The debate is lively: Who wrote “Me,” that excellent story? And right into

the midst of the discussion comes a second challenge, a new novel by the same

author—“Marion.” Here’s the challenge: You couldn’t place “Me”; can

you place my sister “Marion”? This is more than “the story of an artist’s

model.” It is an intimate chronicle of the heartaches, the problems of life

and love, of a young French-Canadian girl, who hears the call of art and forsakes

home and native land to follow it. Instead of becoming an actress or a painter she

is forced by dire necessity to earn a living as a model for other more successful

artists. Her struggles, her many adventures in “Bohemian” life, told in the

gripping language of a gifted, experienced author—they are “Marion.” This new

novel by the author of “Me” will only serve to enhance further the deserved

repute of the anonymous writer, who chose to strike out along new lines unhampered

by a literary reputation. “Marion” will increase the desire of many thousands

to answer the question, “Who is the Author of ‘Me’?”

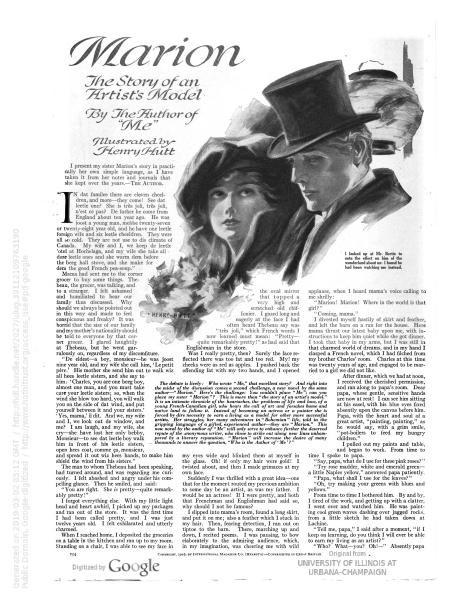

I present my sister Marion’s story in practically her own simple language, as I

have taken it from her notes and journals that she kept over the years.—The

Author.

“In dat familee there are eleven cheeldren, and more—they come! See dat leetle

one? She is très joli, très joli, n’est ce pas? De father he come from England

about ten year ago. He was joost a young man, mebbe twenty-seven or

twenty-eight year old, and he have one leetle foreign wife and six leetle

cheeldren. They were all so cold. They are not use to dis climate of Canada. My

wife and I, we keep de leetle ‘otel at Hochelaga, and my wife she take all dose

leetle ones and she warm dem before the beeg hall stove, and she make for dem

the good French pea-soup.”

Mama had sent me to the corner grocer to buy some things. Thebeau, the grocer, was

talking, and to a stranger. I felt ashamed and humiliated to hear our family thus

discussed. Why should we always be pointed out in this way and made to feel

conspicuous and freaky? It was horrid that the size of our family and my mother’s

nationality should be told to everyone by that corner grocer. I glared haughtily

at Thebeau, but he went garrulously on, regardless of my discomfiture.

“De eldest—a boy, monsieur, he was joost nine year old, and my wife she call

him, ‘Le petit père.’ His mother she send him out to walk wiz all hees leetle

sisters, and she say to him: ‘Charles, you are one beeg boy, almost one man,

and you must take care your leetle sisters; so, when the wind she blow too

hard, you will walk you on the side of dat wind, and put yourself between it

and your sisters.’”

“‘Yes, mama,’ il dit. And we, my wife and I, we

look out de window, and me? I am laugh, and my wife, she cry—she have lost her

only bebby, Monsieur—to see dat leetle boy

walk him in front of his leetle sisters, open hees coat, comme ça, monsieur, and spread

it out wiz hees hands, to make him shield the wind from his sisters.”

The man to whom Thebeau had been speaking, had turned around, and was regarding me

curiously. I felt abashed and angry under his compelling glance. Then he smiled,

and said:

“You are right. She is pretty—quite remarkably pretty!”

I forgot everything else. With my little light head and heart awhirl, I picked up

my packages and ran out of the store. It was the first time I had been called

pretty, and I was just twelve years old. I felt exhilarated and utterly

charmed.

