I was helping Menna one day. He had been very busy, and I had been working for him

both mornings and afternoons. He had told me, however, that soon he expected to

“pick up and go West,” and I was troubled about that. I depended upon

Menna for most of my work, and we got along splendidly together. As I have said,

Menna had always treated me just like a “fellow,” as he would call it.

There was a knock at the door, and in came Paul Bonnat. After nodding to Menna, he

strolled over to where I was working and stood at the back of me watching me

paint.

“She’s quite a painter,” he said after a moment to Menna, who looked up and

nodded, and said:

“Yes, she does quite O.K.”

After a while Menna turned around his stool and asked:

“Got anything on to-night, Bonnat?”

“No—nothing particular.”

“Well, a lady friend of mine is coming in from Staten Island, and I promised to

take her somewhere to supper and see the town. Can’t you and Miss Ascough join

us?”

Bonnat beamed, just as if Menna had handed him a gift, and he said:

“Sure, if Miss Ascough will go with me.”

I said that I would. I think I would have gone with him anywhere he had asked me

to.

“Meet us here at seven, then,” said Menna, returning to his work.

“All right. Good-by.” Bonnat went out slamming the door noisily behind him.

We could hear him singing the Preislied from “Die Meistersinger”

as he went up the stairs. He had a big, wonderful baritone voice. We stopped

painting to listen to him, but when I turned to resume my work, I found Menna

watching me. He said:

“You and Bonnat are getting pretty friendly, eh?”

I felt myself color warmly, but I tried to laugh, and said:

“Oh, no more than I am with any of the other boys.”

Menna had his thumb through his palette, and he stared at me hard. Then he said

quite suddenly:

“Gee! What a fool I was to let him get ahead of me.”

He set down his palette, and came over to my stool:

“Say, Marion” (he had never called me Marion before), “you and I would make

a corking good team. Suppose we pair off together to-night, and we’ll put Miss

Fleming on to Bonnat? What do you say?”

“Mr. Menna, you had better stick to your own girl,” I said, feeling uneasy.

Menna continued to stare down at me, and as he said nothing to that, I added:

“You know you and I are just partners in our work, and don’t let’s fool. It’ll

spoil everything.”

“Oh, all right,” said he. “I don’t have to get down on my knees to you or

any other girl.”

He had never spoken to me like that before. Until this day, he had never asked me

to go anywhere with him, nor tried to see me after work hours; I did not suppose

he was the least bit interested in me, and I imagine he was quite settled with his

own sweetheart. I was so glad when Miss Fleming knocked on the door.

That evening we all went to Stuttgart Hall. It was one of the oldest places in New

York, and was interesting because of the class of people who patronized the place

and its resemblance to the German gardens, which it was in fact itself. There were

German ornaments, and steins all around the place on a high shelf. There was an

excellent orchestra, which played good selections, and Bonnat hummed when they

played some of his favorites. Menna and Bonnat seemed to differ on almost every

subject, and Menna seemed in a savagely contrary mood that night.

Bonnat would explain his point of view about something, and Menna would say

irritably:

“Yes, yes, but what’s the use?”

Bonnat said that a man should show in his work the human mood, and that a picture

should mean something more than a pretty melody of colors. Menna interrupted him

with:

“What the use, so long as we get good Pilsener beer.”

Paul laughed at that, and called to a waiter to bring some more Pilsener for Menna

right away. After the dinner was over, Mr. Menna took Miss Fleming home, and Paul

and I walked across on Fourteenth Street, stopping to look in the windows, and to

glance at the curious people in the throngs that passed us. Fourteenth Street was

then a very gay and bedizened place at night.

When we reached my door, Paul, who had been very silent, took my hand and held it

for some

330time without saying a word. I could feel his eyes looking

down on me in the darkness of the street, and somehow the very clasp of his hand

seemed to be speaking to me, telling me things that made me feel warm, and oh! so

happy. When he did speak at last, his big voice was curiously repressed, and he

said huskily:

“I think I know now why some men give up Art for the sake of protecting their

own!” He said “own” with such strange emphasis, and he

pressed my hand as he said it, that I felt too moved to answer him, and I had a

great longing to put my arms around him and draw his head down to mine.

