Kasaka Yuka was young, and she was gentle and pretty; moreover, her father had been a Samourai, but he had been long since dead. Yet Yuka’s mother, Kasaka Onoto, who was but a poor peasant woman with none of the Samourai blood in her, nevertheless was very proud of her daughter, whose father had been a Samourai. That is why Yuka had all the sweet, courteous and refined ways of the Samourai; for what was not inbred in her had come to her from her very knowledge of her blood. So, though Yuka grew up in the midst of the peasant people, she came to be looked upon as one quite different from them.

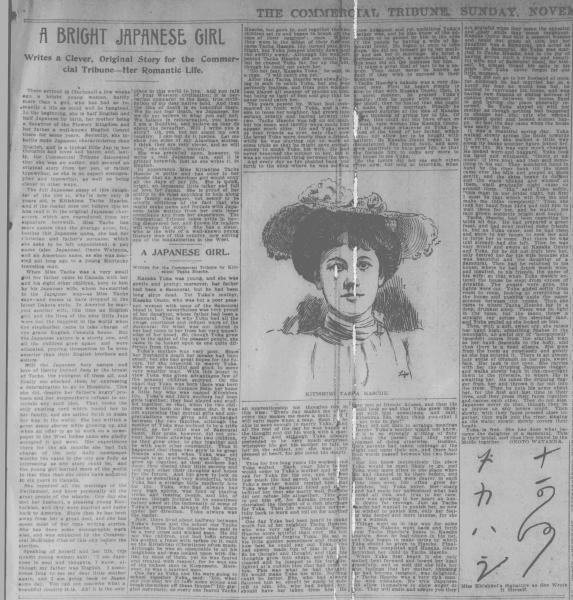

Yuka’s mother was very poor. Since her husband’s death her means had been small; but she had great hopes for the future, for she expected to marry Yuka, who was so beautiful and good, to some very wealthy man. With this intent in view Yuka was given advantages few of the peasant children enjoyed. On the exact day Yuka was born there was born only a very little distance from her home a little boy who was named Kitshima Ido. Yuka’s and Ido’s mothers had been girls together; they had played and studied together, so that, when the two children were born on the same day, it was not surprising that mutual gifts and congratulations were given and exchanged between the two families, although the mother of Yuka was inclined to be a trifle proud, as her child was of Samourai blood. Her pride, however, did not prevent her from allowing the two children, as they grew older, to play together and to be with each other constantly. Thus it happened that those two grew to be great friends also, and when Yuka was old enough to go to school, so was Ido. They grew up together, as their mothers had done; they shared their little secrets and told each other their thoughts and hopes for the future. And Ido grew to look on Yuka as something very wonderful, while Yuka had a strange little motherly love for Ido. Yuka, who had always very high spirits, was fond of playing tricks and teasing people, and Ido, of course, though inclined to be sometimes rather awed at the immensity of some of Yuka’s proposals, always did his share under her direction. Yuka always was the leader.

Now, there lived about halfway between Yuka’s house and the school one Tacha Hasche. This Tacha Hasche was said to be a very cross and wicked man. He did not like children, and had built around his garden a fence with spikes on it, such as the Kirishitan (Christians) often made. Although he was so unsociable to all his neighbors and was looked upon with dislike by most of them, yet he was feared and treated with respect, for he was the richest man in Kumomota. Moreover he was a married man.

One day as Yuka and Ido were going to school together Yuka said, “Ido, what say you that we do take some stones and break the spikes off these fences?” Ido giggled nervously, as every one feared Tacha Hasche, but gave in, and together the two children set to began to break off the tops of their neighbor’s fence. Whilst they were in the midst of their fun out came Tacha Hasche. Ido turned pale with fright, but Yuka jumped nimbly down and ran swiftly away. Although Ido was left behind Tacha Hasche did not touch him, but he chased Yuka far, far up the hill, though he could not catch her.

