Chapter I

The Storm Dance

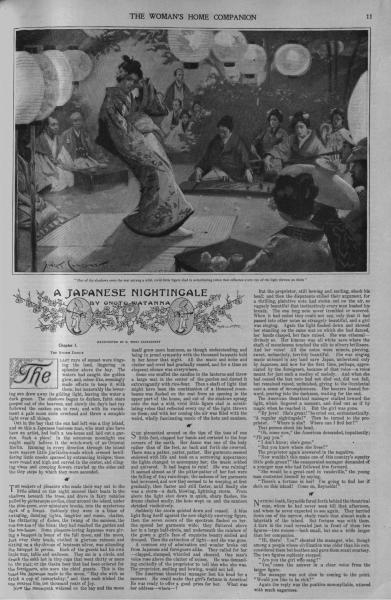

The last rays of sunset were tingeing the land, lingering in splendor above the bay. The waters had caught the golden glow, and, miser-like, seemingly made efforts to keep it with them; but inexorably the lowering sun drew away its gilding light, leaving the water a dark green. The shadows began to darken, faint stars peeped out of the heavens, and slowly the day’s last ray followed the sunken sun to rest; and with its vanishment a pale moon stole overhead and threw a seraphic light over all things.

Out in the bay that the sun had left was a tiny island, and on this a Japanese business man, who must also have been an artist, had built a tea-house and laid out a garden. Such a place! In the sorcerous moonlight one might easily believe it the witch-work of an Oriental Merlin. Running in every direction through the island were narrow little jinrikisha-roads which crossed bewildering little creeks spanned by entrancing bridges; these were round and high and curved in the center, and clinging vines and creeping flowers crawled up the sides and the tiny steps by which they were ascended.

The seekers of pleasure who made their way out to the little island on this night moored their boats in the shadows beneath the trees, and drove in fairy vehicles pulled by picturesque coolies, clear around the island, under the pine-trees, over miniature brooks, into the mysterious dark of a forest. Suddenly they were in a blaze of swinging, dazzling lights, laughter and music, chatter, the clattering of dishes, the twang of the samisen, the ron-ton-ton of the biwa: they had reached the garden and the tea-house. Some pleasure-loving Japanese were giving a banquet in honor of the full moon, and the moon, just over their heads, clothed in glorious raiment and sitting on a sky-throne of luminous silver, was attending the banquet in person. Each of the guests had his own little mat, table and waitress. They sat in a circle, and drank the saké hot in tiny cups that went thirty or more to the pint; or the Osaka beer that had been ordered for the foreigners, who were the chief guests. This is the toast the Japanese made to the moon, “May she with us drink a cup of immortality;” and then each wished the one nearest him ten thousand years of joy.

Now the moon-path widened on the bay and the moon itself grew more luminous, as though understanding and being in proud sympathy with the thousand banquets held in her honor that night. All the music and noise and clatter and revel had gradually ceased, and for a time an eloquent silence was everywhere.

Some one snuffed the candles in the lanterns and threw a large mat in the center of the garden and dusted it extravagantly with rice-flour. Then a shaft of light that might have been the combination of a thousand moonbeams was flashed on the mat from an opening in the upper part of the house, and out of the shadows sprang onto the mat a wild, vivid little figure clad in scintillating robes that reflected every ray of the light thrown on them; and with her coming the air was filled with the weird, wholly fascinating music of the koto and samisen.

She pirouetted around on the tips of the toes of one little foot, clapped her hands and curtsied to the four corners of the earth. Her dance was one of the body rather than of the feet, as back and forth she swerved. There was a patter, patter, patter. Her garments seemed endowed with life and took on a sorrowing appearance; the lights changed to accompany her; the music sobbed and quivered. It had begun to rain! She was raining! It seemed almost as if the pitter-patter of her feet were the falling of tiny rain-drops; the sadness of her garments had increased, and now they seemed to be weeping, at first gradually, then faster and still faster, until finally she was a storm––a dark, blowing, lightning storm. From above the light shot down in quick, sharp flashes, the drums clashed madly, the koto wept on and the samisen shrieked vindictively.