After that night Mr. Menna did not seem the same to me. All the little kindnesses

I had been accustomed to receive from him, such as cleaning my palette, my

brushes, and nailing my canvases on the stretchers, he now let me do myself, and

once when I asked him to varnish a painting of mine, he answered:

“Why don’t you get that Bonnat to do it for you?”

‘Dear Marion:

‘Mr. Hersh is going to put on the living pictures in Providence for two

weeks, and he says he would like to take the same girls that he had

before, and told me to tell you that he will pay twenty dollars a week.

Also that he will take us to Boston and some other places, if we do well

in Providence.

‘Why don’t you come and see us to-night? and bring along the fellow Hatty

said she saw you walking with on Fourteenth St. How are you, anyway? I’m

leaving for Providence tomorrow.

With love,

LIL.’

I had been thinking of Lil’s letter all day, but I could not make up my mind how

to answer it. The thought of making forty dollars in two weeks appealed to me very

much, for we were not very busy now, and Menna expected to go West very soon. On

account of my work with Menna I had not done much posing in New York, but I

intended to call on some artists and see about engagements when Menna should go.

Forty dollars was a lot of money to me, and it would take me many weeks to earn

that much in posing. It did seem as if I simply could not refuse this chance. But

my mind kept turning to Paul Bonnat. I could think of nobody else but him. He had

made my life worth while. I thought of all the happy times we had had together. He

did not take me to expensive places as Reggie used to, but he lived as I did, and

we enjoyed the same things—that Reggie would have called silly and cheap. We went

to the exhibitions of the artists, long walks in the Park, to the Metropolitan

Museum, and, best of all, to the Opera. That was the one thing Paul would be

extravagant about, although our seats were in the top gallery of the family

circle. I would be out of breath by the time I climbed up there, but I learned to

appreciate and love only the best in music, just as Paul was teaching me to

understand the best in all art.

There I listened with mingled feeling and enjoyment to the operas of Wagner. His

“Tristan und Isolde” rang in my ears for days, and by the time I heard

“Die Meistersinger” I was able thoroughly to enjoy what before had been an

unknown land. We Canadians had never gone much beyond a little of Mendelssohn,

which the teachers of music seemed to consider the height of classical music, and

the people were still singing the old sentimental songs, not the ragtime the

Americans love, but the deadly sweet melodies that cloy and teach one nothing. Of

course, no doubt things have changed there now; but it was that way when I was a

girl in Montreal.

I did not want to leave New York even for two weeks. I had begun to love my life

here. There was something fine in that comradeship with the boys in the ramshackle

studio building. I had been accepted as one of the crowd, and I knew it was

Bonnat’s influence that made them all treat me as a sister. Fisher once said that

a “fellow would think twice before he said anything to me that wasn’t straight

goods,” and he added, “Bonnat’s so darned big, you

know.”

I had often cooked for all the boys in the building. We would have what they

called a “spread” in Bonnat’s or Fisher’s studio, and they would all come

flocking in, and fall to greedily upon the good things I had cooked. I felt a

motherly impulse toward them all, and I wanted to care for and cook for—yes—and

wash them, too. Some of the artists in that building were pretty

dirty. Paul had never spoken of love to me, and I was afraid to analyze my

feelings for him. Reggie’s letters were still pouring in upon me and they still

harped upon one thing—my running away from him in Boston. He kept urging me to

come home, and lately he had even hinted that he was coming again to fetch me; but

he said he would not tell me when he would come, in case I should run off

again.