“Do not fear, Kasaka Yuka,” he said, in a rage. “I will catch you yet.”

After that Tacha Hasche was always lying in wait to catch Yuka, but she was perfectly fearless, and from pure wickedness played all manner of pranks on him, but being so light of foot and gay that he never could catch her.

The years passed by. What had commenced in frolic with Yuka, and a desire to tease her neighbour, had grown into serious enmity and hatred betwixt the two. Tacha Hasche was not an old man, but his mean and thrifty ways made him appear much older. Ido and Yuka were as dear friends as ever, only that now Ido loved Yuka more dearly than a friend, while he was starting out to work at some trade so that he might save enough money to make Yuka his wife. He had never broached the subject to her, but it was an understood thing between the two. And every day as Ido plodded back and forth to the shop where he was serving an apprenticeship his thoughts ran in this wise: “Every day makes me older; every day makes me more a man; and I will earn more when a man. Soon I’ll be able to save enough to marry Yuka,” and all the rest of the day he was happy and did his work with a merry heart. And although Yuka always pretended to be very much surprised whenever Ido got his mother to talk to her on the subject, yet she was very pleased at heart, for she loved Ido dearly, too.

Thus for five long years Ido worked and Yuka waited. Each year, Ido’s father would come to Yuka’s mother and would ask for Yuka for his son, and tell her how much Ido had saved, but each time Yuka’s mother would remind him that Yuka was of Samourai blood and it befitted her that she marry well. But she did not refuse Ido altogether. This was to put him off, for Kasaka Onoto still cherished the thought of a rich marriage for Yuka. Then Ido would turn sorrowfully back to work and toil on for another year.

One day Yuka had been heard to make much fun of her neighbour Tacha Hasche, who was very ugly. This made Tacha Hasche more spiteful than ever. He felt he never could forgive Yuka. He sat in his little garden sometimes and thought how best he could pay out Yuka, who had openly made fun of him in public. So he thought and thought, and then his thoughts grew into shape, and his face cleared and he jumped to his feet delighted at a sudden idea that had come to him. This was what he had thought: He would make Yuka his wife. Nothing could be better. She, who had always flaunted him so, should be made to submit to him. Ido, who had helped her, should have her taken from him. He knew how poor and yet ambitious Yuka’s mother was, and he also knew of the advantage to be gained by him in the eyes of the people by having a wife of Samourai blood. He began at once to take steps. He did not himself go to her mother and ask her in marriage. He hired a professional nakodo, a match-maker, and this man did all the business for him.

It takes a great deal of tact to be a nakodo. They must never be known as such if they wish to succeed in their business.

Tachaa Hasche’s nakodo was a very discreet man. First he began simply to stop to chat with Kasaka Onoto; then, in a quiet manner, he praised Yuka’s beauty; then he spoke with respect of her blood; then he hinted that she ought to make a great marriage. Finally he expressed surprise at the idea of Kasaka Onoto thinking of giving her to Ido. Of course, this could not but have effect on a weak, vain woman like Kasaka Onoto, but it had none whatever on Yuka because of the blood of her father, which would not allow her to be bought with flattery. So Kasaka began to be discontented. She found fault, and soon grew positively to hate poor Ido, so that she forbade him to come any more to the house to see Yuka.

So the lovers did not see each other often now, but only at intervals, when they met at friends’ houses, and then Ido would look so sad that Yuka grew impatient with him sometimes, and said “Kitishima Ido, what think you—that I be not true to you?”

They did not dare to arrange meetings whereby Yuka’s mother would not know, for it is so strongly a thing of duty to obey the parent that they never dreamed of doing otherwise. Besides, Ido’s parents had taken umbrage at the slight cast upon their son, and there had been words passed between the two families.

But Ido knew instinctively the places Yuka would be most likely to go, and Yuka went more often to one place when Ido had chanced to be there before, and thus they met and were dearer to each other than ever. Ido often grew despondent, but Yuka never. Her sharp mind had made her understand what had caused all this, and true to her race, there was growing in her heart an honest desire for revenge. Just as Tacha Hasche had wanted to punish her, so now she wished to punish him, only her feeling was deeper and more intense, for she was a woman.

