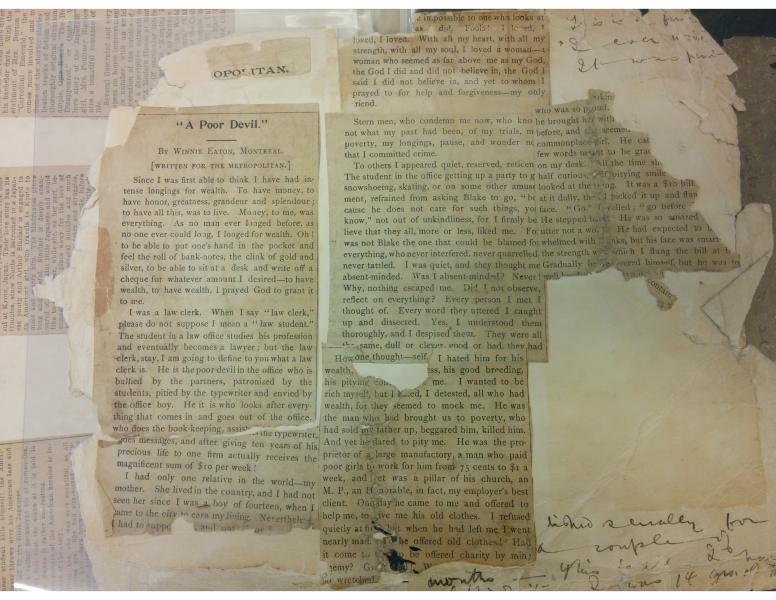

Since I was first able to think I have had intense longings for wealth. To have money, to have honor, greatness, grandeur and splendour; to have this, was to live. Money, to me, was everything. As no man ever longed before, as no one ever could long, I longed for wealth. Oh! to be able to put one’s hand in the pocket and feel the roll of bank-notes, the clink of gold and silver, to be able to sit at a desk and write off a cheque for whatever amount I desired—to have wealth, to have wealth, I prayed God to grant it to me.

I was a law clerk. When I say “law clerk,” please do not suppose I mean a “law student.” The student in a law office studies his profession and eventually becomes a lawyer; but the law clerk, stay, I am going to define to you what a law clerk is. He is the poor devil in the office who is bullied by the partners, patronized by the students, pitied by the typewriter and envied by the office boy. He it is who looks after everything that comes in and goes out of the office, who does the book-keeping, assists the typewriter, gives messages, and after giving ten years of his precious life to one firm actually receives the magnificent sum of $10 per week!

I had only one relative in the world—my mother. She lived in the country, and I had not seen her since I was a boy of fourteen, when I came to the city to earn my living. Nevertheless, I had to support her, and out of my $

impossible to one who looks at the world as I did. Fools! I loved, I loved, I loved. With all my heart, with all my strength, with all my soul, I loved a woman—a woman who seemed as far above me as my God, the God I did and did not believe in, the God I said I did not believe in, and yet to whom I prayed to for help and forgiveness—my only friend.

Stern men, who condemn me now, who know not what my past had been, of my trials, my poverty, my longings, pause and wonder not that I committed crime.

To others I appeared quiet, reserved, reticent. The student in the office getting up a party to go snowshoeing, skating, or on some other amusement, refrained from asking Blake to go, “because he does not care for such things, you know,” not out of unkindliness, for I firmly believe that they all, more or less, liked me. For was not Blake the one that could be blamed for everything, who never interfered, never quarrelled, never tattled. I was quiet, and they thought me absent-minded. Was I absent-minded? Never! Why, nothing escaped me. Did I not observe, reflect on everything? Every person I met I thought of. Every word they uttered I caught up and dissected. Yes, I understood them thoroughly, and I despised them. They were all the same, dull or clever, good or bad, they had one thought—self.

How I hated him for his wealth, ess, his good breeding, his pitying con me. I wanted to be rich myself, but I hated, I detested, all who had wealth, for they seemed to mock me. He was the man who had brought us to poverty, who had sold my father up, beggared him, killed him. And yet he dared to pity me. He was the proprietor of a large manufactory, a man who paid poor girls to work for him from 75 cents to $1 a week, and yet was a pillar of his church, an M. P., an Honorable, in fact, my employer’s best client. One day he came to me and offered to help me, to give me his old clothes. I refused quietly at first but when he had left me I went nearly mad. To be offered old clothes! Had it come to this to be offered charity by mine enemy? Great God! W so wretched

who was so proud. he brought her with him before, and she seemed a commonplace girl. He few words meant to be on my desk. All the time she half curious, if pitying smile looked at the thing. It was a $10 bill. I looked at it dully, then I picked it up and flung it in his face. “Go,” I yelled; “go before I.” He stepped back. He was so amazed he uttered not a word. He had expected to be overwhelmed with thanks, but his face was smarting from the strength with which I flung the bill at him. Gradually he recovered himself, but he was too well bred