samourai—pale, refined, and emotionless.

He bowed low and courteously when he entered,

7 and said a few words of

gentle greeting to Omi, in a clear, mellow voice that was very pleasing.

Sachi’s eyes sparkled with pride as he looked on his son. Unlike Orito,

he was a very impulsive man, and without preparing the boy, he hastened

to tell him at once of their plans for his future. While his father was

speaking Orito’s face did not alter from its calm, grave attention,

although he was unusually moved. He only said,

“What of Numè, my

father?”Sachi and Omi beamed on him.

“When you return from this America I will give you Numè as a bride,”

said Omi.

“And when will that be?” asked Orito, in a low voice.

“In eight years, my son, and you shall have all manner of learning

there, which cannot be acquired here in Tokyo or in Kyushu, and the

manner of learning will be different from that taught anywhere in Japan.

You will have a foreign education, as well as what you have learned here

at home. It shall be thorough, and therefore it will take some years.

You must prepare at once, my son; I desire it.”

Orito bowed gracefully and thanked his father, declaring it was the

chief desire of his life to obey the will of his parent in all things.

Now Numè was a very peculiar child. Unlike most Japanese maidens, she

was impetuous and wayward. Her mother had died when she was born, and

she had never had any one to guide or direct her, so that she had grown

up in a careless,

8 happy fashion, worshiped by her father’s servants,

but depending entirely upon Orito for all her small joys. Orito was her

only companion and friend, and she believed blindly in him. She told him

all her little troubles, and he in turn tried to teach her many things,

for, although their fathers intended to betroth them to each other as

soon as they were old enough, still Numè was only a little girl of ten,

whilst Orito was a tall man-youth of nearly eighteen years. They loved

each other very dearly; Orito loved Numè because she was one day to be

his little wife, and because she was very bright and pretty; whilst Numè

loved big Orito with a pride that was pathetic in its confidence.

That afternoon Numè waited long for Orito to come, but the boy had gone

out across the valley, and was wandering aimlessly among the hills,

trying to make up his mind to go to Numè and tell her that in less than

a week he must leave her, and his beautiful home, for eight long years.

The next day a great storm broke over the little town, and Numè was

unable to go to the school, and because Orito had not come she became

very restless and wandered fretfully about the house. So she complained

bitterly to her father that Orito had not come. Then Omi, forgetting all

else save the great future in store for his prospective son-in-law, told

her of their plans. And Numè listened to him, not as Orito had done,

with quiet, calm face, for hers was stormy and rebellious, and she

sprang to her father’s side and caught his hands sharply in her little

ones, crying out passionately:

9

“No! no! my father, do not send Orito away.”

Omi was shocked at this display of unmaidenly conduct, and arose in a

dignified fashion, ordering his daughter to leave him, and Numè crept

out, too stunned to say more. About an hour after that Orito came in,

and discovered her rolled into a very forlorn little heap, with her head

on a cushion, and weeping her eyes out.

“You should not weep, Numè,” he said. “You should rather smile, for see,

I will come back a great scholar, and will tell you of all I have

seen—the people I have met—the strange men and women.” But at that

Numè pushed him from her, and declared she wanted not to hear of those

barbarians, and flashed her eyes wrathfully at him, whereat Orito

assured her that none of them would be half as beautiful or sweet as his

little Numè—his plum blossom; for the word Numè means plum blossom in

Japanese. Finally Numè promised to be very brave, and the day Orito left

she only wept when no one could see her.

And so Orito sailed for America, and entered a great college called

“Harvard.” And little Numè remained in Japan, and because there was no

Orito now to tell her thoughts to, she grew very subdued and quiet, so

that few would have recognized in her the merry, wayward little girl who

had followed Orito around like his very shadow. But Numè never forgot

Orito for one little moment, and when every one else in the house was

sound asleep, she would lie awake thinking of him.

10

CHAPTER II. CLEO.

“No use looking over there, my dear. Takie has no heart to break—never

knew a Jap that had, for that matter—cold sort of creatures, most of

them.”

The speaker leaned nonchalantly against the guard rail, and looked

half-amusedly at the girl beside him. She raised her head saucily as her

companion addressed her, and the willful little toss to her chin was so

pretty and wicked that the man laughed outright.

“No need for you to answer in words,” he said. “That wicked, willful

look of yours bodes ill for the Jap’s—er—heart.”

“I would like to know him,” said the girl, slowly and quite soberly.

“Really, he is very good-looking.”

“Oh! yes—I suppose so—for a Japanese,” her companion interrupted.

The girl looked at him in undisguised disgust for a moment.

“How ignorant you are, Tom!” she said, impatiently; “as if it makes the

slightest difference what nationality he belongs to. Mighty lot you

know about the Japanese.”

Tom wilted before this assault, and the girl took advantage to say:

“Now, Tom, I want to know11 Mr.—a—a—Takashima. What a name! Go, like

the dear good boy you are, and bring him over here.”Tom straightened his shoulders.

“I utterly, completely, and altogether refuse to introduce you, young

lady, to any other man on board this steamer. Why, at the rate you’re

going there won’t be a heart-whole man on board by the time we reach

Japan.”

“But you said Mr. Ta—Takashima—or ‘Takie,’ as you call him, had no

heart.”

“True, but you might create one in him. I have a great deal of

confidence in you, you know.”

“Oh! Tom, don’t be ridiculous now. Horrid thing! I believe you just

want to be coaxed.”

Tom’s good-natured, fair face expanded in a broad smile for a moment.

Then he tried to clear it.

“Always disliked to be coaxed,” he choked.

“Hem!” The girl looked over into the waters a moment, thinking. Then she

rose up and looked Tom in the face.

“Tom, if you don’t I’ll go over and speak to him without an

introduction.”

“Better try it,” said Tom, aggravatingly. “Why, you’d shock him so much

he wouldn’t get over it for a year. You don’t know these Japs as I do,

my dear—dozens of them at our college—awfully strict on subject of

etiquette, manners, and all that folderol.”

“Yes, but I’d tell him it was an American custom.”

12

“Can’t fool Takashima, my dear. Been in America eight years now—knows

a thing or two, I guess.”

Takashima, the young Japanese, looked over at them, with the unreadable,

quiet gaze peculiar to the better class Japanese. His eyes loitered on

the girl’s beautiful face, and he moved a step nearer to them, as a

gentleman in passing stood in front, and for a moment hid them from him.

“He is looking at us now,” said the girl, innocently.

Tom stared at her round-eyed for a moment.

“How on earth do you know that? Your head is turned right from him.”

Again the saucy little toss of the chin was all the girl’s answer.

“He’s right near us now. Tom, please, please—now’s your chance,” she

added, after a minute.

The Japanese had come quite close to them. He was still looking at the

girl’s face, as though thoroughly fascinated with its beauty. A sudden

wind came up from the sea and caught the red cape she wore, blowing it

wildly about her. It shook the rich gold of her hair in wondrous soft

shiny waves about her face, as she tried vainly to hold the little cap

on her head. It was a sudden wild wind, such as one often encounters at

sea, lasting only for a moment, but in that moment almost lifting one

from the deck. The girl, who had been clinging breathlessly to the

railing, turned toward Takashima, her cheeks aflame with excitement, and

as the violent gust subsided, they smiled in each other’s faces.

Tom relented.

13

“Hallo! Takie—you there?” he said, cordially. “Thought you’d be laid

up. You’re a pretty good sailor, I see.” Then he turned to the girl and

said very solemnly and as if they had never even discussed the subject

of an introduction, “Cleo, this is my old college friend, Mr.

