“Please to welcome to my house!”

The words and the voice, with its fascinating accent, took me back, in thought at least, to a country far across the sea. I should have been entering a little house with a deep blue or pink roof, with sliding walls of paper shoji, wide spaces of shining matting, soft tatamis on which to kneel. My hostess would be serving me tea in a tiny handleless cup, and perhaps there would be a sweetmeat or fruit on my plate, perhaps a little omelet formed in the shape of a blossom. We would sit on the floor and sip our tea and discuss the flower decoration in the slender vase or the history of the kakemona scroll in the Tokonoma (Place of Honor).

But no! I was not in Japan. I was entering a very ordinary little American house. At the door, smiling and bowing, were Mr. And Mrs. Sojin Kamiyama.

1

Doug Grabbed Him

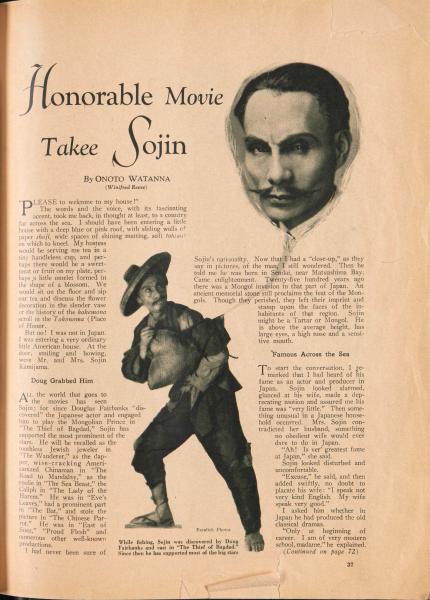

All the world that goes to the movies has seen Sojin; for since Douglas Fairbanks “discovered” the Japanese actor and engaged him to play the Mongolian Prince in “The Thief of Bagdad,” Sojin has supported the most prominent of the stars. He will be recalled as the toothless Jewish jeweler in “The Wanderer,” as the dapper, wise-cracking Americanized Chinaman in “The Road to Mandalay,” as the coolie in “The Sea Beast,” the Caliph in “The Lady of the Harem.” He was in “Eve’s Leaves,” had a prominent part in “The Bat,” and stole the picture in “The Chinese Parrot.” He was in “East of Suez,” “Proud Flesh” and numerous other well-known productions.

I had never been sure of Sojin’s nationality. Now that I had a “close-up,” as they say in pictures, of the man, I still wondered. Then he told me he was born in Sendai, near Matsushima Bay. Came enlightenment. Twenty-five hundred years ago there was a Mongol invasion in that part of Japan. An ancient memorial stone still proclaims the feat of the Mongols. Though they perished, they left their imprint and stamp upon the faces of the inhabitants of that region. Sojin might be a Tartar or Mongol. He is above the average height, has large eyes, a high nose and a sensitive mouth.

Famous Across the Sea

To start the conversation, I remarked that I had heard of his fame as an actor and producer in Japan. Sojin looked alarmed, glanced at his wife, made a deprecating motion and assured me his fame was “very little.” Then something unusual in a Japanese household occurred. Mrs. Sojin contradicted her husband, something no obedient wife would ever dare to do in Japan.

“Ah! Is ver’ greatest fame at Japan,” she said.

Sojin looked disturbed and uncomfortable.

“Excuse,” he said, and then added swiftly, no doubt to placate his wife: “I speak not very kind English. My wife speak very good.”

I asked him whether in Japan he had produced the old classical dramas.

“Only at beginning of career. I am of very modern school, madame,” he explained.

72

His wife put in eagerly: “My husband first pioneer in new drama movement—Little theater, you understand. He make first production in Shakespeare, Ibsen, Sudermann, Goethe— many other—one hundred other!”

I tried to imagine a Japanese audience watching a performance of “The Doll’s House,” “The Master Builder,” “Hedda Gabler,” “The Merchant of Venice,” “Hamlet,” “Othello,” “Anthony and Cleopatra,” “Faust,” and the Russian, German, and French plays, all of which were included in Sojin’s repertory.

“Were these European plays successful?”

“Very so,” said Sojin. Again Mrs. Sojin interposed, eagerly: “Always plenty people come to theater. High class people—intelligentsia—artist, writer, student, scholar. All very hungry see my husband in European drama.”

He Knew His Foreigners

Sojin here explained the really monumental task achieved in studying and producing these plays in Japan. There would be foreign companies touring there, and playing in the chief cities. He would go to every performance, intensively study the plays and the style of the acting. He was, moreover, a pupil of Professor Tsubuchi, at Waseda University, the scholar who translated into Japanese not only Shakespeare, but Ibsen and the Russian, German, and French classics.

