A Japanese Nightingale (Part 3)

Chapter V.

The Adventuress

The man in the hammock was not asleep, for in spite of the lazy, lounging attitude, and the hat which hid the gray eyes beneath, he was very much awake and keenly interested in a certain small individual who was sitting on a mat a short distance removed from him. He had invited her several times to reduce that distance, but up to present she had paid no heed to his suggestion. She was amusing herself by blowing and squeezing between her lower lip and teeth the berry of the winter-cherry, from which she had deftly extracted the pulp at the stem. She continued this strange occupation in obstinate indifference to the persuasive voice from the hammock.

“I say, Yuki, there’s room for two in this hammock. Had it made on purpose.”

She continued her cherry-blowing without so much as making a reply, though one of her blue eyes looked at him sideways and then solemnly blinked.

“What’s the matter, Yuki? Got the dumps again, eh?”

No reply.

“Look here, Mrs. Reynolds,” said he, decidedly, “I’ll come over and elope forcibly with you if you don’t obey.”

She dimpled scornfully.

“Ah, that’s right! Smile, Yuki. You’re so pretty, so bewitching, so irresistible, when you look like that.”

Yuki nodded her head coolly. “How you lig’ me smiling forever?” she suggested.

“That wouldn’t do,” he answered, grinning at her from beneath his tilted hat.

“That’d be tiresome.”

“Tha’s why I don’ smiling today.”

“Why?”

“All yistiddy I giggling.”

He shouted with laughter at the word.

“Move your mat here, Yuki,” indicating a spot close to his hammock; “I want to talk to you.”

“My ears are––”

“Excessively small,” finished her husband.

“Please come!”

“Thangs,” with an air of great dignity. “I am quite comfor’ble here. I don’ lig’ sit so near you, excellency.”

“Why, pray?”

“Why––let me see! Hm! I understan’. Tha’s because I jus your liddle slave.”

“You’re my wife, you little fraud!”

“Wife? Oh, I dunno.” She pretended to deliberate.

“Then you’ve tricked me into a false marriage, madam!” declared her husband, with great wrath.

“Tha’s fault nakoda.”

“What is?”

“Thad you god me for wife, and,” slowly, “servant.”

“Fault! Come here, servant, then! Servants must obey.”

“Nod so bad master,” she laughed back, daringly.

“Besides, servant must sit long way off from master.”

“And wife?”

“Oh, jus’ liddle bit nearer.” There was a mischievous twinkle in her eyes as she edged perhaps half an inch closer to him. “Wife jus’ liddle bit different from servant.”

“Look here, Yuki, you’re not living up to your end of the contract. You swore to honor and obey––”

“Ah––hahahahaha––aaa––!”

“Yes you did, madam.”

“I din nod. Tha’s jus’ ole Kirishtan marriage.”

He sat up, amazed. “What do you know of the Christian marriage service?”

“Liddle bid.”

“Come over here, Yuki.”

“You lig’ me sing ad you?”

“Come over here.”

“How you lig’ me danze––liddle bit summer danze?”

“Come over here! What’s a summer dance, anyhow?”

She ran lightly indoors, and was back so soon that she seemed scarcely to have left him. She had slipped on a red and yellow flimsy kimono.

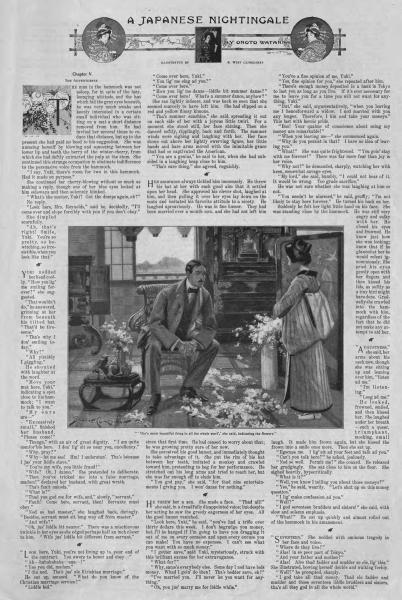

“Tha’s summer sunshine,” she said, spreading it out on each side of her with a joyous little twirl. For a moment she stood still, her face shining. Then she danced softly, ripplingly, back and forth. The summer winds were sighing and laughing with her. Her face shone out above her lightly swerving figure, her little hands and bare arms moved with the inimitable grace that had so captivated the American.

