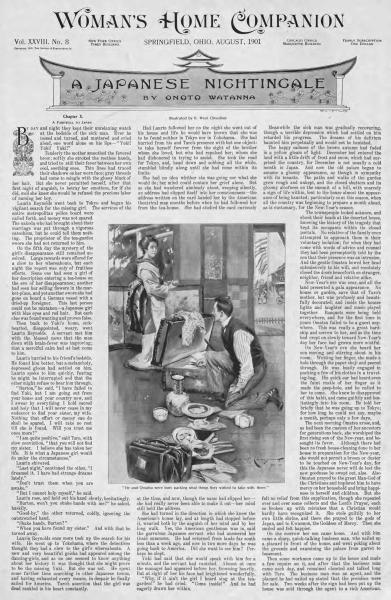

A Japanese Nightingale

Chapter X.

Farewell to Japan

By day and night they kept their unrelaxing watch at the bedside of the sick man. Ever he tossed and turned, and muttered and cried aloud, one word alone on his lips—-“Yuki! Yuki! Yuki!”

Tenderly the mother smoothed the fevered brow; softly she stroked the restless hands, and tried to still their fever between her own cool, soothing ones. Thin lines had traced their shadows other worn face; gray threads had come to mingle with the glossy black of her hair. But she never permitted herself, after that first night of anguish, to betray her emotions, for if she did, well she knew she would be refused the precious labor of nursing her boy.

Laurin Reynolds went back to Tokyo and began his vigilant search for the missing girl. The services of the entire metropolitan police board were called forth, and money was not spared. The nakoda who had brought about their marriage was put through a vigorous catechism, but he could tell them nothing. The proprietor of the tea-garden swore she had not returned to him.

On the fifth day the mystery of the girl’s disappearance still remained unsolved. Large rewards were offered for a clew to her whereabouts, but each night the report was only of fruitless efforts. Some one had seen a girl of her description entering a tea-house on the eve of her disappearance; another had seen her selling flowers in the market-place, and yet another swore she had gone on board a German vessel with a dried-up foreigner. This last person could not be mistaken—-a Japanese girl with blue eyes and red hair. But each clue was found wanting and proven false.

Then back to Yuki’s home, sick-hearted, disappointed, weary, went Laurin Reynolds. A servant met him with the blessed news that the man down with brain-fever was improving; that a merciful calm had at last come to him.

Laurin hurried to his friend’s bedside. He found him better, but a melancholy, depressed gloom had settled on him. Laurin spoke to him quickly, fearing he might be interrupted and that the other might refuse to hear him through.

“Burton,”he said, “I have failed to find Yuki, but I am going out from your house and your country now, and I swear by everything I hold sacred and holy that I will never cease in my endeavor to find your sister, my wife. Nothing that effort or money can do shall be spared. I will take no rest till she is found. Will you trust me once more?”

“I am quite positive,” said Taro, with slow conviction, “that you will not find my sister. I believe she has taken her life. It is what a Japanese girl would do under the circumstances.”

Laurin shivered.

“Last night,” continued the other, “I dreamed it. I have had strange dreams lately.”

“Don’t trust them when you are awake.”

“But I cannot help myself,” he said, Laurin rose, and held out his hand slowly, hesitatingly.

“Burton, won’t you shake hands with me?” he asked, huskily. “Good-by,” the other returned, coldly, ignoring the outstretched hand.

“Shake hands, Burton?”

“When you have found my sister.” And with that he turned away.

Laurin Reynolds once more took up the search for his wife. He went up to Yokohama, where the detectives thought they had a clew to the girl’s whereabouts. A new and very beautiful geisha had appeared among the dancing-girls, and as no one seemed to know anything about her history it was thought that she might prove to be the missing Yuki. But she was not. He spent some further time searching in other Japanese towns, and having exhausted every means, in despair he finally sailed for America. Tare’s assertion that the girl was dead rankled in his heart constantly.

Had Laurin followed her on the night she went out of his house and life he would have known that she was to be found neither in Tokyo nor in Yokohama. She had hurried from his and Taro’s presence with but one object: to take herself forever from the sight of the brother whom she loved, but who had repulsed her; whom she had dishonored in trying to assist. She took the road for Tokyo, and, head down and sobbing all the while, stumbled blindly along until she had come within its limits.

She had no idea whither she was going nor what she would do; her mind could contain her grief alone. But as she had wandered aimlessly about, weeping silently, an address had slipped itself into her consciousness—-the address written on the card handed her by the American theatrical man months before when he had followed her from the tea-house. She had studied the card curiously at the time, and now, though the name had slipped her—-she had really never been able to make it out—-her mind still held the address.

