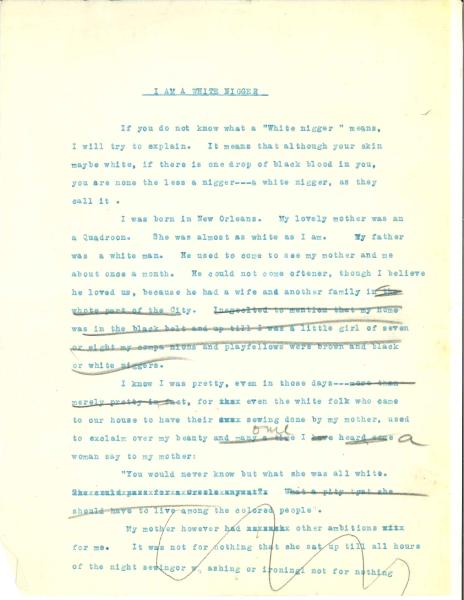

I am a White Nigger 1

If you do not know what a “White nigger” means, I will try to explain. It means that although your skin may be white, if there is one drop of black blood in you, you are nonetheless a nigger---a white nigger, as they call it.

I was born in New Orleans. My lovely mother was

a Quadroon.

2 She was almost as white as I am. My father was a white man. He used to come to see my mother and me about once a month. He could not come oftener, though I believe he loved us. Because he had a wife and another family in the

white part of the City.

I neglected to mention that my home was in the black belt and up till I was a little girl of seven or eight my companions and playfellows were brown and black or white niggers

3 I know I was pretty, even in those days, for even the white folk who came to our house to have their sewing done by my mother, used to exclaim over my beauty and once I heard a woman say to my mother:

“You would never know but what she was all white.”

2

“It seems a pity that she should have to live among colored people.”

My mother

did not reply, but that night she went on some special journey to the white part of the city, and when she came back a thin, middle aged woman was with her. My mother introduced her to me as my Tante Marie, and it seems she was a sister of my father, who was a Creole.

4 Most people think that the word

“Creole” implies colored blood, but that is not so. It means the very cream of old French and Spanish blood, without a taint of black to despoil it. My Creole aunt examined me with great and detached interest, holding up her

glasses to her nose, and studying me as if I were under a magnifying glass. Then, in French, which I could speak quite well, as most New Orleans children can, she said:

“Remarkable!”

For a long time after that she and my mother spoke in whispers. My mother’s face was flushed. She seemed to be pleading for something and her great dark eyes were moist with undropped tears. My aunt kept saying:

“It’s a risk. It would be a crime! No I will not be a party to it! Perhaps no one would ever find out----but the price would be paid in the next generation----of the next.”

Then my mother said:

“But there need be no other generation. It can stop with Fleur. I beg you to take 3 her with you. Give her her chance to be----a white girl.”

My aunt shook her head slowly, and my poor mother continued:

“She is white---all white---as white as any of the high and mighty LaTouches. Then let her be brought up a white girl.”

I saw my aunt looking at my mother very gravely and then she said:

“What of you, Madame? Do you care so little for your child that you are willing to give her up like this.”

My mother flamed back:

“You forget” said she, “that my ancestors were slaves. Our women saw their daughters taken from them and sold on the block like cattle to strangers--brutes and beasts. If my grandparents could do that, can I not be stoic enough to send my child to a place where I know her life’s happiness will be found.”

“I am not so sure of the happiness” said my aunt drily, “but I will think it over.”

Think it over she did, and within a few days after that conversation, I found myself on a train, with my aunt bound for the City of Chicago. Of course, I was too distracted and heartbroken at the time to know or or comprehend just where I was going. All I knew was that I was being taken from my adored mother. Perhaps I would never see her again. Perhaps I would never see my little brown and black and nigger white playmates. I sat crouched in a corner of the seat, sobbing my heart out.

4

My aunt said:

“You must stop crying. You must not abandon yourself to grief in that uncivilised fashion. You are now a white girl.”

“I’m not” I retorted wildly. “I hate white people.”

My aunt said coldly:

“You will lower your voice, if you please, when you address me. Anyone on the train might hear you.”

“I don’t care if they do” I sobbed tempestuously. “I hate, I hate, I hate all white people.”

“Then” said my aunt “if you do not obey me I shall be obliged to punish you.”

I flashed back scornfully:

“You can’t ---on the train The people won’t let you beat me.”

I am going to pass over the several years of my life spent in Chicago. My aunt was not a rich woman, but we had a nice little flat near the park. I went to school where, unlike New Orleans, there were both white and black children. They took it for granted that I was white, and as time passed I almost forgot myself that there was even that one drop taint in my blood. From time to time letters came from my mother, always with money enclosed. Not very much money, for I believe she

5 worked very hard to earn the money to support me, for it seems that although my father’s people were aristocrats, they were not at all rich, and my father who had

disapproved of the entire venture had broke off entirely with my mother after my departure. I believe he wrote Tante Marie on two or three occasions

declaring she had done and was doing an

outrageous thing, and that the imposture was sure eventually to be discovered. If she would not bring me back, he would

wash his hands of the entire matter. My aunt replied, for so

she cooly informed me, that she would only bring me back when I had disproved my right to be a white girl. It all depended on my conduct.

So time passed of course, I had no desire whatsoever to return. I acquired a sort of snobbish aversion for colored people, and I always avoided contact with them.

When I was seventeen years old, as we were in very poor circumstances and my mother’s remittances had become smaller and rarer, I had to go to work. I got a job at a newstands in the Ambassador hotel. I think Tante Marie felt very badly about my having to work at so young an age, and she made me keep at my music and French lessons, for she always hammered into me the fact that culture was everything, and if I could maintain an atmosphere of refinement, I would be welcome anywhere. Also, in her proud moments, she would remind me that I must not forget that no matter who my mother was, on my father’s side I was a LaRocque.