“How old are you, O-Yasu-san?”

The speaker, a very large and languid-looking Englishman, was seated on a stool, hard by the little table at which O-Yasu-san knelt. He was regarding the girl with a degree of interest mixed with humor, and occasionally his eye wandered craftily in the direction of his hostess, and always hers met his in a curious look of meaning.

O-Yasu paused a moment before answering the query addressed her. Then she looked directly at Mr. Middleton, and he forgot his question in unexpected internal speculation on the color of her eyes. They were golden, fringed with silken lashes of black. He thought of yellow-petaled daisies. Then her small, staccato voice, with its queer little ring of sarcasm, reached him:

“Thas not perlite question you mek,” she said, “and my honorable aunt say in England nize gintle-man not call maiden by her Clistian name.”

He laughed, and gave her more attention now.

“Well, but we are in Japan,” said he, “and it is polite here to inquire a person’s age—-is it not? Don’t you Japanese consider that a compliment?”

“I am not Japanese,” said O-Yasu-san, and put four lumps of sugar viciously into the Englishman’s cup—-a thimble in size—-adding as she handed him the sickly-sweet beverage:

“In Japan thas perlite you dring all thas given unto you.”

He tasted, then regarded her in mock reproach.

“You are not Japanese, I quote,” said he, “and I refuse, therefore, to suffer.”

Whereupon he set his cup down, and O-Yasu quite unaccountably fell to tittering and giggling to herself in a curiously suppressed, yet wholly youthful, fashion. Mr. Middleton watched her, his hand curled up near the side of his upper lip, where once a military mustache had flourished. “I am curious to know if you are laughing at me,” said he.

“I god liddle joke all in my own haed,” said Yasu, smiling vividly. “Some day I tell you. You want hear?”

“I am perishing to,” he said.

“Very well,” said she. “To-mollow, perhaps, I telling you.”

“Oh, I am to see you, then, to-morrow?”

“Yaes—-you want see me?”

“I intended to ask you if I might.”

“Aevery day,” said Miss Yasu, lowering her voice confidentially, “I take liddle walk out to Shiba Park. You know that white lotus pool? Thas where I like go—-er-—mebbe, to-mollow.”

“Good!” exclaimed the Englishman, and, under the watchful eye of his hostess, he reached across and took O-Yasu’s little limp hand in his and shook it cordially. Then he smiled but it was at Mrs. Tom his smile was directed.

A little later, shaking hands with his hostess, in that affected uplifted mode then prevailing in society, she said, smiling teasingly-—there were a dozen friends at hand:

“Aha! my friend, another conquest for our little maid, eh?”

He responded more warmly than they had agreed upon: “Quite adorable—-altogether——” The rest was lost in the hubbub of chatter about them, but what he actually conveyed to Mrs. Tom’s ear was this:

“Easy as fishing. Little lady herself arranged it all. Didn’t have to suggest seeing her again. She even mentioned Shiba Park--the place of rendezvous agreed upon. Everything is falling in, apparently, with our plans. The gods wish us well, it seems.”

Mrs. Tom’s voice was raised, her face seemed grave, in spite of its seeming graciousness. Her friends heard her say:

“How sweet of Yasu-san. We shall be delighted, of course. I’m sure every one will envy me my little task of chaperon. Yasu is only a little girl—-a mere child, you know. To-morrow, then. Good-night!”

Now, O-Yasu-san said nothing to her aunt of her engagement with Mr. Middleton, but, the following day, she appeared at the pool in question, a perfect little flower in appearance, gorgeous in purple kimono, flowered obi, gay parasol and glossy hair, bright with gilded ornaments. She found her swain in the company of Mrs. Tom, who surveyed her very benignly.

“Ohayo gozaramazu,” said Yasu, bowing extravagantly to the Englishman, and then very coldly to her aunt:

“Goo-by. I got nize ingagement make a talk with this English mister. Please mek excusing yourself.”

“Dear,” said Mrs. Tom, in her most syrup-like tones, “young English girls must always be chaperoned, you know. I couldn’t think of letting you be alone with Mr. Middleton, my dear.”

O-Yasu snapped her parasol closed, and said crossly:

“I am not English-jin.”

