I had received, of course, a great many letters from Reggie, and I wrote to him

every day. He expected to return in the fall, and he wrote that he was counting

the days. He said very little in his letters about his people, though he must have

known I was anxiously awaiting word as to how they had taken the news of our

engagement.

Toward the end of summer his letters came less frequently, and to my great misery

two weeks passed away when I had no word from him at all. I was feeling blue and

heartsick and, but for my work at the Château, I think I would have done something

desperate. I was really tremendously in love with Reggie and I worried and fretted

over his long absence and silence.

Then one day in late September a messenger boy came with a letter for me. It was

from Reggie. He had returned from his trip, and was back in Montreal. Instead of

being happy to receive his letter, I was filled with resentment and indignation.

He should have come himself and, inspite of what he wrote, I felt I could not

excuse him. This was his letter:

‘Darling Girlie:’

’’I am counting the hours when I will be with you. I tried to get up to

see you last night, but it was impossible. Lord Eaton’s son, young

Albert, was on the steamer coming over, and they are friends of the

governor’s and I simply had to be with them. You see, darling, it means a

good deal to me in the future, to be in touch with these people. His

brother-in-law, whom I met last night, is head-cockalorum in the House of

Parliament, and as I have often told you, my ambition is to get into

politics. It’s the surest high-road to fame for a Barrister.

’’Now I hope my foolish little girl will understand and believe me when I

say that I am thinking for you as much as for myself.

’’I am hungry for a kiss, and I feel I cannot wait till tonight.

Your own,

‘Reggie.’

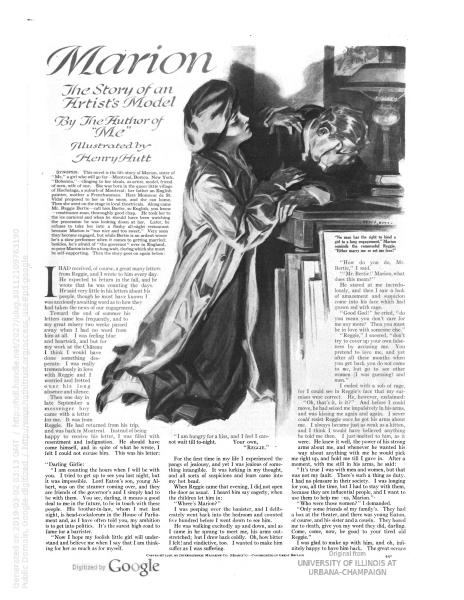

For the first time in my life I experienced the pangs of jealousy, and yet I was

jealous of something intangible. It was lurking in my thought, and all sorts of

suspicions and fears came into my hot head.

When Reggie came that evening, I did not open the door as usual. I heard him say

eagerly, when the children let him in:

“Where’s Marion?”

I was peeping over the banister, and I deliberately went back into the bedroom and

counted five hundred before I went down to see him.

He was walking excitedly up and down, and as I came in he sprang to meet me, his

arms outstretched; but I drew back coldly. Oh, how bitter I felt! and vindictive,

too. I wanted to make him suffer as I was suffering.

“How do you do, Mr. Bertie,” I said.

“‘Mr. Bertie!’ Marion, what does this mean?”

He stared at me incredulously, and then I saw a look of amazement and suspicion

come into his face which had grown suddenly red as with rage.

“Good God!” he cried, “do you mean you don’t care for me any more? Then you

must be in love with someone else.”

“Reggie,” I sneered, “don’t try to cover up your own falseness by accusing

me. You pretend to love me, and yet after all these months when you get back

you do not come to me, but go to see other women (I was guessing)

and men.”

I ended with a sob of rage, for I could see in Reggie’s face that my surmises were

correct. He, however, exclaimed:

“Oh, that’s it, is it?” And before I could move, he had seized me impulsively

in his arms, and was kissing me again and again. I never could resist Reggie once

he got his arms about me. I always became just as weak as a kitten, and I think I

would have believed anything he told me then. I just melted to him, as it were. He

knew it well, the power of his strong arms about me, and whenever he wanted his

way about anything with me he would pick me right up, and hold me till I gave in.