When I reached home, I deposited the groceries on a table in the kitchen and ran

up to my room. Standing on a chair, I was able to see my face in the oval mirror

that topped a very high and scratched old chiffonier. I gazed long and eagerly at the face I had often heard

Thebeau say was “très joli,” which French

words I now learned must mean: “Pretty—quite remarkably pretty!” as had said

that Englishman in the store.

Was I really pretty, then? Surely the face reflected there was too fat and too

red. My! my cheeks were as red as apples. I pushed back the offending fat with my

two hands, and I opened my eyes wide and blinked them at myself in the glass. Oh!

if only my hair were gold! I twisted about, and then I made grimaces at my own

face.

Suddenly I was thrilled with a great idea—one that for the moment routed my

previous ambition to some day be an artist, as was my father. I would be an

actress! If I were pretty, and both that Frenchman and Englishman had said so, why

should I not be famous?

I slipped into mama’s room, found a long skirt, and put it on me; also a feather

which I stuck in my hair. Then, fearing detection, I ran out on tiptoe to the

barn. There, marching up and down, I recited poems. I was pausing, to bow

elaborately to the admiring audience, which, in my imagination, was cheering me

with wild applause, when I heard mama’s voice calling to me shrilly:

“Marion! Marion! Where in the world is that girl?”

“Coming, mama.”

I divested myself hastily of skirt and feather, and left the barn on a run for the

house. Here mama thrust our latest baby upon me, with instructions to keep him

quiet while she got dinner. I took that baby in my arms, but I was still in that

charmed world of dreams, and in my hand I clasped a French novel, which I had

filched from my brother Charles’ room. Charles at this time was twenty years of

age, and engaged to be married to a girl we did not like.

After dinner, which we had at noon, I received the cherished permission, and ran

along to papa’s room. Dear papa, whose gentle, sensitive hands are now at rest! I

can see him sitting at his easel, with his blue eyes fixed absently upon the

canvas before him. Papa, with the heart and soul of a great artist, “painting,

painting,” as he would say, with a grim smile, “pot-boilers to feed my

hungry children.”

I pulled out my paints and table, and began to work. From time to time I spoke to

papa.

“Say, papa, what do I use for these pink roses?”

“Try rose madder, white and emerald green—a little Naples yellow,” answered

papa patiently.

“Papa, what shall I use for the leaves?”

“Oh, try making your greens with blues and yellows.”

From time to time I bothered him. By and by, I tired of the work, and getting up

with a clatter, I went over and watched him. He was painting cool green waves

dashing over jagged rocks, from a little sketch he had taken down at Lachine.

“Tell me, papa,” I said after a moment, “if I keep on learning, do you

think I will ever be able to earn my living as an artist?”

“Who? What—you? Oh!—” Absently papa

255blew the smoke about his

head, gazed at me, but did not seem to see me. He seemed to be talking rather to

himself, not bitterly, but just sadly:

“Better be a dressmaker, or a plumber, or

a butcher, or a policeman. There is no money in art!”

Next to our garden, separated only by a wooden fence, through which we children

used to peep, was the opulent and well-kept garden of Monsieur Prefontaine, who was a very important man, once Mayor of

Hochelaga, the French quarter of Montreal, in which we lived. Madame Prefontaine,

moreover, was an object of unfailing interest and absorbing wonder to us children.

She was an enormously fat woman, and had once taken a trip to New York City, to

look for a wayward sister. There she had been offered a job as fat woman for a big

circus, Madame Prefontaine used to say to the neighbors, who always listened to

her with great respect:

“Mon Dieu! That New York—it is one beeg hell!

Never do I feel so hot as in dat terreeble city! I feel de grease it run all

out of me! Mebbe, eef I stay at dat New York, I may be one beeg

meelionaire—Oui! But, non! Me? I prefer my leetle home, so cool and quiet,

in Hochelaga than be meelionaire in dat New York, dat is like

purgatory.”

We had an old, straggly garden. Everything about it looked “seedy” and

uncared for and wild, for we could not afford a gardener. My sisters and I found

small consolation in papa’s stout assertion that it looked picturesque, with its

gnarled old apple-trees and shrubs in their natural wild state. I was sensitive

about that garden. It was awfully poor looking, in comparison with our neighbors’

nicely kept places. It was just like our family, I sometimes treacherously

thought—unkempt and wild and “heathenish.” A neighbor once called us that. I

stuck out my tongue at her when she said it. Being just next to the fine garden of

Monsieur Prefontaine, it appeared the more

ragged and beggarly, that garden of ours.