Takashima—Takie, my cousin, Miss Ballard.”

“Will you tell me why,” said the young Japanese, very seriously, “you

did not want that I should know your cousin?”

“Don’t mind Tom,” the girl answered, with embarrassment, as that

gentleman threw away his cigar deliberately; and she saw by his face

that he intended saying something that would mislead Takashima, for he

had often told her of the direct, serious and strange questions the

Japanese would ask, and how he was in the habit of leading him off the

track, just for the fun of the thing, and because Takashima took

everything so seriously.

“Why—a—” said Tom, “the truth of the matter is—my cousin is a—a

flirt!”

“Tom!” said the girl, with flaming cheeks.

“A flirt!” repeated the Japanese, half-musingly. “Ah! I do not like a

flirt—that is not a nice word,” he added, gently.

“Tom is just teasing me,” she said; and added, “But how did you know Tom

did not want you to know me?”

“I heard you tell him that you want to know me, and I puzzle much myself

why he did not want.”

“I was sorry for you in advance, Takie,” said Tom, wickedly, and then

seeing by the girl’s face

14 that she was getting seriously offended, he

added:

“Well, the truth is—er—Cleo—is—a so—young, don’t you know.

One can’t introduce their female relatives to many of their male

friends. You understand. That’s how you put it to me once.”

“Yes!” said Takashima, “I remember that I tell you of that. Then I am

most flattered to know your relative.”

As Tom moved off and left them together, feeling afraid to trust himself

for fear he would make things worse, he heard the gentle voice of the

Japanese saying very softly to the girl:

“I am most glad that you do not flirt. I do not like that word. Is it

American?”

Tom chuckled to himself, and shook his fist, in mock threat, at Cleo.

15

CHAPTER III. WHO CAN ANALYZE A COQUETTE?

Cleo Ballard was a coquette; such an alluring, bright, sweet, dangerous

coquette. She could not have counted her adorers, because they would

have included every one who knew her. Such a gay, happy girl as she was;

always looking about her for happiness, and finding it only in the

admiration and adoration of her victims; for they

were victims, after

all, because, though they were generally willing to adore in the

beginning, she nevertheless crushed their hopes in the end; for that is

the nature of coquettes. Hers was a strange, paradoxical nature. She

would put herself out, perhaps go miles out of her way, for the sake of

a new adorer, one whose heart she knew she would storm, and then perhaps

break. She would do this gayly, thoughtlessly, as unscrupulously and

impetuously as she tore the little silk gloves from her hands because

they came not off easily. And yet, in spite of this, it broke her heart

(and, after all, she had a heart) to see the meanest, the most

insignificant of creatures in pain or trouble. With a laugh she pulled

the heart-strings till they ached with pain and pleasure commingled; but

when the poor heart burst with the tension, then she would run shivering

away, and hide herself, because so long as she

16 did not see the pain she

did not feel it. Who can analyze a coquette?

Then, too, she was very beautiful, as all coquettes are. She had

sun-kissed, golden-brown hair,—dark brown at night and in the shadow,

bright gold in the daytime and in the light. Her eyes were dark blue,

sombre, gentle eyes at times, wicked, mischievous, mocking eyes at

others. Of the rest of her face, you do not need to know, for when one

is young and has wonderful eyes, shiny, wavy hair and even features, be

sure that one is very beautiful.

Cleo Ballard was beautiful, with the charming, versatile, changeable,

wholly fascinating beauty of an American girl—an American beauty.

And now she had a new admirer, perhaps a new—lover. He was so different

from the rest. It had been an easy matter for her to play with and turn

off her many American adorers, because most of them went into the game

of hearts with their eyes open, and knew from the first that the girl

was but playing with them. But how was she to treat one who believed

every word she said, whether uttered gayly or otherwise, and who, in his

gentle, undisguised way, did not attempt, even from the beginning, to

hide from her the fact that he admired her so intensely?

Ever since the day Tom Ballard had introduced Takashima to her, he had

been with her almost constantly. Among all the men, young and old, who

paid her court on the steamer, she openly favored the Japanese. Most

Japanese have their

17 full share of conceit. Takashima was not lacking in

this. It was pleasant for him to be singled out each day as the one the

beautiful American girl preferred to have by her. It pleased him that

she did not laugh or joke so much when with him, but often became even

as serious as he, and he even enjoyed hearing her snub some of her

admirers for his sake.

“Cleo,” Tom Ballard said to her one day, as the Japanese left her side

for a moment, “have mercy on Takashima; spare him, as thou wouldst be

spared.”

She flushed a trifle at the bantering words, and looked out across the

sea.

“Why, Tom! he understands. Didn’t you say he had lived eight years in

America?”

Tom sighed. “Woman! woman! incorrigible, unanswerable creature!”

After a time Cleo said, almost pleadingly, as if she were trying to

defend herself against some accusation:

“Really, Tom, he is so nice. I can’t help myself. You haven’t the

slightest idea how it feels to have any one—any one like that—on the

verge of being in love with you.”

Takashima returned to them, and took his seat by the girl’s side.

“To-night,” he told her, “they are going to dance on deck. The band will

play a concert for us.”

Cleo smiled whimsically at his broken English, for, in spite of his long

residence in America, he still tripped in his speech.

18

“Do you dance?” she asked, curiously.

“No! I like better to watch with you.”

“But I dance,” she put in, hastily.

Takashima’s face fell. He looked at her so dejectedly that she laughed.

“Life is so serious to you, is it not, Mr. Takashima? Every little thing

is of moment.”

He gravely agreed with her, looking almost surprised that she should

consider this strange.

“We are always taught,” he said, gently, “that it is the little things

of life which produce the big; that without the little we may not have

the big. So, therefore, we Japanese measure even the smallest of things

just as we do the large things.”

Cleo repeated this speech later to Tom, and an Englishman who had been

paying her a good deal of attention. They both laughed, but she felt

somewhat ashamed of herself for repeating it.

“I suppose, then, you will not dance,” said the Englishman. Cleo did not

specially like him. She intended fully to dance, that night, but a

contrary spirit made her reply, “No; I guess I will not.”

She glanced over to where the young Japanese sat, a little apart from

the others. His cap was pulled over his eyes, but the girl felt he had

been watching her. She recrossed the deck and sat down beside him.

“Will you be glad,” she asked him, “when we reach Japan?”

A shadow flitted for a moment across his face before he replied.

“Yes, Miss Ballard, most glad. My country is19 very beautiful, and I wish

very much to see my home and my relations again.”

“You do not look like most Japanese I have met,” she said, slowly,

studying his face with interest. “Your eyes are larger and your features

more regular.”

“That is very polite that you say,” he said.

The girl laughed. “No! I didn’t say it for politeness,” she protested,

“but because it is true. You are really very fine looking, as Tom would

say;” she halted shyly for a moment, and then added, “for—for a

Japanese.”

Takashima smiled. “Some of the Japanese do not have very small eyes.

Very few of the Kazoku class have them. That it is more pretty to have

them large we do not say in Japan.”

“Then,” said the girl, mischievously, “you are not handsome in Japan.”

This time Takashima laughed outright.

“I will try and be modest,” he said. “Therefore, I will let you be the

judge when we arrive there. If you think I am, as you say, handsome,

then shall I surely be.”

20

CHAPTER IV. THE DANCE ON DECK.