Suddenly the storm quieted down and ceased. A blue light flung itself against the now slightly swerving figure, then the seven colors of the spectrum flashed on her. She spread her garments wide; they fluttered above her in a large half-circle, and underneath the rainbow of the gown a girl’s face of exquisite beauty smiled and drooped. Then the extinction of light––and she was gone.

A common cry of admiration and wonder broke out from Japanese and foreigners alike. They called for her––clapped, stamped, whistled and cheered. One man’s voice rose above the clatter of noises. He was demanding excitedly of the proprietor to tell him who she was. The proprietor, smiling and bowing, would not tell.

The American theatrical manager lost his head for a moment. He could make that girl’s fortune in America! He was ready to offer a good price for her. What was her address––where––?

But the proprietor, still bowing and smiling, shook his head; and then the disputants stilled their argument, for a thrilling, plaintive note had stolen out on the air, so vaguely beautiful that instinctively every man hushed his breath. The one long note never trembled or wavered. When it had ended they could not say, only that it had passed into other notes as strangely beautiful, and a girl was singing. Again the light flashed down and showed her standing on the same mat on which she had danced, her hands clasped, her face raised. She was ethereal––divinely so. Her kimono was all white save where the shaft of moonbeams touched the silk to silvery brilliance. And her voice! All the notes were minors, piercing, sweet, melancholy, terribly beautiful. She was singing music unheard in any land save Japan, understood only by Japanese, and now for the first time, perhaps, appreciated by the foreigners, because of that voice--a voice meant for just such a medley of melody. And when she had ceased the last note had not died out, did not fall, but remained raised, unfinished, giving to the Occidental ears a sense of incompleteness. Her hearers leaned forward, peering into the darkness, waiting for the end.

The American theatrical manager stalked toward the light, which lingered a moment, and died out as if by magic when he reached it. But the girl was gone.

“By jove! She’s great!” he cried out, enthusiastically. “A regular nightingale!” Then he turned to the proprietor. “Where is she? Where can I find her?”

That person shook his head.

“Oh, come now,” the American demanded, impatiently; “I’ll pay you.”

“I don’t know, she’s gone.”

“But you know where she lives?”

The proprietor again answered in the negative.

“Now wouldn’t this make one of this country’s squatty little gods groan?” the exasperated manager demanded of a younger man who had followed him forward.

“She would be a great card in vaudeville,” the young man contented himself by saying.

“There’s a fortune in her! I’m going to find her if she’s on this island! Come on, Reynolds!”

Nothing loath, Reynolds fared forth behind the theatrical man, whom he had never seen till that afternoon, and whom he never expected to see again. They hurried down one of the narrow, shady roads that almost made a labyrinth of the island. But fortune was with them. A turn in the road revealed just in front of them two figures––two women––both small, but one a trifle larger than her companion.

“Hi, there! You!” shouted the manager, who, though among a people whose civilization was older than his own, considered them but heathen and gave them scant courtesy. The two figures suddenly stopped.

“Are you the girl who sang?”

“Yes,” came the answer in a clear voice from the larger figure.

The manager was not slow in coming to the point. “Would you like to be rich?”

Again the reply was the positive monosyllable, uttered with much eagerness.

12

“Good!” The manager’s face could not be seen, but his satisfaction was revealed in his voice. “Just come with me to America and your fortune’s made.”

She stood silent, her head down, so that the manager asked, impatiently, “Well?”

“I stay ad Japan,” she said.

“Stay at Japan!” The manager controlled himself. “Why, you can never get rich in this land! Now, look here; I’ll call and see you to-morrow. Where do you live?”

She shook her head. “I don’ lig thad you come. I stay ad Japan.”

This time the manager, seeing a possible fortune escaping and having in mind the courtesy due heathen, delivered himself of a large Christian oath. “If you stay here you’re a fool! You’ll never––”

The young man called Reynolds, who had watched the eager bargaining in silence, here broke in with some indignation. “Oh, let her go! She has a right to do as she pleases, you know. Don’t try to bully her into going to America if she’d rather stay here.”

“Well, I suppose I can’t use force to make her take a good thing,” said the manager, ungraciously. He drew out his card-case and handed the girl his card. “Perhaps you’ll change your mind after you think about this a bit. If you do, my name and Tokyo address are on that card; just come around and see me. I’m going down to Bombay to look out for some Indian jugglers. I’ll be gone about three months, and will be back to Tokyo before I leave for America.”

