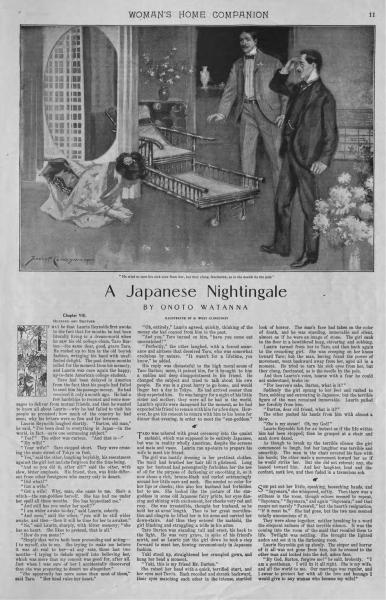

Chapter VIII.

Husband and Brother

It may be that Laurin Reynolds first awoke to the fact that for months he had been literally living in a dream-world when he saw his old college chum, Taro Burton—-the same dear, good, grave Taro. He rushed up to him in the old boyish fashion, wringing his hand with unaffected delight. The past dream-months rolled for the moment from his memory, and Laurin was once again the happy, up-to-date American college student.

Taro had been delayed in America from the fact that his people had failed to send him his passage-money. He had received it only a month ago. He had a few hardships to recount and some messages to deliver from mutual friends, and then he wanted to know all about Laurin—-why he had failed to visit his people as promised; how much of the country he had seen; why his letters were so few and far between. Laurin Reynolds laughed shortly. “Burton, old man,” he said, “I’ve been dead to everything in Japan—-in the world, in fact—-save one entrancing subject.”

“Yes?” The other was curious. “And that is-—”

“My wife!”

“Your wife!” Taro stopped short. They were crossing the main street of Tokyo on foot.

“Yes,” said the other, laughing boyishly, his resentment against the girl lost and she forgiven for the time being.

“And so you did it after all!” said the other, with slow, bitter emphasis. His friend. then, was little different from other foreigners who marry only to desert.

“Did what?”

“Got a wife.”

“Got a wife! Why, man, she came to me. She’s a witch—-the sun-goddess herself. She has had me under her spell all these months. She has hypnotized me.”

“And still has you under her spell?”

“I am wider awake to-day.” said Laurin, soberly.

“And soon,” said the other, “you will be still wider awake, and then—-then it will be time for her to awaken.”

“No,” said Laurin, sharply, with bitter memory; “she has no heart. She likes to pretend, that is all.”

“How do you mean?”

“Simply that we’ve both been pretending and acting—-I to myself, she to me. She trying to make me believe it was all real to her—-at any rate, these last two months—-I trying to delude myself into believing her which was more than my conceit was good for, after all. Just when I was sure of her I accidentally discovered that she was preparing to desert me altogether.”

“She apparently has more sense than most of them,” said Taro. “Her head rules her heart.”

“Oh, entirely,” Laurin agreed, quickly, thinking of the money she had coaxed from him in the past.

“And you,” Taro turned on him, “have you come out unscratched?”

“Perfectly,” the other laughed, with a forced assurance and airiness that deceived Taro, who was somewhat credulous by nature. “It wasn’t for a lifetime, you know,” he added.

His reply was distasteful to the high moral sense of Taro Burton; more, it pained him, for it brought to him a sudden and deep disappointment in his friend, He changed the subject and tried to talk about his own people. He was in a great hurry to go home, and would linger but a day in Tokyo. He had arrived sooner than they expected him. He was hungry for a sight of his little sister and mother; they were all he had in the world. Laurin’s spirits were dampened for the moment, as he had expected his friend to remain with him for a few days. However, he got his consent to return with him to his home for dinner that evening, in order to meet the “sun-goddess.”

Taro was ushered with great ceremony into the quaint zashishi, which was supposed to be entirely Japanese, but was in reality wholly American, despite the screens and mats and vases. Laurin ran up-stairs to prepare his wife to meet his friend.

The girl was hastily dressing in her prettiest clothes. The maid had brushed her hair till it glistened. Long ago her husband had peremptorily forbidden her the use of oil for the purpose of darkening or smoothing it, so it now shone a rich, bronze-black and curled entrancingly around her little ears and neck. She needed no color for her lips or cheeks; this also her husband had forbidden her to use. She looked like the picture of the sun-goddess in some old Japanese fairy prints, her eyes dancing and shining with excitement, her cheeks very red and rosy. She was irresistible, thought her husband, as he held her at arms’ length. Then to her great mortification and chagrin he lifted her in his arms and carried her down-stairs. And thus they entered the zashishi, the girl blushing and struggling a trifle in his arms.