After a moment, with me still in his arms, he said:

“It’s true I was with men and women, but that was not my fault. There’s such a

thing as duty. I had no pleasure in their society. I was longing for you, all

the time, but I had to stay with them, because they are influential people, and

I want to use them to help me—us, Marion.”

“Who were those women?” I demanded.

“Only some friends of my family’s. They had a box at the theatre, and there was

young Eaton, of course, and his sister and a cousin. They bored me to death,

give you my word they did, darling. Come, come now, be good to your tired old

Reggie.”

I was glad to make up with him, and oh, infinitely happy to have him back. The

great oceans

442 of water that had been between us seemed to have melted

away. Nevertheless he had planted a feeling in me that I could not entirely rid

myself of, a feeling of distrust. Like a weed, it was to grow in my heart to

terrible proportions.

The days that followed were happy ones for me. Reggie was with me constantly, and

I even got off several afternoons from the studio and spent the time with him.

One day we made a little trip up the St. Lawrence, Reggie rowing all of the way

from the wharf at Montreal to Boucherville. We started at noon and arrived at six.

There we tied up our boat, and went to look for a place for dinner. We found a

little French hotel and Reggie said to the proprietor:

“We want as good a dinner as you can give us. We’ve rowed all the way from

Montreal and are famished.”

“Bien! You shall have ze turkey which is nearly

cook,’” said the hotel-keeper. “M’sieu he row so far? It is too much. Only

Beeg John, ze Indian, row so far. He go anny deestance. Also he go in his canoe

down those Rapids of Lachine. Vous connais dat

man—Beeg John?”

Yes, we knew about him. Everyone in Montreal did.

We waited on the porch while he prepared our dinner. The last rays of the setting

sun were dropping down in the wood, and away in the distance the reflections upon

the St. Lawrence were turning into dim purple the brilliant orange of a little

while ago. Never have I seen a more beautiful sunset than that over our own St.

Lawrence. I said wistfully:

‘‘Reggie, the sunset makes me think of this poem:

‘‘The sunset gates were opened wide,

Far off in the crimson west,

As through them passed the weary day

In rugged clouds to rest.’’

Before I could finish the last line, Reggie bent over and kissed me right on the

mouth.

“Funny little girl,” he said. “Suppose, instead of quoting poetry you speak

to me, and instead of looking at sunsets, you look at me.”

“Reggie, don’t you like poetry then?”

“It’s all right enough, I suppose, but I’d rather have straight English words.

What’s the sense of muddling one’s language? Silly, I call it,” he said.

I felt disappointed. Our family had always loved poetry. Mama used to read us

Tennyson’s “Idyls of the King,” and we knew all of the characters, and even

played them as children. Moreover, papa and Ada and Charles and even Nora could

all write poetry. Ada made up poems about every little incident in our lives. When

papa went to England, mama would make us little children all kneel down in a row

and repeat a prayer to God that she had made up to send him back soon. Ada wrote a

lovely poem about God hearing us. She also wrote a poem about our Panama hen who

died. She said the wicked Cock Hen (a hen we had that could crow like a cock) had

killed her. How we laughed over that poem. I was sorry Reggie thought it was

nonsense, and I wished he would not laugh or sneer at all the things we did and

liked.

“Dinner is ready pour m’sieu et madame!”

Gracious! That man thought I was Reggie’s wife. I colored to my ears, and I was

glad Reggie did not understand French.

He had set the table for two, and there was a big sixteen pound turkey on it,

smelling so good, and looking brown and delicious. I am sure our Canadian turkeys

are better than any I have ever tasted anywhere else. They certainly are not

“cold-storage birds.”

They charged Reggie for that whole sixteen-pound turkey. He thought it a great

joke, but I wanted to take the rest home. The tide being against us, we left the

rowboat at the hotel, with the instructions to return it, and we took the train

back to Montreal.

Coming home on the train, the conductor proved to be a young man who had gone to

school with me, and he came up with his hand held out:

“Hallo, Marion!”

“Hallo, Jacques.”

I turned to Reggie to introduce him, but Reggie was staring out of the window, and

his chin stuck out as if he were in a bad temper. When Jacques had passed along, I

said crossly to Reggie:

“You needn’t be so rude to my friends, Reggie Bertie.”