I used to sit reading Reggie’s letters with the queerest sort of feeling, for, as

I read, I would not see Reggie in my mind at all, but Paul Bonnat! It did seem

that all the things that Reggie said which once would have pierced and hurt me

cruelly now seemed to have lost their power. I had even a tolerant sort of pity

for Reggie, and wondered why he should trouble any longer to accuse me of this or

that, or even to write to me at all. I am sure I should not have greatly cared if

his letters had ceased to come. And now, as I turned over in my mind the question

of leaving New York, I thought not only of Reggie, but of Paul. It is true, I

might only be away for the two weeks in Providence; on the other hand I realized

that I would be foolish not to go on with the troupe to Boston. I decided finally

that I would go.

338

I went over especially to tell Paul about it. I said:

“Mr. Bonnat, I’m going away from New York, to do some more of that—that

living-picture work.” I waited a moment to see what he would say—he had not

turned around—and then I added, as I wanted to see if he really cared—“Maybe I

won’t come back at all.”

He stood up, and took me by the shoulders, making me look straight at him.

“How long are you to be gone?” he demanded, as if he had penetrated my

ruse.

“Two weeks in Providence,” I said, “but if we succeed, we go on to Boston

and—”

“Promise me you’ll come back in two weeks. Promise me that,” he said.

He was looking straight down into my eyes, and I think I would have promised him

anything he asked me to do; so I said, in a little weak voice:

“I promise.”

“Good!” he replied. “I would not let you go, if it were in my power to stop

you, but I know you need the money, and I have no right to deprive you of it.

Good gad! It’s tough not to be able to—” He broke off, and gently took my

hands in his.

“Look here, little mouse. There’s a chance of my being able to make a big pot of

money. I’ll know in a few days’ time. Then you shall not have to worry about

anything. But as I am now fixed, why I can’t stop you from anything. I haven’t

the right.”

“Oh, I’ll be back soon, and if you like you can see me off on the train.”

When we were at the Grand Central the following night I tried to appear cheerful,

but I could not prevent the tears running down my face, and when he finally took

my hand to say good-by I said:

“Oh, it’s dreadful for me to say this: b-but if I don’t see you soon again, I-I

t-think I shall die!”

He bent down when I said that and kissed me right on my lips, and he did not seem

to care whether everyone in the station saw us or not. Then I knew that he did

love me, and that knowledge sent me flying blindly down the platform. After I was

aboard, I found I had taken the wrong train to Providence. I should have taken an

earlier or a later one. Lil was already there, and was to have met me at the

station, but the train I had taken would not get in till four in the morning.

When I arrived in Providence I did not know where to go. I had Lil’s address, but

she had written me when she was living at a “very respectable house,” where

the people would have been terribly shocked to know she was a model, and I felt I

could not go there at such an hour in the morning. The rain was coming down in

torrents. A colored boy was carrying my bag, and he asked me where I wanted to go.

Indeed I did not know. When I hesitated, he said that the hotels didn’t take

ladies alone, but that he knew of an all-night restaurant, where I could get

something hot to eat and I could stay there till morning. So he took me over to

Mink’s. I had often eaten in Mink’s restaurant in Boston, and the place looked

quite familiar to me. I had a cup of hot coffee and a sandwich, and then I asked

the waitress if there was some place where I could go and freshen or clean up a

bit. She whispered to the man at the desk, and he nodded, and then she beckoned to

me to follow her. We went upstairs to a sort of loft. It was bare, save of packing

cases, but she showed me a little, cracked looking glass, where she said I could

do my hair. I told her I had been on the train all night, and she said

sympathetically:

“Sure, you look it.”

I went over to Lil’s boarding house about seven in the morning. She was right near

Mink’s, and said I was foolish not to have come right over.

Well, we played every night in the theater in Providence, and we made what

theatrical people call a “hit.” The whole town turned out to see us. The

girls were all as pleased as could be, and so was Mr. Hersh, and they made all

kinds of plans for the road tour, but I could think of nothing but New York, and I

was so lonely, in spite of the noisy company of the girls, that I used to go over

and look at the railway tracks that I knew ran clear to New York. And I thought of

Paul! I thought of Paul every single minute. The little maid would slip his

letters every morning under my door, and I used to cry and laugh before I even

opened them and I held them to my lips and face, and I kept them all in the bosom

of my dress, right next to me.