Taro Burton was standing tall and erect, his back to the light. He was very grave, in spite of his friend’s mirth, and as Laurin put the girl down he took a step forward to meet her, bowing ceremoniously in Japanese fashion.

Yuki stood up, straightened her crumpled gown, and hung her head a moment.

“Yuki, this is my friend Mr. Burton.”

She raised her head with a quick, terrified start, and her eyes met Taro’s. Each recoiled and shrank backward, their eyes matching each other in the intense, startled look of horror. The man’s face had taken on the color of death, and he was standing. immovable and silent, almost as if he were an image of stone. The girl sank to the floor in a bewildered heap, shivering and sobbing. Laurin turned from her to Taro, and then back again to the crouching girl. She was creeping on her knees toward Taro; but the man, having found the power of movement, went backward away from her, aged all in a moment. He tried to turn his sick eyes from her, but they clung, fascinated, as is the needle by the pole.

And then Laurin’s voice, hoarse with a fear he could not understand, broke in:

“For heaven’s sake, Burton, what is it?”

Suddenly the girl sprang to her feet and rushed to Taro, sobbing and entreating in Japanese; but the terrible figure of the man remained immovable. Laurin pulled her forcibly from him.

“Burton, dear old friend, what is it?”

The other pushed his hands from him with almost a blow.

“She is my sister! Oh, my God!”

Laurin Reynolds felt for an instant as if the life within him had been stopped; then he grasped at a chair and sank down dazed.

As though to break up the terrible silence the girl commenced to laugh, but her laughter was terrible and unearthly. The man in the chair covered his face with his hands; the other made a movement toward her as if he would strike her. But she did not retreat; nay, she leaned toward him. And her laughter, loud and discordant, sank low, and then faded in a tremulous sob.

She put out her little, speaking, beseeching hands, and “Sayonara,” she whispered, softly. Then there was a stillness in the room, though echoes seemed to repeat, “Sayonara,” “Sayonara,” and again “Sayonara;” and that means not merely “Farewell,” but the heart’s resignation, “If it must be.” She had gone, but the two men seemed totally unconscious of it.

They were alone together, neither breaking by a word the eloquent sadness of that terrible silence. It was the coming into the room of the maid that recalled them to life. Twilight was settling. She brought the lighted andon and set it in the darkening room.

Laurin Reynolds got up slowly. The stupor and horror of it all was not gone from him, but he crossed to the other man and looked into the dull, ashen face.

“My God, Burton, forgive me!” he said, brokenly. “I am a gentleman. I will fix it all right. She is my wife, and all the world to me. Our marriage was regular, and I swear to protect her with all the love and homage I would give to any woman who became my wife!”

12

“Yes, you must do that,” said the other, with weak half-comprehension. “But where is she?”

“Where is she?” repeated his friend, dazed. The possible meaning of her withdrawal suddenly forced itself upon both of them. A dread of her possible loss possessed and stupefied Laurin, and Burton was half delirious.

“Let us look for her,” Laurin implored.

They called to her, and all over the house and through the grounds they searched for her, their lanterns scanning the dark shadows under the trees in the little garden; but only the autumn winds sighing in the pine-trees echoed her singing minor notes, and mocked and numbed their senses.

“She must have gone home,” said her husband.

“Let us go there at once,” said the brother.

“It will be all right, Burton, dear old friend. Trust me; you know me well enough for that.”

Taro paused and turned on him burning eyes, in which friendliness had been replaced by a look that spoke of stern and awful judgment.

“Otherwise,” he began, but paused, then went on, in a cold, hard voice, “I was going to say—-I will kill you!”

Chapter IX.

In Which Two Men Learn of a Sister’s Sacrifice

Even after they had boarded the train Laurin Reynolds’ usually sunny face was blanched to the ashiness of fear and despair. He was so nervous that he could not keep still, but kept jumping up and walking the length of the car, only to return and look, with eyes that attested the heartache within, at the other man, silent and grim. Taro seemed the more composed of the two; but well the younger man knew that beneath that subdued exterior slumbered a fire that needed but a breath to be turned into avenging fury.

Finally they reached their destination—-the little town which Laurin Reynolds had once before visited under different circumstances. There was no star or moon overhead to lighten their pathway; a dull, drizzly, sleety rain was falling. In silence they left the car, and in silence they plodded through the mud of the road and the damp grass of the field beyond. The little garden gate creaked on its hinges as they went through. They saw the dim outlines of the old palace before them, with its wide balconies and sloping roofs. Half way up the garden was the family pond, freshened by a hidden spring, and the little winding brook which wound hither and thither showed how it emptied into the bay beyond. There was even a tiny boat moored on a toy-like island in the center of the pond.