She had turned in the direction in which she knew the American’s house lay, and at length had stopped before it, wearied both by the anguish of her mind and by her long walk. Yes, the American gentleman was in, said the garrulous Japanese servant who had answered her timid summons. He had returned from lands far south less than a week ago, and now in two more days he was going back to America. Did she want to see him? Perhaps he slept.

Yuki had said that she would speak with him for a minute, and the servant had vanished. Almost at once the manager had appeared before her, frowning heavily. But at sight of her his face had brightened wonderfully.

“Why, if it ain’t the girl I heard sing at the tea-garden!” he had cried. “Come inside!” And he had eagerly drawn her within.

Meanwhile the sick man was gradually recovering, though a terrible depression which had settled on him retarded his progress. The dreams of his delirium haunted hint perpetually and would not be banished.

The happy sadness of the brown autumn had faded in a yellow gleam of light. December had entered the land with a little drift of frost and snow, which had surprised the country, for December is not usually a cold month in Japan. And now the old palace began to assume a gloomy appearance, as though in sympathy with its tenants. The paths and walks of the garden grew rough and unkept, and the closed shutters and its gloomy aloofness on the summit of a hill, with scarcely a sign of life within, lent to the house almost the appearance of being haunted; particularly so at this season, when all the country was beginning to prepare a month ahead, as is customary, for the New-Year’s season.

The townspeople looked askance, and shook their heads at the deserted house, knowing the history of the tragedy that kept its occupants within its closed portals. No relative of the family even attempted to approach them in their voluntary isolation; for when they had come with words of advice and counsel they had been peremptorily told by the son that their presence was an intrusion. And the gentle Omatsu bowed her head submissively to his will, and resolutely closed the doors henceforth on stranger, neighbor, friend and relative alike.

New-Year’s eve was near, and all the land presented a gala appearance. No house or garden, save that of Taro’s mother, but was profusely and beautifully decorated; and inside the houses lights and laughter and music played together. Banquets were being held everywhere, and for the first time in years Omatsu failed to be a guest anywhere. This was really a great hardship and sorrow to her, and as the time had crept on slowly toward New-Year’s day her face had grown more wistful.

On New-Year’s eve she heard her son moving and stirring about in his room. Wetting her finger, she made a hole through the paper shoji and peered through. He was busily engaged in packing a few of his clothes in a traveling-bag. His quick ear had heard even the faint rustle of her linger as it made the peep-hole, and he called to her to come. She knew he disapproved of this habit, and came guiltily and hesitatingly into his room. He told her briefly that he was going up to Tokyo; for how long he could not say, maybe a month, perhaps only a few days.

The next morning Omatsu arose, and, as had been the custom of her ancestors for generations back, she worshiped the first rising sun of the New-year, and besought its favor. Although there had been no fresh house-cleaning done in her house in preparation for the New-year, she would not permit a broom or duster to be touched on New-Year’s day, for this the Japanese never will do lest the new goodness be swept out, also. Also Omatsu prayed to the great Man-God of the Christians and implored him to have mercy on her household and bring happiness to herself and children. But she felt no relief from this supplication, though she repeated over and over some collects and the Lord’s Prayer, each so broken up with mistakes that a Christian would hardly have recognized it. She stole guiltily to her own little shrine, and there she prayed to the gods of Japan, and to Kwannon, the Goddess of Mercy. Then she smiled and felt happier.

On the morrow her son came home. And with him came a sharp, quick-talking business man, who nailed up a placard in front of the house, and went poking about the grounds and examining the palace from garret to basement.

Then some workmen came up to the house and made a few repairs on it, and after that the business man came each day, and remained closeted and talked long with Taro. The business man was an agent, and the placard he had nailed up stated that the premises were for sale. Two weeks after the sign had been put up the house was sold through the agent to a rich American.

2

After paying the agent’s fee Taro found himself with something over ten thousand dollars. He went down to Tokyo and deposited one thousand dollars of this to the account of Laurin Reynolds. This was about the amount his sister had received. He did not know that it was Laurin who was the purchaser of the house.

For a few days afterward he and Omatsu were busy packing what things they wished to take with them. Taro believed absolutely in the death of his sister, and could not bear to remain in Japan, so he and his mother were going to America. He had determined to devote his life to some good work there. Was his mother willing to accompany him? “To the end of the world and beyond that,” she had replied, and had been rewarded by the tenderness of his kiss, which drowned the sigh that welled up from within.