The girl took the card and listened in silence; when he finished she curtsied, slipped a hand into that of her companion and hurried on down the narrow road.

After the two Americans had made their way back to the tea-garden the older at once sought out the proprietor. “You surely know something about the girl; come, tell us,” he said.

The proprietor was profusely courteous, but hesitated to speak of the one who had danced and sung. Finally he unbent a trifle and told the theatrical man and the foreigners who had gathered about that he knew as little of the girl herself as any of them. She had come to him a stranger and had offered her services. Once he attempted to have her followed, but she had eluded him, and had made him promise never to follow her again. He judged she did not live in Tokyo. The remuneration for her services was slight, and he saw little of her. She came only at night, and he was under contract to see her safely across the bay to Tokyo, where she disappeared among the crowds. She came irregularly and only when it suited her whim, appearing when he least expected her and when he needed her most, on fêtes and occasions of this kind; but he had no means of finding her. It was only by chance she happened to come on this night. She was unreal, uncanny, unlike any Japanese girl he had met, and he had handled many.

“She is beautiful,” some one said, almost reverently, after these disjointed statements had come to an end.

“No.” The manager hesitated a moment, and then added, “Not from a Japanese standpoint.”

“Why?” came in another voice from the crowd.

“Her eyes are blue, her hair red.”

Chapter II

In Which the Woman Proposes and Man Disposes

Laurin Reynolds was beset by the nakodas (professional matchmakers). He was known to be one of the richest foreigners in the city, and the nakodas gave him no rest. Though he found them excessively interesting, with the little comedies and tragedies to relate of the matches they had made and unmade, he had remained impregnable to their insinuating arts. He naturally shrank from such a union as the nakodas proposed, and in this position he was strengthened by a promise he had made to a college chum before leaving America, his most intimate friend, a young English-Japanese student named Taro Burton; a promise that during his visit in Japan he would not append his name to the long list of foreigners who cheerfully take unto themselves Japanese wives and with the same cheerfulness desert them.

Taro Burton was almost a monomaniac on this subject, and denounced both the easy-going foreigners who took to themselves and deserted Japanese wives, and the native Japanese who made such a practice possible. He himself was a half-caste, being the product of a marriage between an Englishman and a Japanese woman. In this case, however, the husband had proved faithful to his wife and children up to his death; but then he had married a daughter of the nobility, a descendant of the proud Jokichi family, at one time lords of all KumammottaKumamoto. Despite the happiness of this marriage Taro was bitterly opposed to the union of the women of his country with men of other lands, particularly as he was Westernized enough to appreciate how lightly such marriages were held by foreigners. It was true that after the desertion the wife was divorced according to the law, but that, in Taro’s mind, only made the matter more detestable.

For five years, up to their graduation five months before this, the young American and the young Japanese had been as closely associated as it is possible for two young men to be, and a strong and deep affection existed between them. It had been originally decided that the friends would make this trip together--which in Taro Burton’s case was to be his return to the home he had left as a mere boy, and for Laurin Reynolds was to be the beginning of a year’s travel preliminary to entering the business of his father, who was a rich ship-builder. But for some reason, which he never clearly set forth to his friend, Taro had backed out at almost the last minute; yet he had urged Laurin to undertake the trip alone, and, under promise to follow shortly, had finally prevailed. So Laurin had made the long journey to Japan, and two weeks before had taken a very pretty house of his own a short distance from Tokyo. With a little man and maid to attend him and care for his house he was far better off than if he had been at an American hotel, where most of the foreigners put up, living just as they did at home and missing all the real life of the country.

It was unfortunate that Taro could not accompany Laurin Reynolds, for while the latter was not a weak character, he was easy-going, good-natured and easily manipulated through his feelings. The young Japanese would at least have kept the nakodas and their offerings of matrimonial happiness on the outer side of the American’s door. As it was, one of them in particular was so picturesque in appearance, quaint in speech and persistent in his calls that Laurin had encouraged his visits, and a certain amount of intimacy existed between them.