She sat for some time thereafter on the curved stone wall of the pool, apparently oblivious of the two a short distance removed from her, and certainly themselves oblivious now of her presence. O-Yasu contemplated the sparkling-bodied goldfish and dropped pebbles, one by one, into the water. But, in the midst of some very ardent declaration, Mr. Middleton’s eyes encountered the sidelong contemptuous smile of O-Yasu-san. He colored to the ears and said in a rough whisper to Mrs. Tom, “Careful!”

She glanced about with the stealthy look of the guilty, and he crossed to O-Yasu at the pool. She leaned over the water, and he, watching her, saw that she was laughing in that elfin way of the previous evening.

“Oh, Miss Yasu, you were going to tell me, last night, some secret. Don’t you remember?”

“Anudder day I tell my liddle—-no, grade big joke on you.” “On me?”

“Yaes.” Her eyes big and innocent. “I telling on you.” “Tell me, too,” chimed in, sweetly, her aunt.

She shook her head vigorously now.

“I naever tell unto you,” she said.

“Why?”

“Be-cause you gotta big mouth. You speag all things loud-—mek big noises. I nod telling you.”

And having oracularly delivered this astonishing snub-—a truth, moreover—-to her speechless aunt, she deliberately turned upon that lady a small, disdainful back, decked with an obi butterfly bow of huge dimensions.

Mrs. Tom looked up at her friend. Then she turned a trifle pale. He was laughing.

The meetings at the pool occurred daily now—-even on rainy days when, arrayed in preposterous rubber coats, they sought the shelter of some flowering arbor. And every day O-Yasu laughed to herself, and said she had a “joke,” and sometimes she would make believe to tell her “joke.” Once it was a bunch of hair, which she withdrew from the bosom of her kimono. It belonged to her aunt. Yasu had playfully hidden it to show to the foreign mister. Another time she appeared with her aunt’s shoes upon her own diminutive feet, and, in the midst of her innocent mirth, showed the gentleman the size of the same. And again she appeared “writing on her eyebrows,” aunty’s pencil being useful for that purpose. And so on, until, bit by bit, she had playfully stripped the lady of all her clever feminine devices to stop the march of time upon her beauty. And always the Englishman-—laughed.

O-Yasu had become a vital factor in this curious triple courtship. It was said among the foreign colony that the Englishman was a suitor for the hand of O-Yasu-san.

Mrs. Tom’s plans had been more than successful, and she had reached a stage now where she found herself attempting to unravel the net in which she had unconsciously enmeshed herself. She had acquired an almost abnormal hatred for her niece; for, though the girl had made possible her daily meetings with her lover, yet Mrs. Tom had awakened to the electrical fact that O-Yasu-san was acutely aware of her manoeuvres. She tried to convey this discovery to her lover, but O-Yasu, always obtrusively close at hand, overheard the words and stood before them a picture of obtuse innocence.

“Make no mistake about Yasu,” had said Mrs. Tom bitterly, “she knows exactly why we come here.” The Englishman had whispered feeling words of the apparent innocence and sweetness of the “child.”

“Yaes, yaes, me knows—-me knows allee ‘bout it,” asserted Yasu sweepingly. “Mister Middleton—-he—-he-—lub me. Thas vaery nize. Thangs. Much’bliged. All lide. Me mek marry wiz you ride ’way. Put you nize head mos’ respectfully unto my august father’s most honorable feet. Say like this: ‘Guv me your most beautiful daughter.’ My fadder say: ‘She is nudding but a worm, but tek her. Help youself. When you like marry?’ Then I am ad liddle hole on fusuma. I rush in quick like thees,” and she illustrated with a rush toward the Englishman, seizing his hands impetuously in her own. “I say: ‘Ride away, ride away mek that marriage. Hoarry. I got liddle joke telling him.’ Then my fadder say: ‘What is thad joke?’ And I answer at once, like filial daughter, ‘I lub him—-and he also lubbing me. Thas my joke,’” and she brought out the word “love” with such fervid violence that the Englishman tingled; and a good part of that night he spent smoking under the stars, repeating to himself over and over again:

“And to think that was my poor little devil’s joke. What a——-I am.”

Mrs. Tom took to writing letters to him:

“My dear Jim:”

“Wake up. Beware of that little Japanese fraud. Believe me, she is absolutely alive to——”

And, just then, O-Yasu-san looked over her shoulder.