“Friends!” he sneered. “My word, Marion, you seem to have a passion for low

company.”

I said:

“Jacques is a nice, honest fellow.”

“No doubt,” said Reggie loftily. “I’ll give him a tip next time he

passes.”

“Oh, how can you be so despicably mean?” I cried.

He turned around in his seat abruptly:

“What in the world has come over you, Marion! You have changed since I came

back.”

I felt the injustice of this, and shut my lips tight. I did not want to quarrel

with Reggie, but I was burning with indignation and I was hurt through and through

by his attitude.

In silence we left the train, and in silence went to my home. At the door Reggie

said:

“We had a pleasant day. Why do you always spoil things so? Good-night.”

I could not speak. I had done nothing, and he made me feel as if I had committed a

crime. The tears ran down my face, and I tried to open the door. Reggie’s arms

came around me from behind, and tilting back my face he kissed me.

“There, there, old girl,” he said, “I’ll forgive you this time, but don’t

let it happen again.”

I had finished the work for the Château de Ramezay, but the Count said I could

stay on there, and that he would try to help me get outside work. He did get me

quite a few orders for work of a kind he himself would not do.

One woman gave me an order to paint pink roses on a green-plush piano cover. She

said her room was all in green and pink. When I had finished the cover, she

ordered a picture

“of the same colors.” She wished me to copy a scene of

mead-

443ows and sheep. So I painted the sunset pink, the meadows

green and the sheep pink. She was delighted and said it was a perfect match to her

carpets.

The Count nearly exploded with delight about it. My orders seemed to give him

exquisite joy, and he sometimes said to see me at work compensated for much and

made life worth while. He used to hover about me, rubbing his hands and chuckling

to himself and muttering: “Ya, ya!”

I did a lot of decorating of boxes for a manufacturer and painted dozens of sofa

pillows. Also I put “real hand-painted” roses on a woman’s ball dress, and

she told me it was the envy of everyone at the big dance at which she wore it.

I did not love these orders, but I made a bit of money, and I needed clothes

badly. It was impossible to go around with Reggie in my thin and shabby things.

Moreover, an especially cold winter had set in, and I did want a new overcoat

badly. I hated to have to wear my old blanket overcoat. It looked so dreadfully

Canadian, and many a time I have seen Reggie look at it askance, though, to do him

justice, he never made any comment about my clothes. In a poor, large family like

ours, there was little enough left for clothes.

About the middle of winter the Count began to have bad spells of melancholia. He

would frighten me by saying:

“Some day ven you come in the morning, you vill find me dead. I am so plue, I

vish I vas dead.”

I tried to laugh at him and cheer him up, but every morning as I came through

those ghostly old halls, I would think of the Count’s words and I would be afraid

to open the door.

One day, about five in the afternoon, when I was getting ready to go, the Count

who, was sitting near the fire, all hunched up, said:

“Please stay mit me a little longer. Come sit by me a little vile. Your radiant

youth vill varm me up.”

I had an engagement with Reggie and was in a hurry to get away. So I said:

“I can’t, Count. I’ve got to run along.”

He stood up suddenly and clicked his heels together.

“Miss Ascough,” he said, “I tink after this you better vork some other

place. You have smiles for all the stupid Canadian boys, but you would not give

to me the leastest.”

“Why, Count,” I said, astonished, “don’t be foolish. I’m in a hurry

to-night, that’s all. I’ve an engagement.”

“Very vell, Miss Ascough. Hurry you out. It is best you come not back

again.”

“Oh, very well!” I said. “Good-by,” and ran down the stairs, feeling

much provoked with the foolish old fellow.

Poor old Count! How I wish I had been kinder and more grateful to him; but in my

egotistical youth I was all incapable of hearing or understanding his pathetic

call for sympathy and companionship. I was flying along through life, as we do in

youth. I was, indeed, as I had said, “in a hurry.”

He died a few years later, in our Montreal, a stranger among strangers, who saw

only in the really beauty-loving soul of the artist the grotesque and queer. I

wished, then, that I could have been with him in the end, but I myself was in a

strange land, and I was experiencing some of the same appalling loneliness that

had so oppressed and crushed my old friend.