“You are a genius,” he said to her, when she had subsided in a laughing heap close to him.

“Tha’s sure thing,” she agreed, roguishly.

Her assurance always tickled him immensely. He threw his hat at her with such good aim that it settled upon her head. She approved his clever shot, laughed at him, and then pulling it over her eyes lay down on the mats and imitated his favorite attitude to a nicety. He laughed uproariously. He was in fine humor. They had been married over a month now, and she had not left him since that first time. He had ceased to worry about that; he was growing pretty sure of her now.

She perceived his good humor, and immediately thought to take advantage of it. She put the rim of his hat between her teeth, imitated a monkey and crawled toward him, pretending to beg for her performance. He stretched out his long arms and tried to reach her, but she was far enough off to elude him.

“You god pay,” she said, “for thad nize entertainments I giving you. I won’ danze for nothing.”

He threw her a sen. She made a face. “Thad all!” she said, in a dreadfully disappointed voice; but despite her acting he saw the greedy eagerness of her eyes. All the good humor vanished.

“Look here, Yuki,” he said, “you’ve had a trifle over thirty dollars this week. I don’t begrudge you money, but I’ll be hanged if I’m going to have you dragging it out of me on every occasion and upon every excuse you can make! You have no expenses. I can’t see what you want with so much money.”

“I gotter save,” said Yuki, mysteriously, struck with this brilliant excuse for her extravagance.

“What for?”

“Why, same’s everybody else. Some day I nod have lods money. Whad I goin’ do then? Tha’s bedder save, eh?”

“I’ve married you. I’ll never let you want for anything.”

“Oh, you jus’ marry me for liddle while.”

“You’ve a fine opinion of me, Yuki.”

“Yes, fine opinion for you,” she repeated after him.

“There’s enough money deposited in a bank in Tokyo to last you as long as you live. If it’s ever necessary for me to leave you for a time you will not want for anything, Yuki.”

“But,” she said, argumentatively, “when you leaving me I henceforward a widow. I nod married with you any longer. Therefore, I kinnod take your moneys.” This last with heroic pride.

“Boo! Your qualms of conscience about using my money are remarkable!”

“When you leaving me––” she commenced again.

“Why do you persist in that? I have no idea of leaving you.”

“What!” She was quite frightened. “You goin’ stay with me forever!” There was far more fear than joy in her voice.

“Why not?” he demanded, sharply, watching her with keen, somewhat savage eyes.

“My lord,” she said, humbly, “I could not hear of it. It would be wrong. Too grade sacrifice.”

He was not sure whether she was laughing at him or not.

“You needn’t be alarmed,” he said, gruffly; “I’m not likely to stay here forever.” He turned his back on her.

Suddenly he felt her light little hand on his face. She was standing close by the hammock. He was still very angry and sulky with her. He closed his eyes and frowned. He knew just how she was looking; knew that if he glanced at her he would relent ignominiously. She pried his eyes gently open with her fingers and then kissed his lids, as softly as a tiny bird might have done. Gradually she crawled into the hammock with him, regardless of the fact that he did not make any attempt to aid her.

“Augustness,” she said, her arms about his neck now, though she was sitting up and leaning over him, “Listen ad me.”

“I’m listening.”

“Loog ad me.”

He looked, frowned, smiled, and then kissed her. She laughed under her breath––such a queer, triumphant, mocking, small laugh. It made him frown again, but she kissed the frown into a smile once more. Then she sat up.

“Egscuse me. I lig’ sit ad your feet and talk ad you.”

“Can’t you talk here?” he asked, jealously.

“Nod so well. Permit me?” she coaxed. He released her grudgingly. She sat close to him on the floor. She sighed heavily, hypocritically.

“What is it?”

“Well, you know I telling you about those moneys?”

“Yes,” he said, wearily. “Let’s shut up on this money question.”

“I lig’ make confession ad you.”

“Well?”

“I god seventeen brudders and sisters!” she said, with slow and solemn emphasis.