That evening the decks presented a gala appearance. On every available

place, swung clear across the deck, were Japanese and Chinese lanterns

and flags of every nation. The band commenced playing even while they

were yet at dinner, and the strains of music floated into the

dining-room, acting as an appetizer to the passengers, and giving them

anticipation of the pleasant evening in store. About seven o’clock the

guests, dressed in evening costume, began to stroll on deck, and as the

darkness slowly chased away the light, the pat of dainty feet mingled

with the strains of music, the sough of the sea and the sigh of the

wind. Lighted solely by the moon and the swinging lanterns, the scene on

deck was as beautiful as a fairyland picture.

Cleo Ballard was not dancing. She was sitting back in a sheltered corner

with Takashima. Her eyes often wandered to the gay dancers, and her

little feet at times could scarcely keep still. Yet it was of her own

free will that she was not dancing. When she had first come on deck she

was soon surrounded with eager young men ready to be her partners in the

dance. The girl had stood laughingly in their midst, answering this one

with saucy wit and repartee, snubbing that one (when he

21 deserved it),

and looking nameless things at others. And as she stood there laughing

and talking gayly, a girl had passed by her and made some light remark.

She did not catch the words. A few moments after she saw the same girl

sitting alone with Takashima, and there was a curiously stubborn look

about Cleo’s eyes when she turned them away.

“Don’t bother me, boys,” she said. “I don’t believe I want to dance just

yet. Perhaps later, when it gets dark. I believe I’ll sit down for a

while anyhow.”

She found her way to where Takashima and Miss Morton were sitting. Miss

Morton was talking very vivaciously, and the Japanese was answering

absently. As Cleo came behind him and rested her hand for a moment on

the back of his deck-chair, he started.

“Ah, is it you?” he said, softly. “Did you not say that you would

dance?”

“It is a little early yet,” the girl answered. “See, the sun has not

gone down yet. Let us watch it.”

They drew their deck-chairs quite close to the guard-rail, and watched

the dying sunset.

“It is the most beautiful thing on earth,” said Cleo Ballard, and she

sighed vaguely.

The Japanese turned and looked at her in the semi-darkness.

“Nay! you are more beautiful,” he said, and his face was eloquent in

its earnestness. The girl turned her head away.

22

“Tell me about the women in Japan,” she said, changing the subject.

“Are not they very beautiful?”

Takashima’s thoughtful face looked out across the ocean waste. “Yes,” he

said slowly; “I have always thought so. Still, none of them is as

beautiful as you are—or—or—as kind,” he added, hesitatingly.

The man’s homage intoxicated Cleo. She knew all the men worth knowing on

board—had known many of them in America. She had tired, bored herself,

flirting with them. It was a refreshment to her now to wake the

admiration—the sentiment—of this young Japanese, because they had told

her he always concealed his emotions so skillfully. Not for a moment did

she, even to herself, admit that it was more than a mere passing fancy

she had for him. She could not help it that he admired her, she told

herself, and admiration and homage were to her what the sun and rain is

to the flowers. That Takashima could never really be anything to her she

knew full well; and yet, with a woman’s perversity, she was jealous even

at the thought that any other woman should have the smallest thought

from him. It is strange, but true, that a woman often demands the entire

homage and love of a man she does not herself actually love, and only

because of the fact that he does love her. She resents even the smallest

wavering of his allegiance to her, even though she herself be impossible

for him. It was because she fancied she saw a rival in Miss Morton that

for a moment she became possessed of a wish

23 to monopolize him entirely,

so long as she would be with him.

When Miss Morton, who soon perceived that she was not wanted, made a

slight apology for leaving them, Cleo turned and said, very sweetly:

“Please don’t mention it.”

24

CHAPTER V. HER GENTLE ENEMY.

Enemies are often easier made than friends. Fanny Morton was not an

agreeable enemy to have. She was one of those women who were constantly

on the look-out for objects of interest. She was interested in

Takashima, as was nearly every one who met him. In the first place,

Takashima was a desirable person to know; a graduate of Harvard

University, of irreproachable manners, and high breeding, wealthy,

cultured, and even good-looking. Moreover, the innate goodness and

purity of the young man’s character were reflected in his face. In fact,

he was a most desirable person to know for those who were bound for the

Land of Sunrise. That he could secure them the entrée to all desirable

places in Japan, they knew. For this reason if for no other Takashima

was popular, but it was more on account of the genuineness of the young

man, and his gentle courtesy to every one, that the passengers sought

him out and made much of him on the steamer. And it was partly because

he was so popular that Cleo Ballard, with the usual vanity of woman,

found him doubly interesting. In his gentle way he had retained all of

them as his friends, in spite of the fact that he had attached himself

almost entirely to

25 Miss Ballard. On the other hand, the girl had

suffered a good deal from the malicious jealousy of some of the women

passengers, who made her a target for all their spite and spleen. But

she enjoyed it rather than otherwise.

“Most people do not like me as well as you do, Mr. Takashima,” she said

once. He had looked puzzled a moment, and she had added, “That is

because I don’t like everybody. You ought to feel flattered that I like

you.”

Fanny Morton could not forgive Cleo the half-cut of the evening of the

hop. A few days afterwards she said to a group of women as they lay back

in their deck-chairs, languidly watching the restless waves, “I wonder

what Cleo Ballard’s little game is with young Takashima?”

She had told them of the conversation on deck, of the young Japanese’s

peculiar familiarity and homage in addressing her, and of the flowery,

though earnest, compliments he had paid her.

“She must be in love with him,” one of the party volunteered.

“No, she is not,” contradicted an old acquaintance of Cleo’s, “because

Cleo could not be in love with any one. The girl never had any heart.”

“I thought she was engaged to Arthur Sinclair, and was going out to join

him in Tokyo,” put in an anxious-looking little woman who had spent

almost the entire voyage on her back, being troubled with a fresh

convulsion of seasickness every time the sea got the least bit rough. It

is wonderful what a lot of information is often to be got out of one of

these

26 invalids. During the greater part of the voyage they merely

listen to all about them, and, as a rule, the rest are inclined to

regard them as so many dummies. Then, toward the close of the voyage,

they will surprise you with their knowledge on a question that has never

been settled.

“That is news,” said Cleo’s old acquaintance, sitting up in her chair,

and regarding the little woman with undisguised amazement. “Who told

you, my dear?”

“I thought I heard her discussing it with her cousin the other day,” the

woman answered, with visible pleasure that she was now an object of

interest.

“My dear,” repeated the old acquaintance once more, settling her ample

form in the canvas chair, “really, I must have been stupid not to have

guessed this. Why, of course, I understand now. That was what all that

finery meant in Washington, I suppose. That is why her mother has been

so mysteriously uneasy about Cleo’s—and I must say it now—outrageous

flirtation with the Japanese. Every time she has been able to come on

deck—and, poor thing, it has not been often through the voyage so

far—she has called Cleo away from Mr. Takashima, and I’ve even heard

her reprove her, and remonstrate with her. Well! well!”

Fanny Morton was smiling as she stole away from the party.

27

CHAPTER VI. A VEILED HINT.

Always, after dinner, the young Japanese would come on deck, having

generally finished his meal before most of the others, and rarely

sitting through the eight or ten courses. Like the rest of his

countrymen, he was a passionate lover of nature. Sunsets are more

beautiful at sea, when they kiss and mirror their wonderful beauty in

the ocean, than anywhere else, perhaps.

Fannie Morton found him in his favorite seat—back against a small

alcove, his small, daintily manicured fingers resting on the back of a

chair in front of him.

She pulled a chair along the deck, and sat down beside him.

“You are selfish, Mr. Takashima,” she said, “to enjoy the sunset all

alone.”