“We may not ever again be happy,” said Taro, sadly, “but we cannot continue here in uselessness; not I, at least.”

Chapter XI.

Five Years After–-A Japanese Nightingale

In the changeable heat of a New York summer the city is abominable. The Reynolds had not as yet left their city home for the country, though June had entered in a dirty cloud and sweltering heat. Laurin was at home, but he had come back to them a changed man. It was five years since he had left Japan. Of his wanderings, his vain searching, shattered hopes and harrowing disappointments there is no need to speak; Suffice it that he had spent his days in one absorbing purpose—-to find his wife. It was only the pleading solicitation of a mother that finally brought him home for a season.

Sunshine had been the dominant element in Laurin Reynold’s character, and, in a lesser degree, impulsiveness and generosity. No one had ever given him credit for deep thought, intensity of feeling and greatness of purpose. But sometimes tribulation will bring out such qualities which have laid hidden beneath an apparently superficial exterior.

A deep, abiding love for his summer bride had sprung into eternal life in the man’s heart. She was never absent from his mind. There were moments when for a time he would forget his immeasurable loss, and would drift backward into memory, and in fancy re-live again with her that dream-summer. She had become the soul of him! He was the despair of his old-time friends and the target of all their curiosity. Of what had occurred across the sea his lips were sealed. At first he tried to seclude himself from them; and when at his insistent request they left him to himself he grew intensely restless and ineffably miserable.

Here at home, in the midst of his kith and kin, a strange homesickness grew upon him for another land. Foreigners in Japan often jocosely speak of an attachment they acquire for the country as the “Lotus fever,” and some declare no traveler in the country is ever free from a taint of it. But this man had more than merely been touched by the fever; the land was immeasurably dearer to him than his own, for there he had left his heart and soul.

The Reynolds family were really lingering in the city beyond their wonted time in hopes of frustrating Laurin’s plan to return to Japan in August. Their friends had all left the city, and the world in which they moved had slipped away from them. Jean Reynolds, a happy-go-lucky fellow of twenty, full of good-nature and fun, was the moving spirit of the family. Shrewder in such matters than his sisters or mother, he had gained some inkling of the cause of his brother’s restlessness. He set out, as he expressed it, “to jolly him up,” and in his effort to accomplish this regaled him with the gossip of the clubs, dragged him out protesting, and kept the poor fellow on the move continually.

In this search after amusement Jean one evening proposed that Laurin go with him to a social settlement on the East Side, where, according to that young gentleman, a new prophet had appeared; a tireless zealot who was attacking the methods of certain charitable organisations; a man who preached a charity like Christ’s own, and who, because of his methods and the following he was gaining among the poor, had attracted the attention of the press and of certain society people, who were ever on the lookout for a new thing.

“And what is more,” said Jean, anxious, perhaps, to add a bit of spice to his argument, “they say that a certain actress has fallen under his spell, and that several times in the week she attends his meetings, heavily veiled, and watches him from an obscure corner of the room. Nobody knows who she is; the man himself doesn’t know, but still she follows him. It smacks of the unusual.”

Laurin smiled. The vagaries of a reformer or the repentance of an actress did not interest him; and finding him unresponsive to this his fertile-minded brother suggested their going to a certain roof-garden, which, he said, had an attraction billed that everybody was talking about and that could not fail to interest Laurin. “It is ‘A Japanese Nightingale’,” said Jean.

“Oh!” said Laurin, and he went a trifle pale. Like a whisper out of the past the memory of the Japanese nightingale sang about his ears.

And suddenly there came a note divine!

A throb of ecstasy, a sound entrancing,

Such as the gods invoke,

Trembled, and rose, and broke;

Was it the moon that spoke

Through the leaves glancing?

He remembered reading the lines somewhere.

1 They were very beautiful and true, he thought. Could theatrical scouts bring that voice of peerless beauty to this land, and would the bird, indeed, sing to such an audience as filled Gotham’s roof-gardens? Something choked him; he rose to his feet, went to the window and looked out at the lights of the great metropolis. Memories crowded in upon him, He thought of the bird that had made its home in the tall bamboo out in the midnight garden of his own little house. It had sung to them in foul and fair weather. Then there came a night when they waited in vain for the sweet, haunting voice. Their little guest had flown. Its loss had been as keenly felt as though it had been human. This was shortly after that terrible hedge of constraint had grown up between him and his little wife, and he had been infinitely cruel to her.