Things went on in this way for some time. The Nakodo went back and forth from Tacha Hasche’s house to Kasaka Onoto’s. Soon he had Onoto in his net, and they began to make terms by which Yuka should be given to Hasche. Finally all was completed and Kasaka Onoto betrothed her child to Tacha Hasche.

When Yuka first heard it she only smiled, bent forward and bowed her head gracefully, and so well did she hide her true feelings, that her mother thinking she had become resigned, was delighted, for Tacha Hasche was a very rich man. She was mistaken. No true Japanese will allow themselves to show anger or pain. They will smile and assure you they are grateful when they mean the opposite, and their smile may mean vengeance. Kasaka Onoto was only a peasant woman and could not grasp at this, but her daughter was a Samourai, and acted as became a Samourai. So Yuka was married to Tacha Hasche, and in the joy of having gotten such a young and beautiful wife, and of Samourai blood, for himself, he almost forgot his spite in his pride. But Yuka never forgot for one little moment.

Yuka did not go to her husband at once, for although he had married her in a hurry for fear he would lose her, he wanted to rearrange his house, and was having new fusuma or sliding screens of opaque paper between the rooms fixed in and having the place generally renewed. So Yuka stayed on with her mother as though nothing had happened to change her life; only she seemed strangely quiet looked and almost happy. At last the day came when the house was ready for her.

It was a beautiful spring day. Yuka walked slowly across the fields towards the river. As she walked a little way along its banks another figure joined her. It was Ido. He was very much changed. He looked worn and haggard. Yuka took his hand and whispered, “Onoto oi asi musu” (I love you), and then said something in his ear. They wandered hand in hand by the river bank till the moon came over the hills and peeped at them gently, and the skies began to darken and the stars blinked and winked at them, until gradually night came on around them. “Ido,” said Yuko softly, “this must be our bridal night, but first I must do that which will free me and make me thine completely.” Then she took her hand from Ido’s and told him to wait there for her, and he waited, his face grown suddenly bright and happy.

Tacha Hasche had been expecting his bride all day. He had prepared a great feast, and had even invited some friends in, but no Yuka came, and he had risen and gone to her house to seek her and to force her to come. But there he was told already had she left. Then he was very wroth and swore at Kasaka Onoto and Yuka, for he did not truly love her, only desired her for his wife because she was beautiful and the daughter of a Samourai. Then he had returned to his house, where he had drunk much wine, and insulted, to his friends, the name of his wife; so that when Yuko meekly entered the house he slept from excess of drinking. The guests were gone, the lights were out. Yuka glided softly from room to room, looking at everything in the house and pushing aside the paper screens between the rooms. Then she came to where Tacha Hasche lay in a deep, drunken sleep. There was no light in the room, but the moon threw a straight ray across the sleeping man, and Yuka smiled as she looked on him.

Then, with a soft, sweet cry she raises her hand high; something flashes in the moonlight, an awful cry of “hotogoroshi” (murder) comes from the startled man as her hand descends to the body, and then there is a dead silence. She goes from the room as noiselessly and gently as she has entered it. There is an almost holy smile of triumph on her pale, sweet face. Her task is not over. She carries with her the dripping Japanese dagger, and walks slowly back in the moonlight down to the riverside, to where Ido is awaiting her. He takes the dripping dagger from her and throws it far out into the river. Then he puts his arms about her, for the first and last time in their lives, and they press their faces together and caress each other. They do not kiss. Japanese never do that, though they be as joyous as any lovers could. Then slowly, with their faces pressed close together, they walk into the river, singing as the water slowly, slowly covers their heads.

Yuka is free. She has done what became the daughter of a Samourai. This is their bridal, and thus they travel to the Meido together.