It was this nakoda––Ido was his name, as he had told Laurin––who one day brought an applicant for a husband to Laurin Reynolds’ house and besought the American at least to hold a “look-at” meeting with her. “She is so beautiful lig the sun goddess,” were the words with which the match-maker ended his inventory of her charms. Then he added, entreatingly, “Just have a little loog-ad meeting.”

“Well, for the fun of the thing, then,” said the young man, laughing, “I don’t mind having a ‘loog-ad’ meeting with a pretty girl, I’m sure. Show her into the zashishi (guest-room); but you’d better understand that I don’t intend to marry any one; at all events, not a girl of that class.”

“Nod for a liddle while whicheven?” persuaded the nakoda.

“Nod for a liddle while whicheven,” echoed Laurin; but the agent disappeared. When Laurin, curious to know what she was like who was seeking him for a husband, entered the zashishi he found the blinds high up and the sunshine pouring into the room. His eyes fell upon her at once, for the shoji at the back of the room was parted, and she stood in the opening, her head drooped bewitchingly. He could not see her face. She was small, but not quite so small as the average Japanese woman, and the two little hands clasped before her were the whitest, most irresistibly perfect hands he had ever seen. He had heard of the beauty of the hands of Japanese women, and he knew she was holding them so that they could be seen to advantage. Her little affected pose amused and pleased him.

After he had looked at her a moment she subsided to the mats and made her prostration. She was dressed very gaily, and a sweet subtle odor exhaled from her gar- ments. Her hair was arranged after the fashion of the geisha, with two huge poppies on either side; but as she kept bobbing and making her absurd yet delightful curtsies to him some pin slipped, and a tawny, rebellious mass of hair, which was never meant to be worn smoothly, fell all about her, tumbled into her eyes and over her ears and literally covered her. She shivered in shame at the mishap, and then knelt very still at his feet. Laurin was speechless. Never before in his life had he seen such hair. It was dark, though not densely so, for all over it, even where it had been darkened with oil, there was a rich red tinge; and it was luxuriously thick and long and wavy.

“Good heavens!” he said, after the little figure had remained absolutely motionless for a full minute, “she’ll hurt or cramp herself in that position. Please stand up.” The nakoda told him to lift her to her feet, and the young man did so, entangling his hands in her hair. When she stood up he saw her face, which was oval and rosy, her lips very red. She still drooped her eyes, so her face was incomplete.

“What’s your name?” he asked her, gently. “What do you want with me?”

Now she raised her head and he saw her eyes. They startled him. They were large, though narrow, and intensely, vividly blue. Before, with her hair neatly smoothed and dressed, he had noticed nothing extraor- dinary about her; now, with that rich, red-black hair enshrouding her, and the large, blue eyes looking at him mistily, she was an eery little creature that made him marvel. A Japanese girl with such hair and eyes! And yet there was no other country she could belong to. She was strangely Japanese, and yet strangely unlike any Japanese he had seen. He wondered vaguely to himself whether there was a certain class of that people whose eyes were blue and whose hair was tinged so.

“You are Japanese?” he finally asked, to make sure. She nodded.

“I thought so; and yet–-”

She smiled, and as she did so the eyes closed a trifle. She was all Japanese in a moment and prettier than ever.

“You see, your eyes and hair–-” he began again. She nodded and dimpled and he knew she understood.

“What is it you want?” he asked, desiring rather to hear her speak than to learn her object, for this he knew.

She was solemn now. She blushed and her eyes went down. To explain to him why she had come to him in this wise was a painful task. He could guess that. But she forced the words past her lips.

“To be your wife, my lord,” she said in English; and the queer quality of her voice thrilled him strangely.

This was the answer he knew was coming: nevertheless it stirred him in a way he had not expected. To have this wonderfully pretty girl before him beseeching him to marry her--he who had as yet never dreamed of marriage for himself--was disturbing to his balance of mind. Nay, more; it was revolting. He shrank back involuntarily, wondering why she had come to him for this, and this wonder he put into words.

“But why do you want to marry me?” he asked.

The expression of her face was enigmatical now. She had ceased altogether to blush and smile and had become quite white. Suddenly she commenced to laugh--thrilling, elfish laughter, that rang out through the room, startling the echoes of the house.