“What!” He sat up quickly and almost rolled out of the hammock in his amazement.

“Seventeen.” She nodded with ominous tragedy in her face and voice.

“Where do they live?”

“Alas! in so poor part of Tokyo.”

“And your father and mother?”

“Alas! Also thad fadder and mudder so ole, lig’ this.” She illustrated, bowing herself double and walking feebly.

“Well?” he prompted, sharply.

“I god take all thad money. Thad ole fadder and mudder and those seventeen liddle brudders and sisters, tha’s all they god in all the whole world.”

“But don’t any of them work? Aren’t any of them married? What’s the matter with them all?”

“Alas! no; all of them too young to worg, excellency.”

“Too young!”

She nodded. “I oldest of all.”

“You?”

“Yes, me. How ole I am? I am twenty-eight; no, thirty years ole,” she declared, solemnly.

He nearly collapsed. He knew she was a mere child; knew, moreover, that she was lying to him. She had done so before.

“Even if you are thirty I don’t see how you can have seventeen brothers and sisters younger than yourself.”

She lost herself a moment. Then she said, triumphantly, “My fadder have two wives!”

He surveyed her in studious silence a moment. Her attitude of trouble and despair did not deceive him in the slightest. Nevertheless he wanted to laugh outright at her. She was such a ridiculous fraud.

“Do you know what they’d call you in my country?” he said, gravely.

She shook her head.

“An adventuress.”

“Ah, how nize!” She sighed with envious blissfulness. “I wish I live ad your country––be adventuresses.”

“How much do you want, Yuki?”

She pretended to calculate on her fingers. “Twenty-five dollars,” she announced.

He gave it to her and she slipped it into the bosom of her kimono. He watched her curiously, wondering what she did with all the money she secured from him.

All of a sudden she put this question to him, “Sa-ay, how much it taking go to America?”

“How much? Oh, not much. Depends on how you go. Four hundred or five hundred dollars, possibly.”

She groaned. “How much come ad Japan?”

“The same.”

She sighed. “Sa-ay, kind augustness, I lig go ad America. Pray, give me moneys go there.”

“I’ll take you some day, Yuki.”

She retreated before this offer.

“Ah, thangs; yes, some day, of course. Ah–haha–ha–ha–aa. Sa–ay, it taking more moneys than thad three-four hundred dollars, whicheven?”

“Yes; about that much again for incidentals––possibly more.”

She sighed hugely this time, and he knew she was not affecting.

A few days later, poking among her pretty belongings, as he so much liked to do––she was out in the garden gathering flowers for their dinner-table––he found her little jewel-box. Like everything else she possessed it was daintily perfumed with the aroma Japonica. At the top lay the few pieces of jewelry he had bought her on different occasions when he had taken her on trips to the city. He lifted the tray, and then he saw something that startled him. It was a roll of bank-bills. He took it out and counted it. There was not quite one hundred dollars. He calculated all he had given her. It amounted to a little over twice this much. She had been saving, after all. What was her object? he wondered.

Chapter VI.

My Wife

The second time his wife left him Laurin Reynolds was very wretched. He missed her exceedingly, though he would not have admitted it, for he was also very angry with her. When she had gone away that first time so soon after their marriage he had not felt her absence as he did now, for then she had not become a necessity to him. But she had lived with him now two whole months and had become a part of his life. She was not a mere passing fancy, and he knew it was folly to endeavor so to convince himself, as in his resentment at her treatment he was trying to do.

The house was desolate without her. Everywhere there were evidences of the little girl-here a pair of her tiny sandals, some piece of tawdry kanzashi for her hair, her koto, samisen and little drum; in the zashishi, her own little room, and all over the house lingered the faint odor of her favorite perfume, so subtle that it made the man weak.

He grew to hate the silence of the rooms. Their household had always been small, with just a man and a maid to wait on them; and now only one presence gone from it, and yet how painfully quiet the place had grown! He realized what all her little noises had become to him. He stayed outdoors as much as he could, only to return restlessly to the house, with a half hope that perhaps she was hiding somewhere in it and playing some prank on him, as she was fond of doing, bursting out from some unexpected place of hiding. But there was no trace of her anywhere; and when the second day actually passed the realization that she was indeed gone forced itself home to him, leaving him stupid with rage and despair.