“Why,” said she, “you writing unto my lubber! ‘Jim’! Thas hes beautiful name of heem. What you writing?” For Mrs. Tom had crushed up the letter and now sat with it clenched in her delicate fist. She stood up suddenly, her eyes narrowed menacingly. From her queenly height she looked down at little dwarfed O-Yasu. For a moment they surveyed each other in silence. Then O-Yasu said, in that guileless, naive way which never deceived her aunt for a moment:

“Never mind, I see thad letter some udder day. All hosbands read those letters to their wives. Mr. Meedleton going show me thad letter some day.”

Mrs. Tom spoke succinctly:

“You and I understand each other perfectly, O-Yasu. I will tell you one thing, however. You will never marry Jim Middleton, and, in a few days, I will see that you are returned to your own people—-the people to whom you really belong.”

The following morning the Marquis Hakodate called solemnly upon Mrs. Thomas J. Bailey, and most of the morning was shut up in her room with her. Alas! the hotel walls were not paper shoji and O-Yasu was unable either to see or hear; and a prying maid in her confidence who had crawled along a perilous rain pipe to gain egress in some way to the room, was observed by a stupid, open-mouthed bell-boy, who, a lover of the aforesaid maid, gallantly ascended another drain pipe to rescue her. Whereupon, a wordy war ensuing, the argument came to a violent end, maid and boy crashing down to the court below and picking themselves up ruffled and bruised from head to foot.

Presently O-Yasu-san was called into the room. Her father’s face was yery grave; her aunt smiled upon her.

11 “O-Yasu, dear,” said she,

“your papa deems it expedient that your marriage to the Marquis Momoso should take place immediately. I congratulate you upon your good fortune.”“Thangs,” said little Yasu dryly, but she turned her eyes inquiringly upon her father. Still grave, he said briefly: “Have your insignificant belongings packed at once, my daughter, as I wish you to return with me to your home this evening.”

After a deep bow signifying obedience to her father, O-Yasu turned a beaming face upon her aunty.

“Thangs ag’in,” said she; “you mos’ kind aunty in all the whole worl’, b-but please permit me stay wiz you liddle bit longer,” she pleaded.

“My dear little girl,” said Mrs. Tom, smiling graciously, “I only wish you could stay with me longer, but, of course, it must be as your father says.”

Whereupon, O-Yasu turned to her father quickly. His eyes regarded her tenderly and lovingly, for, it had been many days since he had seen her. She said:

“Dear my father, it is the wish of my honorable aunty that I should stay with her much longer, and she begs that you permit it.”

This was said in Japanese, while Mrs. Tom drew her brows petulantly together, and clasped her finger in nervous exasperation. Bowing deeply, the Marquis Hakodate said in English, a language he spoke perfectly:

“I thank you, madame. It is very kind of you to wish the longer stay of my daughter, but——”

“Oh, please, pl-ease, father,” coaxed little O-Yasu, seizing his hands, and holding them tightly, and entreating his glance. He coughed uneasily, for he had been made aware of the danger from the designing Englishman pursuing his daughter. “Please, permit me to remain,” begged O-Yasu, tears in her voice now.

“Till to-morrow, then,” said he gruffly; “to-morrow morning—-at eight o’clock, you must leave.”

O-Yasu looked piteously at her aunt, who was looking above the child’s head into space. Then she said meekly, “Thangs. Vaery well. I will go home to-morrow—-at eight.”

The following morning, some time before sunrise, she shook into wakefulness her grumbling but finally excited and curious maid, and for some time thereafter the two fell back and forth into each other’s arms, thus smothering back the ebullient mirth which possessed them. In the gray of the morning the gaping-mouthed bell-boy spied them stealing forth, but he told no one. He was in the secret—-via the maid. Also his services were required.

When Mrs. Tom, at seven A. M., discovered that O-Yasu was gone, and with her her maid and all her petty belongings, a thrill of fear shot through her. Some women would have reasoned that O-Yasu had returned to her home. Not so Mrs. Tom, who at this time was palpitating with all the intuitions of a woman guiltily in love. Her mind could jump to startlingly true conclusions. That is why the address she gave to the runner who brought the jinrikisha to her was the same as that given earlier in the morning by O-Yasu to a public jinrikiman of Tokyo.

