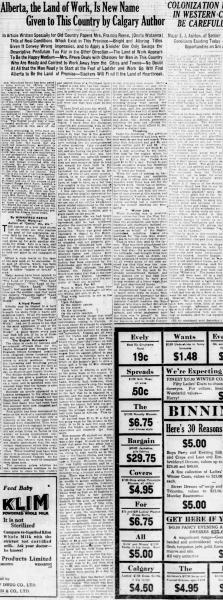

Mrs Winnifred Reeve has been asked to write articles for certain British newspapers and for the London Board of Trade, dealing with “ranching, farming, trapping, and anything else in which the surplus population of England might turn for a living if carried over to Canada.” Special Inquiry into the matter of the 12,000 harvesters who came to Canada during the last year is requested. Stress was laid upon the fact that Great Britain’s trouble today is unemployment. “Dominion statesmen are anxious to help by taking consignments of the unemployed people and settling them in their respective countries. The English people wish a clear unbiased statement of conditions as they exist now in this part of the world.”

Before attempting to write such articles,

Mrs. Reeve stated that she would have to satisfy herself that conditions were such that it would be desirable to induce people from the Old Country to come out here. She stated that she could not conscientiously contribute to anything that might be termed propaganda, unless she was assured that we could take care of and give employment to our prospective future children. She has made an exhaustive study of the matter and has interviewed numerous men and women connected with the railroads, the government, the soldier settlement board, and she has talked with many of the men themselves both in the city and in the country. This article is the result of her investigations.

Mrs. Reeves, besides being an author is also a rancher and farmer. She is secretary and one of the owners of the Pleasant Range Stock Farm, Limited, a cattle ranching corporation, and the Rocky View Farms, Limited, a grain ranching company, of which her husband is president. For the past seven years

Mrs. Reeve has lived on the farms and ranches of these companies, and she has come in personal contact with all types of farm hands and laborers. She knows the point of view of both the farmer and the farm hand, and she is well acquainted with the conditions that prevail upon the Alberta farms today.

Author of Cattle, etc., etc.

The history of a new land shows that for every one who reaches the goal of his aspirations, another falls by the way. That is life; that is human nature. What one man picks up for gold, another discards for dross. Life is a race, and not all of us may win the first of the prizes; but, at least we all may strive to hold our place in the vanguard of life.

Either a man reacts to the spur of the new land, or he succumbs. It is said of Alberta, which has been called “The Last of the Big Lands,” that it either “makes or breaks” a man.

Many names have been applied to this great province: “Sunny Alberta,” “The Land of Promise,” “The Land of Opportunity,” “The Land of Optimism,” “Man’s Land,” “God’s Land”; but opposed to these bright titles are the sinister ones that name the country “Vampire Land,” “Land of Heartbreak,” “Land of Lost Hopes.”

A Hard Parent

Alberta may be likened to a hard parent, who nevertheless conceals beneath his stern front a warm and generous heart. Of all the names applied to it, I do not recall ever hearing Alberta named as “The Land of Work.” And yet it seems to me that is the most applicable of any of the titles for Alberta--“The Land of Work.” A place where every man may find his job, if he is of those who are willing and able to work.

The English Harvesters

The claim is made by railroad and government officials that for the twelve thousand men brought from England, fifteen thousand positions were obtained—three thousand more positions than there were men. This refers to winter positions. During the harvesting and threshing period these men were put upon the land at the going wage of from $4 to $6 a day as stookers and bundle throwers.

The Soldier Settlement Board claim that they can give a position today to any man who is willing to work on a farm, and is satisfied with the nominal wage that the farmer is able to afford for winter work.

Recently an article appeared in a London newspaper to the effect that there was no work in Canada for the Englishmen, and warning those at home that many who had come here this summer were now stranded and in desperate straits.