“Will you not enjoy it also?” he asked, quite gravely. “I like much

better, though,” he continued, seeing that she had come up more to talk

than to enjoy the sunset, “to look at the skies and the water rather

than to talk. It is most strange, but one does not care to talk as much

at sea as on land when the evenings advance.”

“And yet,” Miss Morton said, “I have often heard Miss Ballard’s voice

conversing with you in the evening.”

28

The Japanese was silent a moment. Then he said, very simply and

honestly, “Ah, yes, but I would rather hear her voice than all else on

earth. She is different to me.”

The girl reddened a trifle impatiently.

“Most men love flirts,” she said, sharply.

The Japanese smiled quietly, confidently.

“Yes, perhaps,” he said, vaguely, purposely misleading her.

Tom Ballard’s hearty voice broke in on them.

“Well,” he said, cheerfully, “thought I’d find Cleo with you, Takie,”

and then, smiling gallantly at Miss Morton, “but really, I see you’ve

got ‘metal more attractive.’” He winked, and continued, “Cousins are

privileged beings. Can say lots of things no one else dare.”

Fanny Morton’s face brightened. She was a pretty girl, with pale brown

hair, and a bright, sharp face.

“Oh, now, Mr. Ballard, you are flattering. What would Miss Cleo say?”

Tom scratched his head. “She would prove, I dare say, that I

was—a—lying.”

The play on words had been entirely lost on Takashima, who had become

absorbed in his own reveries. Then Miss Morton’s sharp words caught his

ear, and he turned to hear what she was saying. She had mentioned the

name of an old American friend of his, who had gone to Japan some years

before.

“I suppose,” Miss Morton had said,

“she will be pretty glad when the

voyage is over.” She had

29 paused here, and Tom had prompted her with a

quick query,

“Why?”

“Oh! for Arthur Sinclair’s sake,” she had retorted, and laughingly left

them.

Casually, Tom turned to Takashima. “Remember Sinclair, Takie? Great big

fellow at Harvard—in for all the races—rowing—everything going—in

fact, all-round fine fellow?”

“Yes.”

“Nice—fellow.”

“Yes.”

“Er—Cleo—that is, both Cleo and I, are old friends of his, you know.”

Takashima’s face was still enigmatical.

Cleo had had a headache that evening, and had returned to her stateroom

after dinner. The water was rough, and few of the passengers remained on

deck. Quite late in the evening, Tom went up. The sombre, silent figure

of the Japanese was still there. He had not moved.

“Past eleven,” Tom called out to him, and the gently modulated voice of

the Japanese answered, “Yes; I will retire soon.”

30

CHAPTER VII. JEALOUSY WITHOUT LOVE.

The next day Cleo rallied Takashima because he was unusually quiet, and

asked him the cause. He turned and looked at her very directly.

“Will you tell me, Miss Ballard,” he said, “why Mr. Sinclair will be so

overjoyed that you come to Japan?”

The abrupt question startled the girl. She flushed a violent, almost

angry red, and for a moment did not reply. Then she recovered herself

and said: “He is a very dear friend of ours.”

The Japanese looked thoughtfully at her. There was an embarrassed flush

on her face. Again he questioned her very directly, still with his eyes

on her face.

“Tell me, Miss Ballard, also, do you flirt only with me?”

Cleo’s face was averted a moment. With an effort she turned toward him,

a light answer on the tip of her tongue. Something in the earnest,

questioning gaze of the young man held her a moment and changed her gay

answer. Her voice was very low:

“No,” she said. “Please don’t believe that of me.”

She understood that some one had been trying to

31 poison him against her.

Her eyes were dewy—with self-pity, perhaps, for at that moment the

coquette in her was subdued, and the natural liking, almost sentiment,

she had for Takashima was paramount. A silence fell between them.

Takashima broke it after a while to say, very gently:

“Will you forgive

me, Miss Ballard?”“There is nothing to forgive.”

“Ah! yes,” said Takashima, sadly, “because I have misjudged you so?” His

voice was raised in a half-question. The girl’s eyes were suffused.

“Let us not talk of it any more,” he continued, noticing her distress

and embarrassment. “I will draw your chair back here and we will talk.

What will we talk of? Of America—of Japan? Of you—and of myself?”

“My life has been uninteresting,” she said; “let us not talk of it

to-night,—but tell me about yours instead. You must have some very

pretty remembrances of Japan. Eight years is not such a long time, after

all.”

“No; that is true, and yet one may become almost a different being

during that time.” He paused thoughtfully. “Still, I have many beautiful

remembrances of my home—all my memories, in fact, are sweet of it.”

Again he paused to think, and continued slowly: “I will also have

beautiful memories of America.”

“Yes, but they will be different,” said the girl, “for, of course,

America is not your home.”

“One often, though, becomes homesick—let us call it—for a country

which is not our own, but32 where we have sojourned for a time,” he

rejoined, quickly.

“Then, if Japan is as beautiful as they say it is, I will doubtless be

longing for it when I return to America.”

A flush stole to the young man’s eager face.

“Ah! Miss Ballard, perhaps if you will say that when you have lived

there a while, I might find courage to say that which I cannot say now.

I would wish first of all to know how you like my home.”

The girl put her hands at the back of her head, and leaned back in the

deck-chair with a sudden nervous movement.

“Let us wait till then,” she said, hastily. “Tell me now, instead, what

is your most beautiful memory of Japan?”

“My pleasantest memory,” he said, “is of a little girl named Numè. She

was only ten years old when I left home, but she was bright and

beautiful as the wild birds that fly across the valleys and make their

home close by where we lived.”

A flush had risen to the girl’s face. She stirred nervously, and there

was a slight faltering in her speech as she said: “Tom once told me of

her—he said you had told him—that you had told him—you were betrothed

to her.”

She had expected him to look abashed for a moment, but his face was as

calm as ever.

“I will not know that till I am home. My plans are unformed.” He looked

in her face. “They depend a great deal on you,” he continued.

33

For a moment the girl’s lips half-parted to tell him of her own

betrothal, but she could not summon the courage to do so while he looked

at her with such confidence and trust; besides, her woman’s vanity was

touched.

“Tell me about Numè,” she said, and there was the least touch of pique

in her voice.

“Her father and mine are neighbors, and very dear friends. I have known

her all my life. When she was a little girl I used to carry her on my

shoulders over brooks and through the woods and mountain passes, because

she was so little, and I was always afraid she would fall and hurt

herself.”

Cleo was silent now. She scarcely stirred while the young man was

speaking, but listened to him with strange interest. Takashima

continued: “I used to tell her I would some day be her Otto (husband),

and because she was so very fond of me that pleased her very much, and

when I said so to our fathers, it pleased them also.”

The girl was nervously twisting her little handkerchief into odd knots.

She was not looking at Takashima.

“How queer,” she said, “that our childhood memories are sometimes so

clear to us! We so often look back on them and think how—how absurd we

were then. Don’t you think there is really more in the past to regret

than anything else?”

Takashima looked at her in surprise.

“No,” he said; almost shortly, “I have nothing to regret.”

“And yet,” she persisted,

“neither of you was34 old enough to—to care

for the other truly.” Her words were irrelevant, and she knew it.

“We were inseparable always,” the young man answered. “We were children,

both of us, but in Japan very often we are always children—always young

in heart.”

Cleo could not have told why she felt the sudden overwhelming rebellion

against his allegiance to Numè, even though she knew only too well that

Takashima’s heart was safe in her own keeping. With a woman’s perversity

and delight in being constantly assured of his love for her in various

ways, in dwelling on it to feed her vanity, and yes, in wishing to hear

the man who loved her disclaim—even ridicule—one whom in the past he

might have cared for, she said:

“Do you love her?”