For the first time the Japanese paused and peered through the darkness at the scene before him. What were the memories that crowded back on him, suffocating him? Here it was that he and Yuki had grown up together. The little boat was the same, the island as small and neat, and the house seemed as ever; nothing had changed. Yes; where was Yuki? A deep groan involuntarily slipped from his lips.

There was a difference of seven years in their ages, but a stronger bond of sympathy and comradeship had existed between these two than is usual between brother and sister. Their mixed nationality had to a large extent isolated them from other children, for the Japanese children had laughed at their hair and eyes, and called them “Kirishitans” (Christians). Until he was seven years of age Taro had manfully, though bitterly, fought his battles with the Japanese children alone. He had been a queer, brooding little lad, of passionate and violent temper, and apparently scorning any overtures of friendship from any one outside his own household.

When the little sister had come, the boy had suddenly gone wild with joy, and had proceeded to bestow upon her the same worshipful love his mother gave exclusively to him, for Yuki had been born when their English father lay at the gates of death, her tiny soul fluttering into life just as that of her father’s drifted outward into eternity. To Omatsu, the mother, who was passionately absorbed in her grief, her arrival had been a source of irritation. But Taro had carried her to the family temple, and had himself named her “Snowflake” (Yuki), for she had come at a time when all the land was covered with whiteness. Moreover, she resembled a snowflake, so soft and white and pure.

How was it possible for him, after all these years, to come as he had come once more to this place, of which she had been always a part, and with which she had always been lovingly associated in his mind, and not be filled with emotions that tore at his heart? She had been his inspiration and all the world to him. He remembered how they would drift around in their tiny boat, and she, little autocrat, would perch before him, her eyes dancing and shining, while he told her the story of the fisher-boy, Urashima, and his bride, the daughter of the dragon king. And when he had finished, for the hundredth time, perhaps, she would say, “See, Taro-sama, I am the princess and you the fisher-boy. We are sailing, sailing, sailing, on the sea where summer never dies.” And he, to please her fancy, drifted on with her, around and around the little pond, till the sun began to sink in the west and the little haha (mother) would call them indoors.

Taro groaned again as he strode forward. When he knocked a man came shuffling from the rear of the house, and in reply to their inquiry for Madame Omatsu informed them gruffly that she had retired.

It did not matter; he must awaken her. Taro, who had found voice, told him this with such insistence that the servant fled ignominously to obey him. They waited for some time out in the melancholy night. There was no sound from within the house. Taro hammered on the door once more. Then a faint light appeared from a window close by the door, and the man’s head showed again, he begged their honorable patience, saying be would open in a fraction of a second. He was very humble and servile now, and as he admitted them, backed before them, bowing and bobbing at every step, for his mistress’ entire household had been taught to treat foreigners with the greatest deference and respect.

“Go to your mistress,” said Taro, briefly, “and tell her that her son desires to see her at once.”

There was a fluttering at the other side of the shoji. Taro saw an eye withdraw from a hole. There was a few moments of silence, and then the shoji parted and a woman entered the zashishi. Her mother-love must have prompted her to rush into the arms of her son, for she had not seen him in five years; but whatever her emotions, she skillfully concealed them, for the reason that her son was accompanied by a stranger, an honorable foreign friend, and it behooved her to affect the finest manners. Consequently, she prostrated herself gracefully, bowing and bowing, until her son strode rapidly over to her and lifted her to her feet.

She was quite pretty and very gentle and graceful. Her face, oval in contour, was smooth and unwrinkled as a girl’s, for Japanese women age slowly. It was hard to believe she was the mother of the tall man now holding her at arm’s length and looking down at her with such deep, questioning eyes.

“Where is my sister, Yuki?” he demanded, hoarsely.

“Yuki?” Madame Omatsu smiled, with saintly confidence.

She had retired. Would they pray wait till the morning? Ah! how was her honorable son, her august offspring? She began fondling her boy now, stroking his face, standing on tiptoe to kiss it, ecstatically smoothing and caressing his hands, feeling his strange clothes and laughing joyously at their likeness to those of her dear husband’s. But the dark cloud on Taro’s face was deepening, and he would not return or submit to his mother’s caresses until his fears regarding his sister were stilled.

“Send for her,” he said, briefly; and she knew he would not be gainsaid.

Send for her! Ah! Madame Omatsu begged her noble son’s pardon ten million times, but she had made a great mistake. His sister had, of course, retired, but it was not within their augustly miserable and honorably unworthy domicile. She had gone out on a visit to some friends.

Taro undid the clinging hands and pushed her from him, his brooding eyes glaring.

“Where?”