When I told Reggie I was not going to the Château any more, he was very thoughtful

for some time. Then he said:

“Why don’t you take a studio up town? You can’t do anything in this God-forsaken

Hochelaga.”

“Why, Reggie,” I said, “you talk as if a studio were to be had for nothing.

Where can I find the money to pay the rent?”

“Look here,” said he, “I’m sure to pass my finals this spring, and I’m

awfully busy. It takes a deuce of a time to get down here. Now, if you had a

studio of your own it would be perfectly proper for me to see you there, and

then besides don’t you see, darling, I would have you all to myself? Here we

are hardly ever alone, unless I take you out.”

“I couldn’t afford to pay for such a place,” I said, sighing, for I would

have loved to have a studio of my own.

“Tell you what you do,” said Reggie. “You let me pay for the room. You

needn’t get an expensive place, you know—just a little studio. Then you tell

your governor that you get the room free for teaching or painting for the

landlady, or something like that. What do you say, darling?”

“I thought you said you despised a liar?” was my answer. “You said you

would never forgive me if I deceived you or told you a lie.”

“But that was to me, darling. That’s different. It’s not lying exactly—just

using a bit of diplomacy, don’t you see?”

“I’m afraid I can’t do it, Reggie. I ought to stay at home. They really need my

help, now Ellen and Charles are both married, and Nellie is engaged and may

marry any time.”

Nellie was the girl next to me. She was engaged to a Frenchman, who was urging her

to marry right away.

“You see,” I went on, “there’s only Ada helping. The other girls are too

young to work yet, though Nora is leaving home next week.”

“Nora! That kid! What on earth is she going to do?”

“Oh, Nora’s not so young. She’s nearly seventeen. You forget we’ve been engaged

some time now, and all the children are growing up.”

I said this sulkily. Secretly I resented Reggie’s constantly putting off our

marriage day.

“But what is she going to do?”

“Oh, she’s going out to the West Indies. She’s got a position on some paper out

there.”

“Whee!” Reggie drew a long whistle.

“West Indies! I’ll be jiggered if your

parents aren’t the easiest ever. Your mother is the last woman in the world to

bring up a family of daughters, and I’m blessed if I ever came460

across any father like yours. Why, do you know when I asked him for his consent

to our engagement, he never asked a single question about myself, but began to

talk about his school days in France, and how he walked, when he was a boy,

from Boulogne to Calais. When I pushed him for an answer, he said absently:

‘Yes, yes, I suppose it’s all right if she wants you,’ and the next moment

asked me if I had read Darwin.”

Reggie laughed heartily at the memory, and then he said:

“Yet I’m fond of your governor, Marion. He is a gentleman.”

“Dear papa,” I said, “wouldn’t hurt a fly, but anybody could cheat him, and

that is why I hate to deceive him.”

Again Reggie burst out laughing, but I would not laugh with him, so he stopped and

said:

“Your mother’s awfully proud of you, darling, and I don’t blame her. She told me

one day that you were the most beautiful baby in England, where she said you

were born. She said she used to take you out to show you off, as you were her

show child. Your mother is a joke, there’s no mistake about that. And to think

you are afraid to leave them to go up-town! Come, come darling, don’t be a

little goose. Think how cosy it will be for us both!”

It would be “cosy.” I realized that, and then the thought of having a studio

all to myself appealed to me. Reggie and I were engaged, and why should I not let

him do a little thing like that to help me. Reggie had never been a very generous

lover. The presents he made me were few and far between, and often I had secretly

compared his affluent appearance with my own shabby self. After all, I could get a

room for a fairly nominal price, and perhaps if I got plenty of work I would soon

be able to pay for it myself. So I agreed to look for a place, much to Reggie’s

delight.

As Reggie had predicted, papa and mama were not particularly interested when I

told them I was going to open a studio up-town, and even when I added that I might

not be able to come home every night, but would sleep sometimes on a lounge in the

studio, mama merely said:

“Well, you must be sure to be home for Sunday dinners anyway.”