“Love?” the Japanese repeated, dwelling softly on the word. “That is not

the word now, Miss Ballard. I have only known its meaning since I have

met you,” he added, gently.

The girl’s heart beat with a pleasurable wildness. It was sweet to hear

these words from the lips of one who hesitated always so deferentially

from speaking his feelings; from one who a moment before had filled her

with a fear that, after all, another might interest him just as she had

done; for coquettes are essentially selfish.

“You will not marry her?” she questioned, in a low voice.

She could not restrain the almost pleading tone that crept into her

voice; for though she kept

35telling herself that they could never be

anything to each other, and that she already loved another, yet, after

all, was she so sure of her heart? The Japanese was silent.

“That will

depend,” he said, slowly.

“It is the wish of our fathers. They have

always looked forward to it.” His voice was very sad as he added:

“Perhaps I should grow to love her. Surely, I would try, at least, to do

my duty to my parents.”With a sudden effort the girl rose to her feet.

“It would be a cruel thing to do,” she said, “cruel for her and for you.

It would be fair to no one. You do not love; therefore, you should not

marry her.” Her beautiful eyes challenged him. A wild hope crept into

the Japanese’s heart that the girl must surely return his feeling for

her, or she would not speak so. He was Americanized, and man of the

world enough, to understand somewhat of these things. He purposely

misled her, taking pleasure in the girl’s evident resentment at his

marriage with Numè.

“I would never marry a man I did not love,” she continued. “No! I would

have to love him with my whole heart.”

“It is different in Japan,” he said, quietly. “There we do not always

marry for love, but rather to please the parents. We try always to love

after marriage—and often we succeed.”

“Your customs are—are—barbarous, then,” Cleo said, defiantly. “We in

America could not understand them.”

There was a vague reproach now in her voice. The Japanese had risen

also. He was smiling, as

36 he looked at the girl. Perhaps she felt

unconsciously the tenderness of that look, for she turned her own head

away persistently.

“Miss Ballard,” he said, softly,—“Miss Cleo—I do not disagree with

you, after all, as you think. It is true, as you say—there should be no

marriage without love.”

“And yet you are willing to follow the ancient customs of your country,”

she said, half-pettishly—almost scornfully.

“I did not say that,” he said, smiling.

“Yes, but you make one believe it,” she said.

“I did not mean to. I wanted only that you should believe that it might

be so for my father’s sake, if—if the one I did love was—impossible to

me.” There was a piercing passion in his voice that she had not thought

him capable of.

One of those inexplicable, sudden waves of gentleness and tenderness

that sometimes sweep over a woman, came over her. She turned and faced

Takashima with a look on her face that would have made the coldest

lover’s heart throb with delight and hope.

“You must be always sure—always sure she is—she is impossible.”

She was appalled at her own words as soon as they were uttered.

The Japanese had taken a step nearer to her. He half held his hands out.

“I am going below,” she said, with sudden fright, “I—I—indeed, I don’t

know what I’m talking about.”

37

CHAPTER VIII. THE MAN SHE DID LOVE.

When she reached her stateroom, she threw herself on the couch, being

overcome by a sudden weakness. She could not understand nor recognize

herself. It was impossible that she was in love with Takashima, for she

already loved another; and yet she could not understand why she should

feel so keenly about Takashima, nor why it hurt her,—the idea of his

caring for any one else. Was it merely the selfishness and vanity of a

coquette? Cleo could scarcely remember a time, since she was old enough

to understand that man was woman’s natural plaything, that she had not

thoughtlessly and gayly coquetted, flirted and led on all the men who

had dared to fall in love with her. There was so seldom a real pang with

her, because she had seldom permitted any affair to go beyond a certain

length. That is, almost from the beginning she would let them know that

her heart was not touched—that she was merely playing with them,

because she could not help being a flirt. Then Arthur Sinclair had come

into her life. As she thought of him a wonderful tenderness stole over

her face, a tenderness that Takashima had never been able to call there.

It had been a case of love on her side almost from

38 the first night they

had met. But with the man it was different; and perhaps it was because

of the fact that he at first had been almost indifferent to her, that

the girl who had wearied of the over-attention of the other men, who had

loved her unquestioningly, and whose love had been such an easy thing to

win, specially picked him out as the one man to whom she could give her

heart. How often it happens that she who has been loved and courted by

every one, should actually love the only one who perhaps had been almost

indifferent to her! True, Sinclair had paid her a good deal of attention

from the beginning, but it was because he admired her solely on account

of her beautiful face, and because she was popular everywhere with every

one, and it touched his vanity that she should single him out.

Later, the girl’s wonderful charm had grown on him; and one night when

they stood on the conservatory balcony of her home, when the moon’s

kindly rays touched her head and lighted her face with an almost wild

beauty, when the perfume of the roses in her breast and hair had stolen

into his senses, and the great speaking eyes told the story of her

heart, Sinclair had told her he loved her. He had told her so with a

wild passion; had told her so at a time when, a moment before, he had

not himself known it. That she was wonderfully beautiful he had always

known, but he had thought himself proof against her. He was not. It came

to him that night—the knowledge of an overmastering love for her that

had suddenly possessed him—a love

39 that was so unexpected and violent

in its coming, that half of its passion was spent in that one glorious

first night, when she had answered his passionate declaration solely by

holding her hands out to him, and he had drawn her into his arms.

Sinclair had returned to his rooms that night almost dazed. Did he love

her? he asked himself. A memory came back of the girl’s wonderful

beauty, of the love that had reflected itself in her eyes and had

beautified them so. And yet he had seen her often so—she had always

been beautiful, but before that he had been unable to call up anything

more than strong admiration of her beauty. Was it not that he had drank

too much wine that night? No! he seldom did that. It was the girl’s

beauty and the knowledge that she loved him that had turned his head; it

was the wine too, perhaps, and the surroundings, the moonlight, the

flowers, their fragrance—everything combined. And then, having thought

confusedly over the whole thing, Arthur Sinclair had risen to his feet

and walked restlessly up and down his room—because he was not sure of

his own heart after all.

Cleo Ballard had known nothing of this struggle he had had with himself.

After that night he had been an ideal lover,—always considerate,

gentle, and tender. The girl’s imperious nature had melted under the

great love that had come into her life. She ceased for a time to be a

coquette. Then she was only a loving, tender woman.

It was hardly a month after this that Sinclair was appointed American

Vice-Consul at Kyoto, Japan.

40 He had told Cleo very gently of the

appointment, and they had discussed their future together. It meant

separation for a time, for Sinclair did not urge an early marriage, and

Cleo Ballard was perhaps too proud to want it.

“We will marry,” Sinclair had said, “when I am thoroughly established,

when I have something to offer you—when I can afford to keep my wife as

I would like to keep you.”

The girl had answered with half-quivering lip: “Neither of us is poor

now, Arthur;” and Sinclair had answered, hastily, “Yes, but I had better

make a place in the world for myself first—get established, you see,

dear. We don’t need to hurry. We have lots of time yet.”

Cleo had remained silent.

“When I am settled I will send for you to join me, dear,” Sinclair had

added, “if you are willing to come.”

“Willing!” she had answered, with indignant passion. “Oh, Arthur, I am

willing to go anywhere where you are.”

Her mother’s illness, soon after this, absorbed Cleo for a time, so that

when Sinclair left her, the date of their marriage still remained

unsettled.