We had finished our engagement. Lil and I were coming out of the dressing-room the

last night, when somebody slapped me on the back. I turned around, and there was

Mr. Davis; he was so glad to see me that he nearly wrung my hand off, and he

insisted on walking home with us. He told me he was now manager of a theatrical

company, and that he had been looking around for me

ever

since Lil told him I was in New York.

“Now, Marion,” he said, “you are going to begin where you left off in

Montreal, and it’s up to you to make good. You’ve got it in you, and I want to

prove it.”

I asked him what he meant, and he said he was starting a new “show” in Boston

that week, and that he had a part for me that would give me an opportunity.

I said faintly: “I was going back to New York to-morrow.”

Lil exclaimed: “What’re you talking about? Aren’t you going with Mr.

Hersh?”

“Instead of going to New York,” said Mr. Davis, “you come along with me to

Boston. Cut out this living-picture stuff. It’s not worthy of you. I always

said there was the right stuff in you, Marion, and now I’m going to give you

the chance to prove it.”

For a moment an old vision came back to me. I saw myself as Camille,

the part I had so loved when little more than a child in Montreal, and I felt

again the sway of old ambitions. I said to Mr. Davis:

“Oh yes, I think I will go with you!”

But when I got back to my room I took out Paul’s last letter. How confident he was

of my keeping my promise to return. He wrote of all the preparations he was

making, and he said he had a stroke of luck, and that I should share it with him.

We would have dinner at Mouquin’s, and then we would see some show, or the opera.

Whatever we did, or wherever we went, we would be together.

I got out my little writing-pad, and I wrote a letter hurriedly to Mr. Davis:

‘Will you please excuse me, but I have to go to New York. I’ll let you

know later about acting.’

I sent the note to Mr. Davis by the little maid in the house, and he sent back a

sheet with this laconic message upon it:

“Now or never—Give you till morning.”

Lil talked and talked and talked to me all night about it, and she seemed to think

I was crazy not to grab this chance that had come to me, and she said any one of

the other girls would have gone clean daft about it. She said I was a little fool,

and never knew when opportunity come in my way. “Just look,” she said, “how

you turned down that chance you had to be a show-girl, and all of us other

girls weren’t even asked, and I’ll bet our legs are as pretty as yours. It’s

just because you’ve got a sort of—of—well, I heard a man call it sex-appeal

about you, but you’re foolish to throw away your good chances, and by-and-by

they won’t come to you. You’ll get fat and ugly.”

I said: “Oh, Lil, stop it. I guess I know my business better than you.”

“Well, then, answer me this,” said Lil, sitting up in bed: “Are you engaged

to that fellow who sends you letters every day?”

I could not answer her.

“Well, what about Reggie Bertie?”

“For heaven’s sake, go to sleep,” I entreated her, and with a grunt of

disgust she at last turned over.

Next morning Paul’s letter fully decided me. It said that he would be at the

station to meet me! He was expecting me, and I must not, on any account, fail

him.

“Lil, wake up! Wake up!” I cried, shaking her by the arm. “I’m going to

take the first train back to New York.”

Lil answered sleepily: “Marion, you always were crazy.”

All of a sudden the room turned red on all sides of us, and I realized that it was

on fire. The little stove had a pipe with an elbow in the wall, and when I put a

match to the kindling, the flames must have crept up to the thin wooden walls from

the elbow, and in an instant the wall had ignited. I had on only a night-dress. I

seized the quilt off the bed, and threw it on the flames, but it seemed only to

serve as fresh fuel. Lil was crouched back on the bed, petrified with

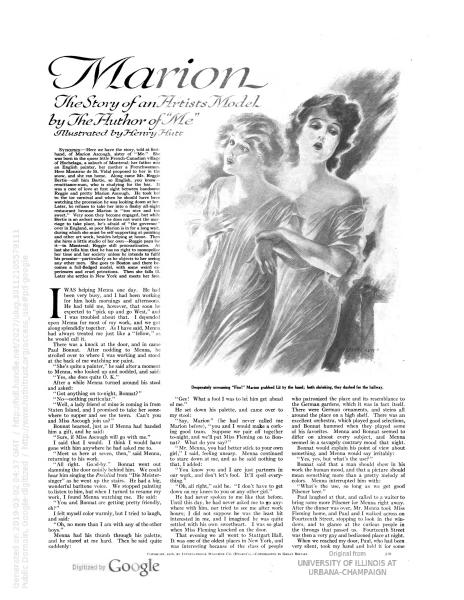

339terror, and literally unable to move. Desperately screaming:

“Fire, fire!” I seized the pitcher and flung it at the flames, and then

somehow I grabbed hold of Lil by the hand, and both shrieking, we ran out into the

hall. Then I fainted. When I came to, the fire was out and the landlady and her

son and husband and Lil were all standing over me laughing and crying.

“Well,” said the man, “did you try to burn us out?” He turned to his

wife and asked: “It’s a good job we’re insured, eh?” My clothes were not

burned, but soaking wet, and so I missed my train that Paul was going to meet.

Oh, how good it was to enter New York once more! I remembered how ugly the city

had looked to me that first time when I had come from Boston. Now even the rows of

flat houses and dingy tall buildings seemed to take on a sturdy and friendly

beauty.

Paul was walking up and down the station, and he came rushing up to me as I came

through the gates. He was pale, and even seemed to tremble, as he caught me by the

arm and cried:

“When you did not come on that train, I was afraid you had changed your mind,

and were not coming back to me. I’ve been waiting here all day, watching each

train that arrived from Providence. Oh, sweetheart, I’ve been nearly

crazy!”

I told him about the fire, and he seized hold of my hands, and examined them.

“Don’t tell me you hurt yourself!” he cried, and when I reassured him, it was

all I could do to keep him from hugging me right there in the station. All the way

on the car he held my hand, and although he did not say anything at all to me, I

knew just what was in his heart. He loved me, and nothing else in all the whole

wide world mattered.

He had helped me out at the Studio Building, and now as I went up the old rickety

stairs, I realized that this was my home!

It was a ramshackle, very old, neglected, rickety sort of place, and I do not know

why they called it Paresis Row. The name did not sound ugly to me, somehow. I

loved everything about the place, even the queer businesses carried on upon the

lower floors, and old Mary, the slatterny caretaker, who scolded the boys

alternately and then did little kindnesses for them. I remember how once she kept

a creditor away from poor Fisher by waving her broom at him till he fled in

fear.

I laughed, as we went by the door of that crazy old artist that the boys used to

tease by dropping a piece of iron on the floor, after holding it up high. They

would wait a few minutes, and then he would come hobbling up the stairs. There

would be three regular taps, and then he would put his head in and say:

“Gentlemen, methinks I heard a noise!”

On the first floor back a man taught singing, and he had gotten up a class of

policemen. It seemed as if they sang forever the chorus of a song that went like

this:

“Don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid, don’t be a-f-r-a-i-d!”

Paul opened the door of his studio. The place was all cleaned up and new paper was

on the walls. He showed me behind the screen a little gas-stove, pots hanging at

the back of it, and dishes in a little closet. Then, taking me by the hand, he

opened a door, and showed me a little room adjoining his studio. It seemed to me

lovely. It was papered in soft gray, and the curtains of yellow cheesecloth gave

an appearance of sunlight to it. There were several pieces of new furniture in the

room, and a little Mission dresser. Paul opened the drawers, and rather shyly

showed me some sheets, pillow-slips and towels, which he said he had purchased

for me, and added: “I hope they are all right. I don’t know much about such

things.”

I knew then that Paul intended the room to be for me. He had only the one studio

room before.

“Well, little mouse,” he said, “are you afraid to live with a poor beggar,

or do you love me enough to take the chance?”