This article has been denounced by some as the work of a malcontent and agitator. It is claimed that only a minority of the men who came from England were dissatisfied. They were men who had been engaged in various trades in the cities at home, and they did not relish living on farms in the winter, or taking employment outside the cities. It was a mistake to bring to this country men who did not clearly understand that the only certain employment which this country can proffer is that outside of the cities. Three hundred men have been placed in positions upon the farms in the district around Calgary. So far there has been no word of complaint from these men.

The question arises whether we can conscientiously continue to induce men to come to this country and assure them of a livelihood here. I asked a man who has had considerable to do with the placing of the men in positions just what the prospects were of future employment for such men and he replied with intense seriousness, and as if the subject were one that was close to his heart:

“l have lived all over the world. I have made a special study of labor conditions wherever I have been. I know how things are at the present day on the farms in the United States. I know what the European countries are contending with in the way of unemployment. I can truthfully say to you, because I honestly believe it, that this is the greatest country in the world for the man who comes here determined to work. We have nothing like the unemployment of other countries. Like everywhere else in the world, our farmers have felt, and are feeling the pinch of hard times, following the war, but, like the land itself, our splendid farmers are of a recuperative nature, and they are sure sooner or later to reap the reward for their faith in the land. Look at this last year. We harvested the greatest crop in the history of this or any other country. Alberta is on the upward climb of the ladder. I’d stake everything I have, or hope to have, on a bet that this country is due to become one of the greatest countries in the world.”

I was especially interested in the problem of the English harvesters because we ourselves employed several of them upon our grain farm, and we are one of the outfits which have given winter employment to the men from the old country. We operate a cattle ranch in the foothills, and a grain ranch on the prairie.

Like everyone else we had heard the hard luck tales of certain of the harvesters, and we had wondered whether the complaints would prove as in the case of the Hebrideans, premature. There was great alarm expressed in regard to the Hebrideans when they first came here, and it was predicted that they would be stranded and not properly provided for. I understand now that after the first confusion of placing them upon the land had passed, satisfactory farms and homes were found for them all, and none of them now desire to return. General satisfaction has been expressed by the Hebrideans, and their future looks promising. The railroads, the government, the Soldier Settlement Board now insist that this is the case also with the English harvesters. They were well treated, and the majority of them are satisfied.

Work For All

There is work, declare those who are in a position to know, for all who are willing and able to do it.

That work, however, is not in the cities, but:

- Upon the land;

- In the lumber camps;

- In the mines;

- In the railroads;

- On the cattle ranches.

There are several things that must be borne in mind by the men who contemplate coming to Canada. It is most unfair to attempt to organise farm laborers into a sort of a union, as was done this summer by some of the harvesters. Unions are all very well for trades and other forms of labor. In a new country like this, where every man—the farmer as well as his “hand”—is himself a laborer, to hold the hard worked and harassed farmer at harvest time for wages that he cannot afford to pay and continue to function save at a loss, is a poor return for a sincere effort on the farmer’s part to give a home and a living to the stranger within his gates.

Farm labor in Alberta is paid for at the going wage of the season. If there is a good crop in sight, wages soar accordingly. If, on the other hand, drought, hail, cutworm, frost wipe out the farmer’s crop, the wages must necessarily be low. This is not the fault of the farmer, but is due to the fact that he is engaged in a gamble, and the man who works for him must take his chance with the farmer who has speculated not merely with his money, but with his personal labor; $30 to $60 a month is today the average wage of the general farm hand in Alberta. This includes board.

At harvest time $3 to $5 a day is the going wage for the stooker in the field; $4 to $6 is paid the man who rides the binder, as more skill and experience are required for that work.