That was three years before. Since then the girl had kept up an almost

constant correspondence with Sinclair. His letters were like him, tender

and loving, almost boyish in their tone of joyousness, for Sinclair

liked his new home and position so much that he wanted to remain there

altogether. He wrote to Cleo, asking if she would not now come to

41 Japan

and judge for them, and if she liked the country they would live there

altogether; if not—they would return to America.

The girl’s pride had long been roused in her, and but for her love for

Sinclair she might have given him up long before. But always the

overmastering love she had for him kept her waiting, waiting on for

him—waiting for him to send for her as he had promised he would. It is

true, she had grown used to his absence, and often tried to console

herself with the homage and love given by others, but it could not

be—her heart turned always back to the man she had loved from the

first, and even the little flirtations she indulged in were

half-hearted. Sometimes Sinclair’s letters showed a trace of haste and

carelessness, often they were almost cold and perfunctory. At such times

she would plunge into a round of reckless gayety, and try to forget for

the time being her unsatisfied longing and love. And now she was on her

way to join him. The voyage was long, and would have been tedious had it

not been for Takashima. He gave her a new interest. Most of the other

passengers she found uninteresting. Sinclair’s last letters, although

speaking of her trip, and seemingly urging her to come, appeared to her,

sometimes, almost forced. The girl’s proud, spoiled heart rebelled. It

was with a feeling as much of hunger for sympathy and love, as of

coquetry, that she had started her acquaintance with Takashima, and now

as she lay in the narrow little couch in her room, she was asking her

heart with a sudden fear whether her hunger for

42 love had overpowered

her. She was of a passionate, intense nature. It galled her always that

she was separated from the man she loved,—that she could not at once

have by her the love he had protested he felt for her. She buried her

face in the pillows and sobbed bitterly. With a passionate nervousness,

she thrust his picture away from her, and tried to think, instead, of

Takashima, the gentle young Japanese who now loved her—not as Sinclair

had done, with a passion of a moment that swept her from her feet, but

with deference and respect, and yet with as strong a love as she could

have desired.

CHAPTER IX. MERELY A WOMAN.

Even a woman in love can put behind her easily, for a time, the image of

the one she at heart loves, when she replaces it with one for whom she

cares (not, perhaps, in the same wild way as for the other, but with a

sentiment that is tantamount to a flickering, wavering love—a love of a

moment, a love awakened by gentle words—and perhaps put away from her

after she has reasoned it out to herself); for it is true that the best

cure for love is to try to love another.

Cleo Ballard was not heartless. She was merely a woman. That is why,

half an hour after she had wept so passionately, she was smiling at her

own beautiful face in the mirror, as she brushed her long wavy hair

before it.

She was thinking of Takashima, and of his love for her, which he could

not summon the courage to tell her of, and which she tried always to

prevent his doing. There was a stubborn, half pettish look on her face

when she thought of his possible love for “the Japanese girl.”

“Even if I cannot be anything to him,” she told herself, remorselessly,

“still, if he does not love her, I’m doing both a kindness in preventing

his marrying her.”

44

She paused in her toilet, and sat down a moment to think.

“I can’t analyze my own feelings,” she said, half-fretfully. “I don’t

see why I should feel so—so bad at the idea of his—his caring for any

one else. I am not in love with him. That is foolish. A woman cannot be

in love with two men at once.”

She smiled. “How strange! I believe it is true, though, and yet—and

yet—if it is so—how differently I care for them!”

She rose again, and commenced twisting her hair up.

“Oh, how provoking it is! I don’t believe there are many girls who would

admit it—and yet it is true—that we can love one man and be ‘in love’

with another.” She pushed the last pin into her hair impatiently. “I

believe if it were not for the fact that he—that he—might really care

for some one else—I’d give him up now, but somehow, as it is—Oh! how

selfish—how mean I am!” She stopped talking to herself, and opening the

door called out to her mother in the next room:

“Mother dear, are you dressing for dinner yet?”

The mother’s weak voice answered: “No, dear; I shall not be at the table

to-night.”

“Oh, mother, I want you with me to-night,” she said, regretfully, going

into her mother’s room.

“You want me with you?” said the mother, with mild astonishment. “Why,

my dear, I thought—you usually like being alone—or—or with

Mr.—er—with the Japanese.”

“Not to-night, mother—not to-night,” she said,

45 and put her head down

on her mother’s neck with a half-caress, a habit she had had when a

little girl, and which sometimes returned to her when in a loving mood.

“I don’t understand myself to-night, mother,” she whispered.

The peevish, nervous tones of the invalid mother repulsed her.

“My dear, do not ruffle my hair so—There! go on to the dining-room

like a good girl. And do, dear, be careful. I am so afraid of your

becoming too fond of this—this Japanese. You are always talking about

him now, and Tom says you are inseparable on deck.”

The girl raised her head, and rose from her kneeling posture beside her

mother. There was a cold glint in her eyes.

“Really, mother, you need not fear for me,” she said, coldly. “Tom only

says things for the sake of hearing himself talk—you ought to know

better than to mind him.”

“We are so near Japan now,” the mother said, peevishly, “and we have

waited three years. I am not strong enough to stand anything like—like

the breaking of your engagement now. My heart is quite set on Sinclair,

dear—you must not disappoint me.”

“Mother—I—,” the girl commenced, in a pained voice, but the mother

interrupted her to add, as she settled back in her pillows,

“There,

there, my dear, don’t fly out at me—I understand—I really can trust

you.” There was a touch of tenderness mingled

46 with the pride in the

last hard words:

“You always knew how to carry your heart, my dear.”

The girl remained silent for a moment, looking bitterly at her mother;

after awhile her face softened a trifle. She leaned over her once more

and kissed the faded face. “Mother, mother—you really are fond of me,

are you not?—let us be kinder to each other.”

47

CHAPTER X. “WATCHING THE NIGHT.”

It was quite a wistful, sad-faced girl who took her seat at the table,

and answered, half absently, the light jests of some of the passengers.

Tom’s sharp ears missed her usual merry tone. He glanced keenly at her,

as she sat beside him, eating her dinner in almost absolute silence.

“What’s up, Cleo?”

“Nothing, Tom.”

“Don’t fib, now. You are not in the habit of wearing such a countenance

for nothing.”

“I can’t help my countenance, Tom,” she rejoined, with just a suggestion

of a break in her voice.

Tom looked at her a moment in silence, and then delicately turned his

head away. After dinner he took her arm very affectionately, and they

strolled out on deck together.

Takashima was sitting alone, as they came out. He was waiting for Cleo,

as usual, and had been watching the door of the dining-room expectantly.

Tom drew her off in a different direction from where the Japanese was

sitting. For a short time they walked up and down the deck, neither of

them speaking a word. Then Tom broke the silence, saying carelessly, as

he lit a cigar:

“Mind my smoking, sis?”

48

“No, Tom,” the girl answered, looking at him gratefully. Instinctively

she felt the ready sympathy he always extended to her, often without

even knowing her trouble, and seldom asking for her confidence. When she

was worried or distressed about anything, Tom would take her very firmly

away from every one, and if she had anything to tell she usually told it

to him; for since they had been little girl and boy together Tom had

been the recipient of all her woes. When he was a little boy of twelve,

his father and mother both having died, Cleo’s father, his uncle, had

taken him into his family, and the two children had been brought up

together. After the death of his uncle he had stood to the mother and

Cleo as father, brother, and son in one, and they both became very

dependent on him. Once in a while when he was feeling exceptionally

loving to Cleo he would call her “little sis.” That night he did so very

lovingly.

“Feeling blue, little sis?” he asked.

“Yes, Tom.”