One night at dusk, after an exceedingly sad and chilly meal indoors, he had gone out alone and was trying to soothe his senses with a fragrant cigar. Instinctively he was waiting for his wife; he missed her if she was absent from his side but a moment. Suddenly out of the gloaming came the one long, shrill note of sheer ecstasy and bliss, that quivered and quavered a moment and then floated away into the maddest peal of melody, ending in a soh of agony that was excruciating in its intense humanness. The nightingale had, returned! tle sprang to his feet, and standing by the veranda-rail stared out into the darkness. And then? A woman came out of the shadows of their garden, and under the light of the moon she looked up into his eyes, and murmured, in a voice thrilled by an inward sob, so timid and weak, so beseeching and prayerful:

“I lige please you, my lord”!

“The nightingale!” he whispered, with hoarse emotion; “it has returned!”

“Nay, my lord; tha’s jus’ me! I jus’ a liddle echo!” She had learned the voice of the nightingale!

It all came back to him now, suffocating and oppressing him. He was here in this great, gorgeous drawing-room, and between him and his wife stretched thousands and thousands of miles of land and water. He was here, and she—-where was she?

“What is it, old man?” It was his brother’s voice. “You are shaking like a leaf, and as white as death.”

With a supreme effort Laurin regained his scattered senses and stood straight and somber against the window.

“I was thinking,” he said, gently. “Let us go to-night and hear the nightingale sing.”

The roof-garden was a popular resort, and as usual it was crowded, for its attractions were said to be of the best. The waiters were kept busy filling the glasses, and the men smoked and the women chattered even while the performance was on.

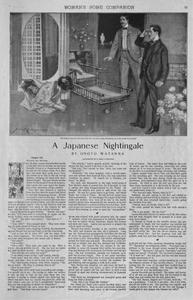

A couple of athletes were wriggling around on the stage, one holding the other on his head. They brought forth vociferous applause from the men. After their departure a couple of comedians occupied the stage for a time, and then the black and white card changed, and the letters spelt out simply, “A Japanese Nightingale.”

An expectant hush settled over the crowd; then some one started clapping, which set the house going, so that it was quite a little reception which greeted the bird of the Orient.

The curtain rising disclosed a poor imitation of Japanese scenery; but the lights were well used, and had the effect of softening the stage. Then the lights went out all over the house, including the stage, and through the hush that usually follows the darkening of a theater stole out upon the air that same wild note that had thrilled the heart of Laurin Reynolds in Japan. He sprang to his feet, breathing heavily. After that first note the darkness vanished from the stage, leaving it a pale yellow in tint, and then the audience saw that the nightingale was a woman-—a young girl—-and she stood singing there a song without words or accompaniment, only the clear, piercing, syrup notes of a human nightingale.

There was a commotion at one of the tables. A man had started across the darkened theater, and then had fallen with a crash.

Outside the theater Jean Reynolds tried to force his brother into a cab. He thought he had lost his senses. Dazed and stupid from his fall in the dark Laurin had at first made no resistance; but when Jean tried to get him to enter the cab he fought madly for his freedom.

His brother took his arm and tried to steady him. “All right, old fellow. Look out, or you’ll break the window! Be calm a minute!”

“I must go back!” his brother was telling him.

“What for? Do you know that girl who sang?” asked his brother, quickly.

“She is my wife!”

The silence was almost tragic. Jean had released his hold on his brother, and his young face looked white and ghastly beneath the lights of the street.

“It can’t be true,” he whispered, hoarsely. “She is the woman who follows that chap who is making all the noise down in the social settlement. One of the fellows knows a reporter who watched her and found it out, but his paper wouldn’t print it.”

“It is a lie!”

A little later Laurin Reynolds stood before a private entrance to the stage, over which hung the sign, “No admission.” He was accosted by the doorkeeper, and requested to leave. Laurin took out his card and handed it to the man feverishly. “I must see her,” he said, unsteadily. “It is a matter of life and death with me.”

“Who?”

For a moment his mind floated, “The Japanese singer,” he said finally.

The man glanced at the card. He recognized the name; the family was well known. “She’s just going,” he volunteered, civilly. “But—-”

“I must see her.”

“Step this way,” he said, reluctantly.

“You have my card,” said Laurin, following; “if ever I can—-”

“That’s all right.” The man knocked at a door.

“Come,” sounded a voice from within. His guide opened the door, turned aside for Laurin to pass through, and then closed it behind him.