He was bitterly angry with her. She had no right to leave him like this without a word of explanation. How was he to know where she had gone or what might happen to her? And the thought of anything dire really overtaking her nearly drove him distracted. He hung around the balconies of the house, wandered down into the garden, and strayed restlessly about; all the time he knew he was waiting for her, and in the waiting doubling his own misery.

She came back in four days, slipped into the house noiselessly and ran up to her room. He heard her, knew she was in the house, but checked his first impulse to go to her, and threw himself back on a couch, where he assumed a careless attitude, though inwardly his mood was a stern, unapproachable and forbidding one.

Suddenly he heard her voice. It came floating down the stairs, every weird minor note thrilling, mocking, fascinating him. “Toko-ton-yare ron-ton-ton!” she sang. Then the voice ceased a moment. He knew that she was waiting for him to call her, but he did not move. He was angry with her and decided he would not forgive her readily.

She began beating on her drum. He understood her object. She was trying to attract him. Suddenly she danced down the stairs and burst in on him.

“Ha-ha-ha-a-a-a!” she laughed.

He ignored her sternly. She ceased her noise and laughter, and approaching him studied him with her head cocked bewitchingly on one side.

“You angry ad me, excellency?” she inquired, with solicitude.

No reply.

“You very mad ad me, augustness?”

Still no reply.

“You very cross ad me, my lord?”

She shouted now, a high, mocking, joyous note in her laughter. “Hah! You very, very, very, very, very offended, Mister Reynolds?”

“It seems to please you,” said Laurin, scathingly, wasting his sarcasm, and turning his eyes from her.

She laughed wickedly. “Ah, tha’s so nize.”

“What is?”

“Thad you loog so angery. My! you loog lig grade big--whad you call thad--toranadodo.” She knew how to pronounce tornado, but wanted to make him laugh. She failed in her purpose, however. She tried another way.

“How you change!” She sighed with beatific delight. Laurin growled.

“Dear me! I thing you grown more nize-loogin’.”

Laurin got up and walked across to the window, turning his back deliberately on her and whistling with forced gaiety, his hands in his pockets. She approached him with feigned timidity and stood at his elbow.

“You glad to see me bag, excellency?”

“No!” shortly.

This emphatic answer frightened her. She was not so sure of him, after all.

“You lig’ me go away?” Her voice was excessively timid now.

“Yes.”

She loitered only a moment, as though waiting for him to speak, and then “Go-o-by,” she said, gently.

He felt, for he would not turn around to see, that she was crossing the room toward the door, slowly, reluctantly. He heard the shoji pushed aside and then shut to. He was alone! He sprang forward and called her name aloud. She came running back to him and plunged into his arms. He held her close, almost fiercely. The anger was all gone. His face was white and drawn. The dread of losing her again had overpowered him. When she tried to extricate herself from his arms he would not let her go. He sat down on one of the chairs and held her on his knees. She was laughing now, laughing and poohing at his white face.

“My grashes!” she said, “you loog lig’ old Chinese priest ad the temple.” She pulled a long face and drew her pretty eyes up high with her finger-tips; then she chanted some solemn text, mocking blasphemously her ancestors’ religion.

But Laurin was grave. He had not the heart to find mirth even in her naughtiness.

“Yuki,” he said, “you must be serious for a moment and listen to me.”

“I listening, Mr. Solemn-Angery-Patch!” She meant crosspatch. “You loog lig”

“Where did you go?”

“Oh, jus’ liddle bid visit.”

“Where did you go?” he repeated, insistently.

“Sa-ay, I forgitting,” she drawled.

“Answer me!”

She pretended to think, and then suddenly remember, sighing hypocritically meanwhile.

“I lig’ forgitting,” she said.

“Forgetting what?”

“Where I been.”

“Why?”

“Tha’s so sad! Alas! I visiting thad ole fadder and mudder, ninety-nine and one hundred years old, and those seventeen liddle brudders and sisters. You missing me very much?” she inquired, archly, seemingly anxious to divert him from the subject of her whereabouts.

“No,” he said, shortly, stung by her falsity.

“I don’ thing!”

“Where were you, Yuki?”