Tom cleared his throat. “Er—er—Takashima?”

“No, Tom—it is not he. It is mother.”

Tom stopped in his walk, and made a half-impatient exclamation.

“Oh, Tom, I do want to love her so much—but—but she won’t let me. I

mean—she is fond of me, and—and—proud, I suppose, but whenever I try

to get close to her she repulses me in some way. We ought to be a

comfort to each other, but—but there is scarcely any feeling between

us.” She caught her breath.

“Tom, I don’t know what’s the matter49 with

me to-night. I—I—Oh, Tom, I do want a little sympathy so much.”

The young man threw his lighted cigar away. He did not answer Cleo, but

he drew her little hand closer through his arm. After a time the girl

quieted down, and her voice had lost its restlessness when she said:

“Dear Tom—you are so good.”

They strolled slowly back in the moonlight to where Takashima was

sitting. He was leaning over the railing, watching the dark waves

beneath in their silvery, shimmering splendor, touched by the moon’s

rays. He turned as Tom called out to him:

“See a—a whale, Takie?”

“No; I was merely watching the—the night.”

Cleo raised her head and smiled at Tom, both of them enjoying the

Japanese’s naive way of answering.

“I was watching the night,” he repeated, “and thinking of Miss Cleo. We

generally enjoy such sights together.”

“Well, to-night I thought I had a lien on her for a change,” Tom said.

“Cleo is too popular to be monopolized by one person, you know.”

The Japanese smiled—a happy, confident smile. It touched the girl, and

she said, impetuously: “Tom, it always depends on who has the monopoly.”

Tom answered with mock sternness: “Very well, madam; I leave you and

Takie to the tender mercies of each other.”

“Your cousin likes you very much, does he not?” the Japanese asked her,

as Tom moved away.

50

“Yes; Tom is the best boy in the world. I don’t know what I’d do

without him.” She leaned her head against the railing. His next quiet,

meaning words startled her: “Would you wish to marry with him?” She

laughed outright; for she perceived the first touch of jealousy he had

shown in these words.

She lifted her little chin in its old saucy fashion.

“No—not if Tom was the only man in the world. It would be too much like

marrying one’s brother.”

She smiled at the anxious face of the Japanese. He bent over her chair a

moment, then he drew back and stood against the rail, in a still

indecisive posture. The girl knew instinctively what he wanted to say.

Perhaps it was because she was tired, and her heart was hungry for a

little love, that she did not try to prevent him from speaking.

“This afternoon, Miss Ballard, your words gave me courage. Will you

marry with me?” he asked.

The question was so direct she could not evade it. She must face it out

now. Yet she could find no words to answer at first. The effort it had

cost the Japanese to say this had made him constrained, for he had all

the pride of a Japanese gentleman; and after all he was not so sure that

the girl would accept him. He had been told it was customary in America

to speak to the girl herself before speaking to the parents, and it was

in a stiff, ceremonious way that he did so. He waited silently for her

answer.

“Don’t let us talk about—about such things,” she said; and again there

was that little break in her voice that had been there when Tom had

walked with her.

“Our—our friendship has been so51 delightful,” she

added;

“don’t let us break it just now.”

For the first time since she had known him there was a note of sternness

in Takashima’s voice.

“Love should not break friendship,” he said. “It should rather cement

it.”

The wind blew her hair wildly about her face, and in her restlessness it

irritated her. She put her hands up and held back the light, soft curls

that had escaped.

“Shall I speak to your mother?” he asked her.

“No!—No!” she said, quickly; “mother has—has nothing to do with it.”

“Will you not tell me what to expect, then?” The sadness of his voice

touched the girl’s heart, bringing the tears to her eyes.

“I cannot answer yet. Wait till we get to Japan. Please wait till then.”

“I tried to plan ahead,” he said, “but you are right, Miss Ballard. You

will want some time to think this over. It will be but five days now

before we reach Japan. If that you are very kind to me in those five

days my heart shall take great hope of what your answer will be.”

52

CHAPTER XI. AT THE JOURNEY’S END.

Cleo Ballard could not have told what it was that made her so restless,

almost feverish, during those remaining five days. She knew Takashima

had meant to ask her to show in some way, during that time, just what he

might expect. It was almost a prayer to her to spare him, if she knew it

was in vain. But the girl was possessed, during those days, with an

almost feverish longing for his companionship and sympathy. She showed

it constantly when with him; she would look unspeakable longings into

his eyes, longings she could not understand or analyze herself; she led

him on to talk of his plans, and he even told her of some wherein he had

counted on her companionship—how he would have a Japanese-American

house—a home wherein both the beauty of Japan and the comfort of

America would be combined; and of the trips they would take to Europe,

and the friends they would make. He used the word “we” always, in

speaking, and she never once questioned his right to do so. Often she

herself grew so interested in his plans for the future that she made

suggestions, and they laughed with light-hearted joyousness at the

prospect. At the end of the five days Takashima had not even a lingering

doubt left.

As the shores of his home came into view, and the

53 passengers were all

clustered on deck watching the speck of land in the offing grow larger

and larger as they approached it, the young Japanese placed his hand

firmly on Cleo’s—so soft and slender—and said:

“Soon we will reach

home now—your home and mine.”A sudden vague fear crept into the girl’s heart. She shivered as his

hand touched hers, and there was a frightened, almost hunted, look in

her eyes.

“Shall I have my answer now?” he continued.

Again she shivered. “Wait till we are on shore,” she pleaded, “till we

have rested; wait five more days—I must think—I—I——”

“Ah, Miss Cleo, yes, I will wait,” he said, gently. “Surely, I can

afford to do so. It is after all merely the formal answer I will ask

for. These last days you have already answered me—with your beautiful

eyes.”

“Tom,” the girl said, desperately, as the passengers were passing from

the boat on to the dock below, and her cousin was tying the heavy straps

around their loose baggage, “Oh, Tom—I am afraid now—I am afraid

of—of Takashima.”

Tom’s usually sympathetic face was almost stern. He rose stiffly and

looked at the girl remorselessly.

“I warned you, Cleo,” he said; “I told you to be careful. You ought to

have answered him directly five days ago, when he spoke to you. You are

the greatest moral coward I know. I believe you could not summon pluck

enough to refuse anybody. Don’t know how you ever did. It is a wonder

you are not engaged to a dozen at once.”

54

CHAPTER XII. THOSE QUEER JAPANESE!

Kyoto is by far the most picturesque city in Japan. It is situated

between two mountains, with a beautiful river flowing through it. It is

connected with Tokyo by rail, but the traveling accommodations are far

from being as comfortable or commodious as in America; in fact, there

are no sleeping-cars whatever, so that it is often matter of complaint

among visitors that they are not as comfortable traveling by rail as

they might be. It was in Kyoto that Sinclair and most of the Americans

who visited Japan lived. Sinclair kept one office in Kyoto and another

in Tokyo, and being inclined to shove most of his light duties on to his

secretary, went back and forth between the two cities; in fact, he had a

house in both places. Tokyo, with its immense population and its air of

business and activity, is yet not so favored by foreigners, nor by the

better class Japanese, as a place of residence as is Kyoto. Indeed, a

great many of them carry on a business in Tokyo and also keep a house in

Kyoto. Most of the merchants of Tokyo, however, prefer to live in one of

the charming little villages a few hours’ ride by train from Tokyo, on

the shores of the Hayama, where there is a good view of Fuji-Yama, the

peerless mountain. And it was almost

55 under the shadow of this mountain

that Takashima Orito and Numè had played together as children.