Mama would send us children to pick the maggots off the currant bushes and the

bugs off the potato plants and, to encourage us, she would give us one cent for

every pint of bugs or maggots we showed her. I hated the bugs and maggots, but it

was fascinating to dig up the potatoes. To see the vegetables actually under the

earth seemed almost like a miracle, and I would pretend the gnomes and fairies put

them there, and hid inside the potatoes. I once told this to my little brothers

and sisters, and Nora, who was just a little tot, wouldn’t eat a potato again for

weeks, for fear she might bite on a fairy. Most of all, I loved to pick

strawberries, and it was a matter of real grief and humiliation to me that our own

strawberries were so dried-up looking and small, as compared with the big,

luscious berries I knew were in the garden of Monsieur Prefontaine.

On that day I had been picking strawberries for some time, and the sun was hot and

my basket only half full. I kept thinking of the berries in the garden adjoining,

and the more I thought of them, the more I wished I had some of them.

It was very quiet in our garden. Not a sound was anywhere, except the breezes,

making all kinds of mysterious whispers among the leaves. For some time my eye had

become fixed, fascinated, upon a loose board, with a hole in it near the ground. I

looked and looked at that hole, I thought to myself: “It is just about big

enough for me to crawl through.” Hardly had that thought occurred to me,

when down on hands and knees I dropped, and into the garden of the great Monsieur

Prefontaine I crawled.

The strawberry beds were right by the fence. Greedily I fell upon them. Oh, the

exquisite joy of eating forbidden fruit! The fearful thrills that even as I ate

ran up and down my spine, as I glanced about me on all sides. There was even a

wicked feeling of fierce joy in acknowledging to myself that I was a thief.

“Thou shalt not steal!” I repeated the commandment that I had broken even

while my mouth was full, and then, all of a sudden, I heard a voice, one that had

inspired me always with feelings of respect, and awe, and fear.

“How you get in here?”

Monsieur Prefontaine was towering sternly above

me. He was a big man, bearded, and with a face of preternatural importance and

sternness.

I got up. My legs were shaky, and the world was whirling about me. I thought of

the jail, where thieves were taken, and a great terror seized me. Monsieur Prefontaine had been the Mayor of Hochelaga.

He could have put me in prison for all the rest of my life. We would all be

disgraced.

“Well? Well? How you get in here?” demanded Monsieur Prefontaine.

“M’sieu? I—I—crawled in!” I stammered, indicating the hole in

the fence.

“Bien! Crawl out, madame!”

“Madame” to me, who was but twelve years

old!

“CRAWL OUT!” commanded Monsieur, pointing to

the hole, and feeling like a worm, ignominiously, under the awful eye of that

ex-Mayor of Hochelaga, on hands and knees and stomach, I crawled out.

Once on our side, I felt not the shame of being a thief so much, as the

degradation of crawling out with that man looking.

Feeling like a desperate criminal, I swaggered up to the house, swinging my

half-filled basket of strawberries. As I came up the path, Ellen, a sister just

two years older than I, put her head out of an upper window and called down to

me:

“Marion, there’s a beggar boy coming in at the 256 gate. Give him some

of that stale bread mama left on the kitchen table to make a pudding

with.”

The boy was about thirteen, and he was a very dirty boy, with hardly any clothes

on him. As I looked at him, I was thrilled with a most beautiful inspiration. I

could regenerate myself by doing an act of lovely charity.

“Wait a minute, boy.”

Disregarding the stale bread, I cut a big generous slice of fresh, sweet smelling

bread that Sung Sung, our one very old Chinese servant, had made that day. Heaping

it thick with brown sugar, I handed it to the boy.

“There, beggar boy,” I said generously, “you can eat it all.”

He took it with both hands, greedily, and now as I looked at him another fiendish

impulse seized me. Big boys had often hit me, and although I fought back as

valiantly and savagely as my puny fists would let me, I had always been worsted,

and had been made to realize the weakness of my sex and age. Now as I looked at

that beggar boy, I realized that here was my chance to hit a big boy. He was

smiling at me gratefully across that slice of sugared bread, and I leaned over and

suddenly pinched him hard on each of his cheeks. His eyes bulged with amazement,

and I still remember his expression of surprise and pained fear. I made a horrible

grimace at him and then ran out of the room.