Ada, however, looked up sharply and said:

“How much will it cost you?”

I stammered and said I did not know, but that I would get a cheap place. Ada then

said:

“Well, you ought to try and sell papa’s paintings there, too. Nobody wants to

come to Hochelaga to look at them.”

I replied eagerly that I would show papa’s work, and I added that I was going to

try and start a class in painting, too.

“If you make any money,” said Ada, “you ought to help the family, as I have

been doing for some time now, and you are much stronger than I am, and almost

as old.”

Ada had been delicate from a child, and already I was taller and larger than she.

She made up in spirit what she lacked in stature. She was almost fanatically loyal

to mama and the family. She devoted herself to them and tried to imbue in all of

us the same spirit of pride.

Lu Frazer went with me to look for a room. Lu was an Irish-Canadian girl, with

whom I had gone to school. She worked as a stenographer for an insurance firm, and

was very popular with all the girls. There was something about her that made

nearly all the girls go to her and consult her about this or that, and tell her

all about their love affairs.

I had formed the habit of going to Lu about all my worries and anxieties over

Reggie, and I always found a willing listener and staunch champion. The girls

called her the Irish Jew, as she kept a bank account, and whenever the girls were

short of money they would borrow from Lu, who would charge them interest. Reggie

heartily disliked her, without any just reason.

He said:

“She belongs to a class that should by right be scrubbing floors, only she got

some schooling, so she is tickling the typewriter instead.”

Nevertheless I liked Lu, and in spite of Reggie kept her as my friend, though she

knew how he hated her. When I told her about Reggie’s offer to pay for the studio,

she said:

“Um! Then take as fine a one as you can get, Marion. Soak him good and hard. I

hear he pays a great big price for his own rooms at the Windsor.”

I explained to her that I only wanted as cheap a place as I could get, and that as

soon as I made enough money I intended to pay for it myself.

We looked through the advertisements in the papers, made a list and then went

forth to look for that “studio.”

On Victoria Street we found a nice big front parlor, which seemed to be just what

I wanted. The landlady offered it to me for ten dollars a month, and when I said

that that would do nicely, she asked if I were alone, and when I said I was, she

said:

“I hope you work out all day.”

I told her I worked in my room, and that I would make a studio of it. Whereupon

she said:

“I prefer ladies who go out to work. I had one lady here before, and I had to

put her out.”

I looked at Lu, and Lu said:

“We’ll call again.”

“Oh,” said the woman, “if you decide to take the room, I’ll make a

reduction.”

I felt a sort of disgust come over me and, telling her I did not want the room, I

made for the door, hurrying Lu along.

After looking about, we found a back parlor in a French-Canadian family on

University Street. The landlady was very polite, and I paid her eight dollars in

advance.

The following day I moved all my things into the “studio,” as it now, in

fact, began to look like, what with all my paintings about and some of papa’s, an

easel, palette and painting materials. I covered up the ugly couch with some

draperies the Count sent over for me. Poor old fellow, he had sent word to me the

very next day to come back, saying he missed his little pupil very much, but at

Reggie’s advice, I wrote him that I had taken a studio of my own. He then sent me

a lot of draperies and other things, and wrote that he would come to see me very

soon.

I had a sign painted on black japanned tin, with the following inscription:

MISS MARION ASCOUGH

ARTIST

Orders taken for all kinds of work.

I got the landlady to put it in the front window.

The studio was all settled, and I stood to survey my work, a delightful feeling of

proprietorship coming over me. I breathed a sigh of blessed relief to think I was

now free of all home influence, and had a real place all of my own.

“Here is some gentlemens to see mamselle,” called Madame Lavalle, and there

standing in the doorway, smiling at me with a merry twinkle in his eye, was

Colonel Stevens. I had not seen him since that night, nearly four years ago, when

Ellen and I went to ride with him in Mr. Mercier’s carriage. With him now was a

tall man with a very red face and nose. He wore a monocle in his eye, and he was

staring at me through it.

I was very untidy as I had been busy settling up, and my hair was all mussed up

and my hands dirty. I had on my painting apron, and that was smudged over too. I

felt ashamed of my appearance, but Colonel Stevens said:

“Isn’t she cute?”