The Ballards took up their residence for the time being in the city of

Tokyo, at an American hotel, where most of the other passengers who had

arrived with them were staying. Arthur Sinclair had failed to meet them

at the boat, though he sent in his place his Japanese secretary, who

looked after their luggage for them, hailed jinrikishas, and saw them

comfortably settled at the hotel, apologizing profusely for the

non-appearance of Sinclair, and explaining that he had gone up to Kyoto

the previous day, and had been delayed on important business.

When they were alone in their rooms the mother sank in a chair,

complaining bitterly that Sinclair had failed to meet them.

“I will never get used to this—this strange place,” she said, with her

chronic dissatisfaction. “I won’t be able to stay a week here. How could

Arthur Sinclair have acted so outrageously? I shall tell him just how I

feel about it.”

“Mother,” Cleo turned on her almost fiercely, “you will say nothing to

him. If he had something more important to attend to—if he did not want

to come—we do not want him to put himself out for us—we do not care if

he does not.” Her voice reflected her mother’s bitterness, however, and

belied her words.

“He was always thoughtful,” said Tom, laying his hand consolingly on his

aunt’s shoulder.

“Come now, Aunt Beth, everything looks comfortable

here56—and I’m sure after we once get over the oddity of our

surroundings we will find it quite interesting.”

“It is interesting, Tom,” said Cleo, from a window, “the streets are

so funny outside. They are narrow as anything, and there are signboards

everywhere.”

Mrs. Ballard looked helplessly about the room.

“Tom, what do you suppose they will give us to eat? I have heard such

funny tales about their queer cooking—chicken cooked in molasses,

and—and raw fish—and——”

“Mother,” put in the girl, impatiently, “this hotel is on the American

plan. The little bell-boys and servants, of course, are Japanese—but

everything will be as much like what we have at home as they can make

it.”

Both the mother and daughter were out of patience with everything and

were tired, the mother being almost hysterical. Tom went over to her and

tried to calm her down, talking in his easy, consoling way on every

subject that would take her mind off Sinclair. After a time Mrs.

Ballard’s nervousness had quieted down, and she rested, her maid sitting

beside her fanning her gently, while Tom and Cleo unpacked what luggage

they had had in their staterooms with them, their other trunks not

having arrived. The girl was feeling more cheerful.

“When I go back to America,” she said, “I believe I’ll take a little

Japanese maid with me. They are so neat and amusing.”

Tom looked at her gravely. “I thought you contemplated making your home

here?” he quizzed.

57

“Perhaps I will,” the girl said, saucily, “perhaps I won’t. It depends

on whether my mind changes itself.”

“Hum!”

“Remember Jenny Davis, Tom?”

“Well, I guess so;—never saw you alone when she was in Washington.”

“Well, she brought home with her the sweetest little Japanese maid you

ever saw. She used to be—a—a geesa girl in Tokyo, and the people she

worked for were horrid to her. So Jenny paid them some money and they

let her bring—a—Fuka with her to America. Well, I wish you could have

seen her. She wasn’t bigger than that, Tom,” measuring with her hand,

“and she was just as cute as anything,—walks on her heels, and smiles

at you even when you are offended with her, Jenny says.”

“Where is Mrs. Davis now?” Tom asked. “Thought I heard some one say she

had come back here.”

“So she did. She is somewhere in Japan now. Last time I heard from her

she was in Kyoto. I wrote her, care of Arthur though, because she moves

around so much, and I told her we were coming. I half expected she would

meet us.” After thinking a moment she added,

“Tom, do you know, there

was not a single American to meet us? I think mamma is right (though I

won’t tell her so), and that Arthur acted abominably in not meeting us.

It doesn’t matter what business he had—he should have left it. He

might at least have sent—a—a friend to meet us, instead of that

smooth58 Japanese. Mrs. Davis says there is a perfect American colony

here, and in Yokohama and Kyoto—they are scattered everywhere, and

Arthur knows them all, and most of them know we are to be married.”

“Sinclair’s hands, I guess, are pretty full most of the time. Every

American nearly that comes here pounces onto him. He wrote me once that

he had a different party to dinner nearly every day at the

Consulate—when he is in Kyoto, and I guess that is why the poor chap

likes to run down here where every tourist does not throw himself at

him. Sinclair never was a good—a—business man. Don’t believe he has

any idea of the responsibility of his work. Believe he’d just as lief

throw it up, anyhow.”

But, though Tom stood up for his friend, even he could not help feeling

in himself that the girl was justly indignant.

59

CHAPTER XIII. TAKASHIMA’S HOME-COMING.

Takashima had left the Americans at the dock. He had offered the

Ballards every courtesy, even inviting them to go with him to his home.

This, however, they refused, and as it had been so long since he had

been in Japan he was almost as much a stranger to his surroundings as

they were; so he left them to the care of Sinclair’s secretary, feeling

confident that he would show them every attention,—telling them that he

would call on them the next day. He realized that they felt a trifle

strange, and wanted, in his generous, gentle way, to make them feel at

home in Japan. Two old Japanese gentlemen who stood on the dock, peering

eagerly among the passengers as they passed down the gangway, now paused

before him. Both were visibly affected, and the one who called his name

so gently and proudly trembled while he did so.

“Orito, my son.”

“My father,” the young man answered, speaking, impulsively, in pure

Japanese. With one old man holding each of his arms he moved away. Cleo

looked after them, her beautiful eyes full of tears.

“It is his father,” she had said. “They have not seen each other for

eight years.” Her voice faltered a trifle. “The other one must be her father.”

60

CHAPTER XIV. AFTER EIGHT YEARS.

It was with mingled feelings of pleasure and, perhaps, pain that

Takashima Orito saw his home once more. The place had scarcely changed

since he had left it eight years before. It seemed to him but a day

since he and Numè had played on the shores of the Hayama, and had

gathered the pebbles and shells on the beach. He remembered how Numè

would follow him round wherever he went, how implicitly she believed in

him. Surely, if he lived to be a hundred years old never would such

confidence be placed in him again—the sweet, unquestioning confidence

of a little child. After dinner Orito left his father and Omi to go

outside the house and once more take a look at the old familiar scenes

of his boyhood; once more to see Fuji-Yama, the wonderful mountain that

he had known from his boyhood, and of which he had never tired. There it

stood in its matchless lonely peace and splendor, its lofty peaks

meeting the rosy beams of the vivid sky, snow-clad and majestic. Ah! the

same weird influence, the same inexplicable feeling it had always

produced in him had come back now, and filled his soul with an ardent,

yearning adoration. Every nerve in the young man bespoke a passionate

artistic temperament. Many a time when in Amer-

61ica, wearied with

studying a strange people, strange customs, and a strange God, his mind

had reverted to Fuji-Yama—Fuji-Yama, the mount of peace, and in his

heart would rise an uncontrollable longing to see it once more, for it

is said that no one who is born within sight of Fuji-Yama ever forgets

it. Though he might roam all the world over, his footsteps inevitably

turn back to this spot. Standing majestically in the central part of the

main island, snow-clad and solitary, surrounded by five lakes, it rises

to the sublime altitude of 12,490 feet. It is said that its influence is

almost weird—that those who gaze on it once must always remember it.

They are struck not so much by its grandeur as by its wonderful

simplicity and symmetry. It is suggestive of all the gentler qualities;

it is symbolic of love, peace, and restfulness.

Orito remained outside the house for some time, his face turned in mute

adoration to the peerless mountain, no sound escaping his lips. When his

father joined him he said, with a sigh: “Father, how came I ever to

leave my home?”

The old man beamed on him, and leaned against his shoulder.