“Now, whad you wan’ know for, sinze you don’ lig’ me?”

“Did I say so?”

“You say you don’ miss.”

“I was a liar,” he said, bitterly. “Where were you?”

“Jus’ over cross street, see my ole frien’s ad tea-garden.”

“I thought you said you were visiting your people?”

She was not at all abashed.

“Sa-ay, firs’ you saying you miss me; then thad you liar. Sa-ay, you big liar; I jus’ liddle bid liar.”

“Yuki, if you leave me like this again you need never come back. Do you understand?”

“Never!”

“I mean that!”

“What you goin’ do? Git you nudder wife?”

He pushed her from him in savage disgust. She laughed with infinite relish. He sat down a little distance from her and put his face wearily between his hands. Yuki regarded him a moment, and then she silently went to him, pulled his hands down and kissed his lips.

“I have missed you terribly,” he said, hoarsely. She was all compunction.

“I very sawry––I din know thad you caring very much for poor liddle me, an’ mebbe I bedder nod come bag ad you.”

“Why did you come, then?” he said, gently.

“I dunno,” she said, forlornly.

After a moment she said, more brightly, “I bringing you something something so nize.”

“What is it, Yuki dear?” He was reluctant to let her go even for a moment.

“Flowers,” she said. He released her and she brought them to him, a huge bunch of cherry-blossoms. She buried her delightful little nose in them. “Ah, tha’s mos’ sweet flowers of all,” she said. “For you, for you, my lord.”

“Where did you get them, dear?” he asked, taking her hands instead of the flowers, and then suddenly drawing her, flowers and all, into his arms.

She faltered a minute, then she said, with the old daring smile flashing back in her face, “Nize Japanese gents made me present those flowers.”

He caught her wrists in a grip of iron. “What do you mean?” he demanded, fiercely, wild jealousy assailing him.

She pulled herself from him and regarded the little wrists ruefully.

“Ain’ you ‘shamed?” she accused.

“Yes.” He kissed the little wrists with an inward sob. “Tell me all, little one! Please don’t hide anything from me! I can’t bear it!”

“Thad Japanese gent wanter marry with me,” she informed him, calmly, smiling and dimpling as if it amused her, and then making a face to show him her feelings in the matter. “My! how he adore me!” she added, vividly.

“Marry with you! What do you mean? You are my wife!”

“Yes, bud he din know thad,” she said, consolingly; “an’ see, I bringing them same flowers ad you.”

He took them from her arms. They were all crushed now, and it distressed her. No Japanese can bear to see a flower abused. She fingered some of the petals sadly; then she sighed, looking up at him with tears in her eyes. “Tha’s mos’ beautiful thing in all the whole worl’,” she said, indicating the flowers; “so pure, so kind, so sweet.”

“I know something more beautiful and sweet and––and pure.”

“Ah, whad?” she said, her face shining, the pupils of the blue eyes so large as to make them look almost black.

“My wife!” he breathed, warmly.

Chapter VII.

A Journey by Night

Every day, all unknown to Yuki, her husband looked into her little jewel-box. The pile of bills grew larger. He no longer refused her requests for money. The last time he had counted her savings there were four hundred dollars. He took a whim to make it five hundred, and that same day gave her a clear one hundred dollars.

She had given him a solemn promise never to leave him again without his consent, and for a whole month she had kept steadfastly at home. It was the happiest month in Laurin’s life, a month that spelt naught else save joy and sunshine. Even a few days’ illness that he had he was glad of, for it was then that he saw another side to his wife’s character. All the old mockery and folly vanished. She was angelic in her sweet solicitude and tenderness. The gentle woman-soul which shone from the now steadfast blue eyes, as she nursed and waited on him, was worth weeks of illness, he thought, and he was angry with himself for so soon recovering It was heaven to be ministered to by Yuki. The fever in his temples cooled as if by magic under the touch of her soothing hands.

But the day after he had given her the hundred dollars she came to him and begged very humbly to be permitted to visit her old father and mother and seventeen little brothers and sisters. She still kept up this deception. He refused her almost gruffly. He had grown selfish and spoiled under her care. All that day, however, he watched her suspiciously, fearful she would go without his consent. And he was right. In the evening he saw her stealing from the house. Laurin took his hat, and keeping at a good distance, but never losing sight of her for a moment, he followed her.