This summer we started our stookers at $4 per day and board. This was a fair wage. It must be borne in mind that since the war, grain has a low value. A great part of the world’s markets have been closed to us, owing to high tariffs as in the case of the United States, and bankruptcy and inability to buy in the case of Europe. However, this country was highly optimistic and in a happy state of mind when the harvest set in. In the first place we had an immense crop, a bumper and a record crop. There was work for everyone. Indeed, it was feared that we would be unable to secure sufficient labor for the harvest. Despite, however, the bumper crop—and it may be said in passing that in some districts the wheat went as high as 60 bushels to the acre, while a fair average throughout the country was about 25 bushels to the acre, an exceedingly good figure—in spite of this crop, there was not a great deal of profit for the farmer in sight. The cost of the seed grain, the implements, the labor of putting in the crop, and finally the harvesting had all to be taken into account. Added to this was the considerable item of threshing, the hauling of the grain to market, the excessive freight rates and, as mentioned above, the drop in the price of grain. Only by close figuring could the farmer arrive at the figure of $4 per day for the stookers. Also it should be borne in mind that most of these stookers were “green” and knew not the first thing about farming. Of that more anon.

As I have said we started the harvest at $4 per day for the stooker, but hardly a week had gone by when the wage rose to $5, and then shot up to $6, and even $7, and some of the big outfits towards the end of the season were paying $8 a day to the stooker.

It is a fact that the farmer could not make a profit and pay such prohibitive wages. The result was that many of them clubbed together and helped each other to harvest their own grain. Some of the farmers left their grain unstooked in the field, declaring it would be cheaper not to thresh then pay such wages. Motoring over the country we saw fields and fields of unstooked grain lying on the ground, and in every instance the farmer asserted that he was unable to get stookers save at the prohibitive wage mentioned above. Nevertheless during that period the streets of Calgary were thronged with idle men, and the government employment office was full of men waiting for jobs to be called at the wages demanded. Many a farmer went up and down the streets, personally soliciting the men, and offering the highest wage he could afford to pay without a distinct loss.

Threshing

Came the threshing. The previous year bundle throwers had been satisfied with $4 per day and board. This year they demanded and got $6, and some outfits paid $7 and $8. The man on the separator got from $5 to $20 a day, according to the outfit. The man on the engine, where he was not the owner of the outfit, drew his $19 to $25 a day. Cooks were paid $8 to $12 a day. Forced to pay these excessive wages the threshing outfits charged the farmer from 13 to 17 cents per bushel.

When the cost of putting in, harvesting, threshing and marketing that crop is taken into account, one wonders what there was left for the farmer’s work. Grain has an inclination to strike the toboggan just as harvesting ends, and with the shortage of cars always at this season, and the uncertain weather, which makes the hauling of the grain to the elevators anything but a comfortable job, the farmer deserves our sympathy.

Winter Jobs

While threshing was in progress, came emissaries from the War Veterans’ Association, from the C.P.R., from the government, and from other fraternal and charitably inclined associations, who made a farm to farm canvas on behalf of the English harvesters, soliciting homes and positions for “the men who crossed the sea to harvest your crop for you.”

That is what they said to the farmer. That was their preachment and part of their propaganda the facts that they—the government and the railroad—had brought these men to the country and, no doubt, had made promises of winter employment. At all events many of the men assured me that this was the case. They took the solution of the problem of caring for the men to the already overburdened farmer, and they pointed out to him that here was an opportunity to have good strong workers at a lower wage than that paid experienced hands.

Just here I might point out that an inexperienced hand on a farm or a ranch often costs in losses from incompetence and ignorance far more than his wages could pay for. As an instance I might mention one Englishman who was a perfect dub about tools and implements. I don’t believe he knew a screw driver from a wrench, and every implement upon the farm was “a plough” to him. Nevertheless he acquired a passion for hammers, and he would hammer and bang everything into the shape he thought it should be, with the result that an astounding number of implements were most perniciously bent and injured. Another Englishman who had averred that he was used to and understood horses, put to work at summer following, used the ingenious method of stopping his horses by pulling at their tails and calling “Whoo-a-a.” The horses took fright and were soon off in a bad run-away. Three horses, with badly skinned shins against a barbed wire fence, a twisted and partly broken disc and an Englishman limping ruefully home with a sprained ankle, which laid him up for a week or two, were the net result of this adventure.

However, this is all part of the “game.” We are not hard on the men who make these kind of mistakes through ignorance, and we know that often the greenest tenderfoot will sometimes turn out the best of workers, once he has learned his job.