Then he introduced us. His friend’s name was Davidson.

“We were on our way to the Club,” said the Colonel, “and as we passed your

place I saw your sign, and ‘By Gad,’ I said, ‘I believe that is my little

friend, Marion.’ Now Mr. Davidson is very much interested in art.” He gave a

little wink at Mr. Davidson, and then went on, “and I think he wants to buy some

of your paintings.”

“Oh, sit down,” I urged. Customers at once! I was excited and happy. I pushed

out a big armchair near the fire and Colonel Stevens sat down, and seemed very

much at home. Mr. Davidson followed me to where I had a number of little paintings

on a shelf. I began to show them to him, pointing out the places, but he scarcely

looked at them. Stretching out his hand, he picked up two and said:

“I’ll take these. How much am I to give you?”

“Oh, five—”I began.

“Charge him the full price, Marion,” put in the Colonel. “He’s a rich

dog.”

462

“I get five dollars for two of that size,” I said.

“Well, we’ll turn into ten for each,” smiled Mr. Davidson.

“Oh, that’s too much!” I exclaimed.

“Tut, tut!” said Colonel Stevens, laughing. “They are worth more. She

really is a very clever little girl, eh, Davidson?”

I felt uncomfortable and to cover my confusion I started to wrap the

paintings.

“No, no, don’t bother,” said Mr. Davidson, “leave them here for the

present. I’ll call another time for them. We have to go now.”

When Mr. Davidson shook hands with me he pressed my hand so that I could hardly

pull it away, and just as they were passing out, who should come up the stairs but

Reggie! When he saw Colonel Stevens and Mr. Davidson his face turned perfectly

livid, and he glared at them. The minute the door had closed upon them, he turned

on me:

“What were those men doing here?” he demanded harshly.

My face got hot, and I felt guilty, though of what, I did not know.

“Well? Why don’t you answer me? What was that notorious libertine, Stevens, and

that beast, Davidson, doing here?” he shouted, and then as still I did not

answer him, he yelled: “Why don’t you answer me, instead of standing there and

staring at me, looking your guilt? God in heaven! Have I been a fool about you?

Have you been false to me, then?”

“No, Reggie, indeed I haven’t,” I said. “I didn’t tell you about Ellen and

I going out with him because—because—”

I thought he must have heard of that ride!

“Going out with him! When? Where?”

Suddenly he saw the money in my hand, and the sight of it seemed to drive him

wild.

“What are you doing with that money? Where did you get it from?”

I was holding the two ten-dollar bills all the time in my hand.

“Are you crazy, Reggie?” I cried. “How can you be so silly? This is the

money Mr. Davidson paid me for these paintings.”

“Well, then, what are they doing here if he bought them?” demanded

Reggie.

“He left them here. He said he’d call some other time for them.”

“Marion, are you a fool, or just a deceitful actress? Can’t you see he does not

want your paintings? He gave you that money for expected favors, and, damn it!

I believe you know it, too.”

I went over to Reggie, and somehow, felt older than he. A great pity for him

filled my heart. I put my arms around his neck, and although he tried to push me

from him, I stuck to him and then suddenly, to my surprise, Reggie began to cry.

He had worked himself up to such a state of excitement that he was almost

hysterical. I gathered his head to my breast, and cried with him.

In a little while, we were sitting in the big armchair, and I told Reggie all

about the visit, and also about that ride of long ago—before I had even met

him—that Ellen and I had taken with Colonel Stevens and Mr. Mercier. I think he

was ashamed of himself, but was too stubborn to admit it. Before he left, he made

a parcel of those two paintings, and sent them over, with a bill receipted by me,

to the St. James Club.

It was snowing hard. The snow was coming down in great big flakes. I had built a

big fire in my grate and had turned off all the gas lights. The flames from the

grate threw their glare upon the walls. I was waiting for Reggie, and I was

wondering where I was going to get some money to pay for clothes I badly needed

now, for most of the little I had been earning I had been obliged to send most of

it home. It seemed to me as if every time Ada came to see me it was as a sort of

collector. Help was needed at home, and Ada was going to see that we did our

share.