Twilight was falling. Softly, tenderly the darkness swept away the exquisite rays of red and yellow that the departing sun had left behind. Yuki was walking rapidly toward Tokyo. It was not very far to the city, but the thought of her little tender feet treading the way alone unnerved and choked the young man. Whatever her mission, wherever she was going, he would follow her. She belonged to him completely. She should never escape him now, he told himself.

She seemed to know her way, and showed no hesitation or fear when once in Tokyo, but bent her steps quickly and with assurance, turning and returning through the maze of streets until she finally reached the great terminal station at Shimbashi. They had come a long distance. The girl looked tired; there were weary shadows under her eyes as she passed into the railroad inclosure and bought a ticket.

Her husband went to the ticket-window, inquired where the girl was going, and bought a ticket for the same place. Then began the journey in the uncomfortable train. Yuki found a seat, and sat very quietly staring out at the flying darkness. After a time she put her head back against the seat, and despite the jolting of the train fell asleep. Her husband was close to her now in the next seat, in fact. She had not slept more than half an hour when the slowing up of the train awakened her. She came to life with a start, gathered her little belongings together and left the train, her husband still following her.

Yuki had not far to walk. Only a few steps from the little station, and then she was before one of those old-fashioned, pretentious palaces affected by the nobles. There were signs of neglect about the house and gardens, which had fallen out of repair. No retainers or servants were in sight. At the gate she paused a moment, leaning wearily against it, ere she opened it and disappeared into the shadows of the palace. Her husband stood for a long time staring blankly into the gloom. Then very slowly he retraced his steps to the railway-station, bought his ticket and returned to Tokyo. Somehow, he could not have told exactly why, the events of the night had strengthened his belief in her. He felt sure she would return to him.

And she did, hardly two days later. He was very gentle to her this time. There were no more questions asked and she vouchsafed no explanation.

And now she was docile, gentle, very clinging and submissive and loving. He called her his “Undine,” and vowed he had found her soul at last. But once he found her in tears. She protested they had come because she had laughed so hard. Another time when he offered her money she passionately refused to take it. It was the first time since she had lived with him that she had done so. Thereafter she refused to take even the regular weekly allowance of fifteen dollars agreed upon. He looked in the little jewel-box and found her savings were all gone.

Her docility and gentleness confirmed his confidence in her. He was sure she would never leave him again. He even told her of his belief, and she did not deny it. They were like two happy children in these days. They played together like children, and laughed as joyously and willfully.

“I have conquered her––she is coming to care for me––that is it,” said the young man.

“Why are you so good to me, Yuki-san?” he asked her one day when she had sent the maid away and had waited on him at the table with her own hands.

“Jus’ for liddle while,” she answered, softly.

“Little while?” This little pin-prick punctured his happiness and startled him.

“What do you mean?” he demanded, sharply. She could not answer. She put her head down and sobbed of a sudden with pitiful abandon.

“Don’t you care for me, Yuki?” he asked.

At this she threw her arms tightly about his neck and he felt hot tears against his cheeks.

“My lord, I––I lof you!” she cried.

“Then why do you talk about leaving me?”

She sobbed even more violently, but gave him no answer.

After that day she was constantly melancholy till her depression communicated itself to him, and he began to suspect her of once more deceiving him. He spoke to her sharply and watched her constantly and suspiciously.

And then one day he found her clothes neatly packed in a bundle, as though in preparation for a journey, and his wrath burst its bounds. The full sense of her deceit smote and staggered him. Previously she had never taken any of her wardrobe with her. He thought that now she intended leaving him forever. He went to her and upbraided her cruelly. She denied nothing. She did not even trouble to mock or laugh at him; nor did she weep. She was mute, that was all; and he, infuriated, said things which rankled in his conscience for years afterward.

After this time a painful constraint and gloom settled between them. The girl grew white and thin and wistful, the man cynical and restless; and in the midst of their gloom came word from Taro Burton announcing that he had arrived in Tokyo. Laurin rushed off to meet him, telling Yuki he expected an old friend and would bring him home with him that evening.