32

He stood still a moment, undecided and nervous beyond his control. It was a dressing-room in which he found himself, and it had only one other occupant besides himself. She stood before a mirror fastening a veil about her face. There was no maid to attend her. Her figure was slight, and she was enveloped from head to foot in a long opera-cape, the hood drawn half way across her head. She doubtless thought that the one who entered was some other actress, for she did not turn her head.

Laurin stared at her dimly. He could not see her face; but the one he sought had been wont to deck herself in all the colors of the Orient, while this girl was surely an American.

Having tied the veil she turned about, stooped a moment to pick up a small bag, and then looked up. Standing silently in the doorway, blocking her exit, she saw a man, a stranger. She was not a girl to scream or faint, but she went gray with fear, and stood perfectly still there in the middle of the room. Then gradually her eyes traveled upward to the man’s face, and there they remained entranced.

For a long while they faced each other thus, both with hearts that seemed not to beat. Then the man made a movement, toward her—-a passionate, wild movement—-and she had dropped the bag from her hand and had gone to meet him. The next moment he was crushing her to him. When he released her but an instant it was to hold her again, and yet again, as though he feared to find her gone and his arms empty once more, as they had been for so long. He could only breathe her name, “Yuki! Yuki! Yuki! My wife! My wife!”

Neither tried to explain. There was time enough for that. They were absorbed alone in the feet that they were together at last!

And then came some one—-it matters not who-—into the room, and he released her grudgingly.

“You—-you will take me to my home?” Her voice was all broken and quivering, but as exquisitely sweet in its soft intonations as ever. It went to the man’s heart and warmed him up like wine.

“No—-to mine—-to our home,” he breathed in her ear.

They went out into the night together.

Through the quiet streets they wandered, like simple children. The hand he had drawn through his arm in starting he was now holding closely between both his own. Each saw nothing but the other, and neither knew whither their steps led.

At length Laurin asked, softly, his mouth almost against her ear, “But what became of you that night, Yuki?”

And then she told him of going to the home of the American theatrical manager in Tokyo, and of how kindly he had dealt with her in the years since; how she had secured an American teacher, who always traveled with her and how she had studied unceasingly. And what had he done?

“Since that night I have thought of but one thing—-you. I have done but one thing—-search for you. And now you are glad that we have met again?”

She drew even nearer him in answer. Then she hurriedly, yet with hesitation, her eyes clinging to the pavement, said, “When I think of those first days I am ashamed.” She was speaking almost as correctly as could be, though with an inflection and accent that were delicious; she must have studied, he thought. “I knew no better, I loved Taro—-and there seemed no other way. I didn’t care for you at first. But—-”

A hand placed softly upon her mouth stopped the sentence, “Don’t, Yuki. Your mother told me all. You are far nobler than the rest of us. It is not fit that you should make apology to me.”

With her free hand she drew Laurin’s from her mouth and pressed it closely against her cheek, and went on speaking barely above a whisper. “But at the last I cared for you, my—-my husband—-and I have loved you ever since.” For a moment or more Laurin stood on the apex of happiness; he could not see, he could not think. Then like a flash his brother’s words obtruded themselves into his consciousness, and a sudden fear drew him from his high place. He paused to question her. Who was this man? He must know. He waited for her answer.

She stepped in front of him. A fugitive wind came up from the sea. Her hood had fallen back, and she had lost her veil. Her hair blew across her face. She was wearing it loosely, in Western fashion, and it became her well. A strand of it swept across his hand on her shoulder, and he stopped and kissed it reverently.

“I love you with all my soul,” he said. “Do not laugh at me now; I cannot stand it.”

She said, “I will never laugh at you more, my lord.”

“Tell me who—-”

“He is my brother”

He started violently.

“Taro that man! Ah, I might have known. Does he know—-does he let you work like—-like—-”

“Alas, no!” she said, wistfully. “I have been afraid to make myself known to him because he was so angry with me.”

“Nay, he loves you. He understands everything now. Have you never gone to him?”

She shook her head, hiding her face a moment against his hand. He thought her sobbing in the silence, and then that sweet laughter of hers sifted out on the night air, thrilling him with an ecstasy of tenderness.

His arms were about her. Her head on his breast. He thought the birds had come up from the country and were singing in the dark streets. The air was fresh and balmy. A cab rolled up slowly, and he hailed it. He lifted her bodily in his arms. She was very light. She had always been so. At the cab door he still held her, as he gave the driver directions.

Inside she asked him whither they were going.

“To Taro,” he said, “together.”

THE END