Mrs. Tom’s boy, however, flew swiftly to the southward, while O-Yasu’s man had gone east. And Mrs. Tom’s boy stumbled as they passed through one of those strange waste places of the city which seem almost like deserted country—-stumbled, fell, and broke the shaft of his vehicle. So there was Mrs. Tom, doomed to wait—-and wait-—and wait, until the gaping bell-boy should return from his quest for another carriage.

Meanwhile: Rap! rap! rap! on the woodwork of the English mister’s room. A murmured grumble inside. Rap! rap!

“What is it?”

“Veesitors, Excellency,” shrilled the English mister’s “boy,” a weazened, wise old fellow of sixty.

“Visitors,” exploded the voice within. “What the——”

“You, Tomagawa, what do you mean by waking me at this hour?”

“Veesitors!” patiently repeated Tomagawa, a note of reproach in his voice.

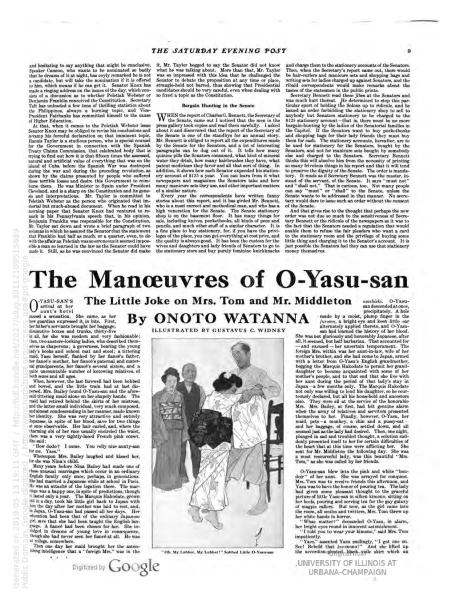

A noise heard inside—-the tramp of a heavy man, barefooted, across the floor. Then the door opened a crack. As it did so a little figure darted forward, thrust itself through the aforesaid crack, and, a moment later, Mr. Middleton found himself encircled in the convulsive arms of Miss O-Yasu Bailey Hakodate. Her maid had also entered the room, quite as a matter of course, and she now stood off at a respectful, admiring distance, examining the bare legs of the foreign mister from several oblique angles.

“Oh, my lubber, my lubber!” sobbed little O-Yasu-san, clinging frantically to his waist—-she had tried vainly to reach his neck. “Soach a trubble—-soach a trubble.”

The speechless Englishman with one desperate pull freed himself from the embracing arms, threw one agonized look about the apartment and, with a dash, plunged into his bed—-the only modest place of hiding for a decent gentleman. Curious the moral sense of Mr. Middleton, who thought nothing of making love to another man’s wife, yet panically hid his naked limbs from the innocent gaze of little O-Yasu-san. However, she followed him swiftly across the room to his place of refuge, and now, upon her knees, she wailed aloud her “trubbles.”

It seemed she had a cruel, ugly old aunt, who hated O-Yasu very much. She had sent for O-Yasu’s father and had told him many wicked lies about her dear lubber (and she put her face fondly and warmly against the hand which she clutched tightly with her own). She, the ugly, very old aunt—-she was very near forty, perhaps more—-asserted O-Yasu, had told the Marquis Hakodate that he, Mr. Middleton, was in pursuit of his daughter. Her honorable father—-a descendant of a thousand samurai, she asseverated, was greatly enraged, and was now looking all over Tokyo for the despoiler of his house. He had with him the two sharp swords of his ancestors, and he intended certainly to run them through the heart of her dear, dear lubber. Therefore, she, weak and helpless as she was--and here she let fall a sob, which induced the Englishman to put his free hand over the little one clinging to his other one—-had come thus early to save his life. She knew that his intentions were of the most honorable, for had not he always courted her in the presence of a chaperon—-the very aunt herself? But how could they make the Marquis Hakodate believe this also? Why—-simply by an immediate marriage. (Here the Englishman let fall her hand and regarded her with his eyes bulging out, and his mouth gaped open.)

It could be easily arranged, urged O-Yasu. Why, there was a clergyman—-a “Clistian” she called him—-just around the corner, and she had brought a jinrickisha right to his very door for the purpose. She stopped, sat back on her heels and regarded her “lubber” in a most engaging manner.