“Why?” he repeated, fascinated.

She shrugged her shoulders. “I mus’ make money,” she said.

Of course this was her reason; he knew that before she spoke; but hearing her say so gave him pain; she was such a dainty little body.

“Oh, you need not sell yourself for that,” he said, earnestly. “Why, I’ll give you some, all you want. You’re awfully young, you know, aren’t you? Just a little girl. I can’t marry you. It wouldn’t be fair to you.”

Again she shrugged her shoulders and spoke in Japanese to the nakoda. “She says some one else will,” he interpreted.

“All right,” said the young man, almost bitterly.

She pretended to go slowly toward the door, and then came back toward Laurin. “I seen you before,” she announced, ingenuously.

“Where?” He was curiously interested. He fancied her face familiar.

“Ad tea-house.”

“What tea-house?”

“On liddle island. You ‘member? I danze like this” she performed a few steps.

“What? You that girl?” He knew her in an instant now. “How could you remember me?”

“You followed me after danze with another American gent. And before thad some one point ad you. Ole wooman thad always accompanying me.”

“How did she know me?”

“She din know you to speag ad, bud–” she hung her head a moment– “she telling me I bedder git married with you.”

“Why?”

“Ah––tha’s account she knowing I luffing with you––”

“You loving with me!” He laughed outright. Her ingenuousness was entrancing.

“Yes,” she said; and he, with masculine conceit, half believed her.

“But wouldn’t you rather stay at the tea-house than get married?” he asked.

“Not nuff moneys that business,” she returned.

“Do you do everything for money?”

“How I goin’ live?” This question answering a question brought her back to the purpose of her visit. She held her little hands out to him. “Ah, augustness, pray marry with me!” she begged.

He took her hands quickly into his own. They were soft and so small. He could inclose them in one of his. He knew they were daintily perfumed, like everything else about her. He did not let them go.

“You ought not to marry, you know,” he said to her, almost boyishly. “How old are you?”

She ignored this question.

“I will be true good wives to you forever,” she said: and then corrected herself swiftly, as though frightened by her own words, “No, no; I make mistake not forever; just liddle while, as you desire, augustness!”

“But I don’t desire,” he laughed, nervously. “I don’t want to get married! I won’t be over a few months, at most, in Japan.”

“Oh, for a liddle while marry with me,” she breathed, entreatingly, “pl-ease!”

He put her hands quickly from him. She held them out and put them back again into his. Her eyes clouded and he thought she was going to cry. He was seized with a desire to keep her from weeping if he could––this little creature who seemed made for anything rather than for tears. He spoke from this impulse without giving so much as a second’s thought to the seriousness of his words.

“Don’t cry. I’ll marry you, of course, if you want me to.”

He felt the hands in his own tremble. “Thangs, augustness,” she said, in a voice that was barely above a whisper, but it was a voice which had in it no note of joy.

There was pleasure, however, in the eyes of the nakoda.

He had done a good piece of business––a most excellent piece of business––for the American gentleman was reputed to be able to buy hundreds and hundreds of rice fields if he cared to do so. The nakoda came forward with a benignant smile to arrange the terms.

It was the grinning face of this matrimonial middleman that brought Laurin to his senses. He had said he would marry this little creature whose limp hands he was holding. He dropped them as though they were the hands of one dead, and drew back.

“I won’t do it!” he almost shouted. “Never!” Then he thought what must be the feeling of the girl whose offer of marriage he was refusing, and softened. “I wasn’t thinking when I said I would! I wouldn’t be doing right, and it wouldn’t be fair to you!” He paused, and then added, lamely, “I think I’d like you ever so much, though, if I only knew you.”

“But––” spoke up the nakoda, anxiously, who found his dream of a large fee fading into thin air.

Laurin turned upon him quickly and gave him a sharp look, whereat he retired hurriedly.

A look of relief had come over the girl’s face when Laurin had cried out that he would not marry her, and at this he wondered much. This relief in her face was succeeded almost instantly by disappointment. But she spoke no further word. She gave him a single hurried glance from beneath fluttering eyelashes, curtsied until her head was almost on a level with his knees, and left him.