Where? Why, it was only a short distance—-perhaps two rice-fields’ length from their house.

“The house? The people’s names?” Madame Omatsu whitened; her eyes narrowed, her lips quivered. She tried once more frantically to prevaricate.

The people’s name? She could not quite recall, but the next day—-the next day, surely—-

“Ah-h!” said her son, with delirious brutality, “you are deceiving me—-lying to me! I demand to know where she is! I am her rightful guardian! I must see her at once!”

Madame Omatsu protested with faint vehemence, but she did not weep. She even essayed a little laugh that reminded Laurin verily of Yuki. In the ill-lighted room she looked strangely like her daughter, save that she was much smaller and quite thin and frail, whereas the daughter had been rosy and healthy.

Taro was speaking to her in Japanese, in a sharp, cruel voice, and she was answering gently, meekly, humbly. She seemed to be seeking to put him off and to propitiate him. Laurin felt sorry for her. Suddenly Taro threw her hands from him with a gesture of sheer despair and exhausted patience.

“I can learn nothing from her; nothing!” he said, in English. Then he turned on her again. “Listen,” he said. “You are my mother, and as such I honor you; but you must not deceive me. I know all; know that my sister was married to an American; know how she was married, if you call it a marriage. They do not consider it so, as you must know. What do you know of this, my mother? It surely could not have happened without your knowledge.”

The mother broke down at last. She saw that all was indeed lost if he knew that much. She sank in a heap at his feet, and again the other man was reminded of her daughter. Taro raised her, not ungently, curbing his emotions.

“Pray, speak to me the truth,” he implored. “It was for you,” she said, faintly, in Japanese. “I desired it—-I, your mother; and afterward she, also—-she, your sister. It was a small sacrifice, my son!”

“Sacrifice! What do you mean?” he cried.

“Alas! we had not the money to keep you at the American school. and later, when you desired to return, it was still harder.”

“Oh, my God!”

She went on, speaking brokenly in Japanese. After he had gone to America they had had ill luck and their little fortune had been practically swept away; but of this they had kept him in ignorance, fearing that he would not remain in the university if he knew how poor they were. They had secured money in what manner they could and sent it to him. It was hard, but they loved him. Then Yuki, unknown to her mother, had gone up to Tokyo each day and learned the arts of the geisha; later she had invented dances of her own, and soon she was enabled to command a good price at one of the chief tea-gardens in Tokyo.

This for a season had brought them a fair income, and for a time they were able to send him even more than the usual allowance. Then came his request for his passage-money. Alas, they were weak and silly women! They had forgotten to save against this event in their desire to keep him in comfort. Nakodas had approached Yuki, and tempting offers were made to her. She had resisted all of them, and only when it became imperative to raise the passage-money would she even listen to the persuasion of her mother and of the nakoda. They had pointed to her the great advantages, and finally, as the brother’s letters grew more insistent, she had broken down and given in. After that time she had assisted them in their efforts to secure her a suitable husband. They had been exceptionally successful, for she had married a foreigner who would likely leave her soon, which was fortunate in Omatsu’s mind; one whose excellent virtues and wealth were above question. This was all there was to tell. She had endeavored to act for the best in all things, and if she had done wrong she prayed and besought her honorable son’s pardon.

“Do you understand?” he turned on the other man. “It was for me my little sister sold herself! To keep me in comfort and ease! Snowflake—-for me! And they kept me in ignorance! I did not even dream they were in straitened circumstances!”

Laurin heard him, understood, and bowed his head in impotent sorrow.

“Does your mother know where she is?”

Taro had forgotten that they were seeking her. His mother’s story had held all his attention. The horror aroused by that recital of devotion, the thought of the months of her sweet life she had sacrificed for him, pressed on his poor, numbed senses. But Laurin’s inquiry recalled him. A thousand dark surmises regarding her overwhelmed him.

“Yes, yes, where is she?” he asked, huskily.

She had been with her husband some days now, but Madame Omatsu was expecting her home very soon, and this time she would never again return to her foreign husband.

Taro’s eyes were inflamed. “And she has not returned? She should be here now!”

All of a sudden he turned fiercely on his friend.

“You!” he cried, his accusing arm stretched toward him.

Then his arm fell limply at his side. The full agony caused by his sister’s disappearance and her great sacrifice swept upon him, and he tottered. Before Laurin could lay hands upon him he swayed forward, and as he fell struck his forehead upon the corner of a heavy chair that had been his father’s. When Laurin raised the head of the unconscious man he found blood flowing from a wide cut over the left eye.

There were hurrying feet throughout the house, terrified whispers and sobs, and above all a mother’s voice raised in terrible anguish.