Sojin explained that he produced some of these plays as Japanese. That is to say, he would transpose the originals and adapt them so that the scene was Japan and the characters Japanese. Thus Hamlet became Prince Hamura Tashimura, son of the reigning Daimyo (Lord or Prince) of a great feudal Province. Othello was a new-rich Prince, of Pariah ancestry, as he was descended from the despised Eta race. Desdemona was a Princess of high Patrician blood. “King Lear” was a favorite with the Japanese. Sojin was inclined to think that the plays of Shakespeare bore a resemblance to many of the old Japanese classics.

The stage is a subject near to the heart of Sojin, but I presently brought the subject around to motion pictures.

“Are the movies popular in Japan? Do the Japanese like American pictures?”

Sojin is slow at replying. He weighs a question and sorts out his words. Then he answers with something of a flash as if the answer had just occurred to him.

“Ah! How like movie at Japan? Very much same as American first like chop suey. You understand?”

We laugh in complete understanding, but Mrs. Sojin puts in almost breathlessly: “It is give shock, very strange, queer, liddle bit suspicious, but very much like little while.”

Sojin who has come somewhat out of his shell by now, likens the movie craze in Japan to an epidemic. Everybody goes to the movies. The favorite stars are Charlie Chaplin, Lillian Gish, Nazimova, Fairbanks and Hoot Gibson.

“How do Japanese audiences react to the sex element in American pictures?” I ask.

Sojin considers. He has recourse to his wife. They whisper a bit in Japanese, and then Mrs. Sojin in English: “Sex—it is American make—Love—kiss—embrace.” She illustrates, quite eloquently, with her hands. Sojin nods and blinks with dazed comprehension. Then she continues:

“Well, Japanese audience get one shock after one another on American play. He’s adjust to new kind shock. He is shock, struck, kick, shooted at. All very different Japanese ideal. Very much bewilder and delicious fright.”

A pause, thoughtful on Sojin’s part. Then leaning forward, with his long sensitive hands flattened together, he says: “Very significant thing I confide you. Three year ago ninety per cent. Japanese people want foreign picture. Ten per cent. ask Japanese picture. Today he is changing. Eight per cent. Japanese people ask for Japanese picture. Twenty per cent. demand foreign.”

Mrs. Sojin deprecates this revelation.

“You understand. Americans not like see all pictures of Japanese or Chinese life maybe. Is same at Japan. You understand? Sank you!”

Hard Times in Filmdom

It is a pleasure, it is delightful to hear Mrs. Sojin’s naïve and quaint speech. She has a most engaging smile and her slightly high cheek bones are flushed rosily. It is she who is careful to get in the information anent her husband’s ancestry and education. His family were samurai under the Princes of Date. His father was a scholar. Sojin was graduated at Waseda University. Also he learned “the arts of picture” at the Tokyo Fine Arts School. It is worth while quoting Mrs. Sojin verbatim:

“My husband meditate deep on dramatic literature. He forerun movement of young Japan. He is leader, pioneer of new movement. He produce one hundred classical and modern European plays. The name of young Sojin spreaded whole country. He influence world of new thought. Meanwhile he also write two novels which make him an excellent author. About six year ago he leave Japan abruptly. We arrive Los Angeles to study motion picture. In vain find any way into movie. So we leave abruptly and travel over snowland of Canada where we see fine auroras.”

“We come back and make little magazine. It is call ‘East and West.’ This be to make Japanese understand and be friend to America. My husband create motto: ‘Super Americanization’ and he teach America always friend Japan. Meanwhile he cultivate his soul by fishing among mountain and seashore. One day at San Pedro, where he angle for tunnies, he meets with ‘Thief of Bagdad’ company. It was then he is found out by Douglas Fairbanks for Mongolian Prince. That’s begin. Now every company like to have him play some part no one play so well as my husband.”

The Thunder Is All His

Mrs. Sojin’s apple-red cheeks are as bright as her eyes, which are kindling with devotion and fervor. Not once has she mentioned the fact that she herself was a famous star in Japan, and she has delicately avoided mention of the love affair that developed between her husband and his charming leading lady, now Mrs. Sojin Kamiyama. Sojin is inclined to be diffident. He has that rare quality possessed by a true artist—modesty.

Before I leave I put a last question:

“Mr. Sojin, do you think Japan and America will ever be at war?”

Sojin’s eyes dilate indignantly. Then “Impossible! Japan cherishes intelligence. What for would she destroy what she has built? It is for interest both America and Japan be friends.”

We say good-bye in Japanese.

“Sayonara.”

“Sayonara. Happy dreams.”

Mrs. Sojin runs down the terrace after me. She puts a package in my hand. A little souvenir of Japan. I look back at little Mrs. Sojin, and in the language of the movies, the scene “lap dissolves” out and into Sojin and his wife in Japanese costume. The terraces are lined with plum trees in spring blossom and the house on the hill “fades” into the outlines of a pagoda. I can hear the wind bells tinkling in a faint breeze.