I had had my studio now nearly a year, and I had made very little money. Reggie

had paid the rent each month, but I had never taken any other help from Reggie. He

seemed to have so much money to spend, and yet he was always saying he was too

poor to marry, though he had passed his examinations and was a full partner in the

big law firm. He said he wanted to build up a good practice before we married.

I heard his footsteps in the hall and the door opened.

“Hallo, hallo! Sitting all alone in the dark, darling?”

Reggie came happily into the studio. He was in evening dress, with his rich

fur-lined coat thrown open. He sat down on the arm of my chair.

“I’m awfully disappointed, darling,” he said. “I had been looking forward

to spending the evening here by the fire with you, but I’m obliged to go with

my partners and a party of friends to a dinner they are giving, and I expect to

meet that member of Parliament I told you about. If I can break away early,

I’ll come back here and say good-night to the sweetest girl in the world. So

don’t go home to-night, as we can have a few moments together anyway.”

I was left once more alone. I sat there staring into the fire. Why did Reggie

never take me to these dinners? There were always women there. Why was I not

introduced to his friends? Why did he leave me more and more alone like this? He

was jealous of every man who spoke to me, and yet he left me alone and went to

dinners and parties where he did not think I was good enough to go.

Someone was rapping on the door, and I called: “Come!” It was Lu Frazer.

“Why, Marion Ascough, what are you sitting alone in the dark for? Where is the

fair one of the golden locks?”

Lu was shaking the snow from her clothes, but she stopped suddenly when she saw my

face.

“What are you crying about?”

“I’m not crying. I’m just yawning.” Lu put her hands on my shoulders.

“What’s his nibs been saying to you now?” she asked.

I shook my head. Somehow I didn’t feel like confiding even in Lu this night.

“Look here, Marion,” she said, “I met an old admirer of yours as I came

here to-night, and he asked me to try and get you to go with him and a friend

to a little supper. He said you knew his friend—that he’d bought some pictures

from you. His name’s Davidson. I told Colonel Stevens I’d do what I could. Now,

I saw that Bertie getting into a sleigh all rigged up in evening clothes and

with that Mrs. Marbridge and her sister. Folks are saying he’s paying attention

to the latter lady. I said to myself, when I saw him: ‘What’s sauce for the

goose is sauce for the gander.’ Marion, you’re a fool to sit moping here, while

he is enjoying himself with his fine society people.”

I jumped to my feet. “I’ll go with you, Lu—anywhere. I’m crazy to go with you.

Let’s hurry up.”

“All right, get dressed while I ’phone the Colonel. He said he’d be waiting at

the St. James Club for an answer for the next half-hour.”

I have a very dim remembrance of that evening. We were in some restaurant, and the

drink was cold and yet it burned my throat like fire. I had never tasted any

liquor before, except the light wine that the Count sometimes sparingly gave me. I

heard someone saying—I think it was Mr. Davidson:

“She’s a hell of a girl to take out for a good time.”

I said I felt ill, and Lu took me out to get the air. She said she would be back

soon. But once out there, I conceived a passionate desire to return to my room and

I ran away in the street from Lu.

As I opened my door a feeling of calamity seemed to come over me. It must have

been nearly twelve o’clock, and I had never been out so late before, not even with

Reggie.

As I came in, Reggie, who had been sitting by the table, stood up. He stared at me

for a long time without saying a word. Then:

“You’ve been out with men!” he said.

“Yes,” I returned defiantly, “I have.”

“And you’ve been drinking!”

“Yes,” I said. “So have you.”

He flung me from him, and then all of a sudden he threw himself down in the chair

by the table and putting his head upon his arms he shook with sobs. All of my

anger melted away and I knelt down beside him and entreated him to forgive me. I

told him just where I had been and with whom, and I said that it was all because I

was tired, tired of waiting so long for him. I said:

“Reggie, no man has a right to bind a girl to a long engagement like this.

Either marry me, or set me free. I am wasting my life for you.”

He said if we were to be married now, his whole future would be ruined, that he

expected to be nominated to a high political position, and to marry at this stage

of his career would be sheer madness.

I promised to wait for Reggie one more year; but I was unhappy—very, very

unhappy.