“Miss O-Yasu,” said he, when he had found his voice, “please go outside for a moment. I won’t be an instant getting into my things.”

“You going to do it?” she questioned joyfully, astounded at her own success.

“You mean, marry you?”

“Yaes.”

“If you will have me,” said he, quite simply.

She had arisen now, and stood looking at him a bit uncertainly. Then:

“Sa-ay, I got you sk-skeered mebbe?” “No.”

“Sa-ay,” she was retreating now toward the door, “I—I just meking liddle joke ad you. I gotter make nudder kind marriage. Me? I just want disgusting you at my honorable aunt, account her hosband, my honorable uncle. Aexcuse me—-I going now.” She had reached the door now.

“O-Yasu!”

She stood still, looking at him somewhat fearfully now.

“You will wait for me, won’t you?”

“My fadder nod goin’ kill you,” said she. “Thas lie. I jus’ want mek liddle marriage wiz you for liddle bit while, till my honorable aunt go away. Then I, gittin divorce, ride away. Git marry agin wiz my honorable Marquis Momoso.”

“Very well,” said he cautiously. “Then wait outside; there must be a marriage, however.”

“Ye-es,” she hesitated, and then cried out:

“No, no—-I got a changing of mind now. I not going mek you do that. Good-by!”

“Tomagawa!” shouted the Englishman at the top of his voice, and then, as the weazened face of his “boy” appeared at his door, he added peremptorily:

“Hold this young lady till I can join you.” “Sertinly, Excellency,” smiled Tomagawa, and seized little O-Yasu by the sleeve, holding her a prisoner.

By and by, fully dressed, Mr. Middleton opened the sliding doors of his chamber. For a while he stood in silence, his arms folded, looking at O-Yasu. Then quietly: “You may go, Tomagawa. I will take your place.” Released, O-Yasu remained still, her shamed eyes avoiding the Englishman’s, but, when he put his arm about her, she laid her face against his coat and began to cry.

After a time:

“You goin’ mek me marriage wiz you, mister?”

“Yes, Yasu-san.”

“Why?”

“Because—-I’m-—I’m quite mad about you,” said he. “But my honorable aunty?” “There was no ‘aunty’ for me, Yasu, after the second time I saw you.”

“Oh,” said she. “Then, if thas so—-then—-then my honorable uncle not going lose her ride away.”

“I suppose not. We won’t talk about it. Come. Are you willing?”

“Yaes,” she nodded.

“Why?”

“Same reason you got,” said she. And they went out together.

Mrs. Tom Bailey lay in her shaded room. She still shook and trembled from her late seizure. Ever since her return from the house of the Englishman she had gone from one fit of hysterics into another. One moment her mind was flooded with the imagined scenes of the past few months; she saw herself the central figure in a quiet, perfectly-refined little every-day divorce-—later an accidental meeting with her friend, and still later a marriage. And then, jumping in, like an elf, upon these mind

22 pictures, fluttered the gaudy, mocking little form of O-Yasu-san, and she clenched her delicate fists at the thought. About her wisps of rice-paper were scattered like snow, the pieces of O-Yasu-san’s letter which she had torn to pieces in a frenzy:

“Darling Aunty Tommy:”

“I got marriage with Mr. Middleton,” wrote the jade. “Listen, honorable aunt-in-law, I did not intend making this beautiful elopement with that loavely man. I just want making revenge on you, because I listening at the shoji on that day you making plan with him—-for just little bit while, so you can see him much. I say that I going unto that Englishman making a big raddle and noise. Mebbe, he gitting skeered, and run away from Japan. But he not want doing thus. Say he got mad with love for me, and so we make that marriage, sure enough. That’s very nice. Thanks you for making me aquinted with my honorable hosband. Good-by. Mebbe my honorable uncle thank me also. Yes?” and she signed her name in dashing letters-—Japanese-—at the end.

Marie held the ice-bag over her mistress’ temple. She spoke thoughtfully:

“Madame was always better at zese times when m’sieu’ was wiz her. Perhaps, madame——”

Mrs. Tom buried her face deeply in her pillow. From there her muffled voice came:

“Cable, Marie—-cable—-cable. Say—-we are-—going-—home.”