Thoughts were rushing through my mind. Memories of conversations and stories among

the artists, on the marriage question, by some considered unnecessary, and somehow

with Paul it seemed right and natural, and the primitive women in me answered:

“Why not? Others have lived with the man they loved without marriage. Why

should not I?” He was waiting for me to speak. I put my hands on his

shoulders, and said:

“Oh, yes, Paul, I will come to you! I will.” A little later, I said:

“Now I must go over to my old room, and have my trunk and some other things I

left there brought over, and I must tell Mrs. Whitehouse, the landlady, as she

expects me back to-day.”

“Well, don’t be long,” said Paul. “I’m afraid you will slip through my arms

just as I have found you.” Mrs. Whitehouse, the landlady, met me at the

door. I told her I was going to move over to Fourteenth Street, to Paresis Row.

She threw up her hands and exclaimed:

“Land sakes! That is no place for a girl to live, and I have no use for them

artists. They are a half-crazy lot, and never have a cent to bless themselves

with. If I were a young and pretty girl like you, Miss Ascough, I would not

waste my time on the likes of them. Now there’s been a fine looking gent

calling for you the last two days, and I told him you’d be back to-day. He’s a

real swell, and if you’d take my advice, you’d get right next to him.”

Even as she spoke the front bell rang. She opened the door, and there was Reggie!

I was standing at the bottom of the stairs, but when I saw him, I fled into the

parlor. He came after me, with his arms outstretched, I found myself staring

across at him, as if I were looking at a stranger.

“Marion” he cried, “I’ve come to bring you home.” I backed away from

him.

“No, no, Reggie, I don’t want you to touch me,” I said. “Go away! I tell

you, go away!”

“You don’t understand,” said Reggie. “I’ve come to take you home. You’ve

won out, Marion, I’m going to marry you!”

He looked as if he were conferring a kingdom on me.

“Listen to me, Reggie,” I said. “I can never, never be your wife

now.”

“Why not? What have you done?” His old anger and suspicion were mounting. He

was looking at me lovingly, half furiously.

“I’ve done nothing—nothing—but I cannot be your wife.”

“If you mean because of Boston—I’ve forgiven everything. I fought it all out in

Montreal and I made up my mind that I had to have you. So I’m going to

marry you, darling. Don’t you understand?”

Further and further away I had backed from him, but now he was right before me. I

looked up at Reggie, but a vision arose between us—Paul Bonnat’s face. Paul, who

was waiting for me, who had offered to share his all for me, and somehow it seemed

to me more immoral to marry Reggie than to live with the man I loved.

“Reggie Bertie,” I said; “it’s you who don’t understand. I can never be

your wife—because—” Oh, it was very hard to drive that look of love and

longing from Reggie’s face. Once I had loved him, and, although he had hurt me so

cruelly in the past, in that moment I longed to spare him the pain that was to be

his now.

“Well? What is it, Marion? What have you done?”

“Reggie, it’s this: I no longer love you!”

There was a silence, and then he said with an uneasy laugh: “You don’t mean

that. You are angry with me. I’ll soon make you love me again, as you did once,

Marion. You’ll do it when you are my wife.”

“No—no—I never will,” I said steadily, “because—because—there’s another

reason, Reggie. There’s someone else, someone who loves me, and whom I

adore!”

I hope I may never see a man look like Reggie did then. He had turned gray, even

to his lips. He just stared at me, and I think the truth of what I had said slowly

sank in upon him. He drew back.

“I hope you’ll be happy!” he said, and I replied: “Oh, I hope you will be,

too.”

I followed him to the door and he kept on staring at me with that dazed and

incredulous look. Then he went out and closed the door forever on Reggie

Bertie.

The expressman had just put my trunk in the studio. I opened the door of the

little room that Paul had fixed up for me.

“Are you afraid, darling?” he asked. “Are you going to regret giving

yourself to a poor devil like me?” I answered him as steadily as my voice

would let me, for I was trembling.

“I am yours as long as you love me, Paul.” I had started to remove my

hat.

“Not yet, darling,” said Paul, and he took me by the arm and guided me toward

the door. “First we have to go to the Little Church Around the Corner.”

THE END