There was a long, black period when we knew acutely the meaning of what papa

wearily termed “Hard Times.” Even in “Good Times” there are few people

who buy paintings, and no one wants them in “Hard Times.” A terrible epidemic

of smallpox broke out in the city. The French and not the English Canadians were

the ones chiefly afflicted, and my father set this down to the fact that the

French resisted vaccination. In fact, there were anti-vaccination riots all over

the French quarter, where we lived.

And now my father, in this desperate crisis, proved the truth of the old adage

that “Blood will tell.” Ours was the only house on our block, or for that

matter the surrounding streets, where the hideous yellow sign “PICOTTE” (small pox) was not conspicuously nailed

upon the front door, and this despite the fact that we were a large family of

children. Papa hung sheets all over the house, completely saturated with

disinfectants. Every one of us children were vaccinated, and were not allowed to

leave the premises. Papa himself went upon all the messages, even doing the

marketing.

He was not absentminded in those days, nor in the gruelling days of dire poverty

that followed the plague. Child as I was, I vividly recall the terrors of that

period, going to bed hungry, my mother crying in the night and my father walking

up and down, up and down. Sometimes it seemed to me as if papa walked up and down

all night long.

My brother Charles, who had been for some time our main support, had married (the

girl we did not like), and although he fervently promised to continue to

contribute to the family’s support, his wife took precious care that the

contribution should be of the smallest, and she kept my brother, as much as she

could, from coming to see us.

A day came when, with my mother and it seemed all of my brothers and sisters, I

stood on a wharf waving to papa on a great ship. There he stood, by the railing,

looking so young and good. Papa was going to England to try to induce

grandpapa—that grandfather we had never seen—to help us. We clung about mama’s

skirts—poor little mama, who was half distraught—and we all kept waving to papa,

with our hats and hands and handkerchiefs, and calling out:

“Good-by, papa! Come back! Come back soon!” until the boat was only a dim,

shadowy outline.

The dreadful thought came to me that perhaps we would never see papa again!

Suppose his people, who were rich and grand, should induce our father never to

return to us !

I had kept back my tears. Mama had told us that none of us must let papa see us

cry, as it might “unman” him, and she herself had heroically set the example

of restraining her grief until after his departure. Now, however, the strain was

loosened. I fancied I read in my brothers’ and sisters’ faces—we were all

imaginative and sensitive and excitable—my own fears. Simultaneously we all began

to cry.

Never will I forget that return home, all of us children crying and sobbing, and

mama now weeping as unconcealedly as any of us, and the French people stopping us

on the way to console or commiserate with us; but although they repeated over and

over, “Pauvres petits enfants! Pauvre petite mère!” I saw their significant

glances, and I knew that in their minds was the same treacherous thought of my

father.

But papa did return! He could have stayed in England, and, as my sister Ada

extravagantly put it, “lived in the lap of luxury,” but he came back to his

noisy, ragged little “heathens,” and the “painting, painting of pot-boilers

to feed my hungry children.”

“Monsieur de St. Vidal is ringing the

door-bell,” called Ellen. “Why don’t you open the door, Marion. I believe

he has a birthday present for you in his hand.”

It was my sixteenth birthday, and Monsieur de St.

Vidal was my first beau! He was a relative of our neighbors, the Prefontaines, and

I liked him pretty well. I think I chiefly liked to be taken about in his stylish

little dog-cart. I felt sure all the other girls envied me.

“You go, Ellen, while I change my dress.”

I was anxious to appear at my best before St. Vidal. It was very exciting, this

having a beau. I would have enjoyed it much more, however, but for the interfering

inquisitiveness of my sisters, Ada and Ellen, who never failed to ask me each time

I had been out with him, whether he had “proposed” yet or not.

Ellen was running up the stairs, and now she burst into our room excitedly, with a

package in her hand.

“Look, Marion! Here’s your present. He wouldn’t stop—just left it, and he said,

with a Frenchy bow—Whew! I don’t like the French!—‘Pour

Mamselle Marion, avec mes compliments!’” and Ellen mimicked St.

Vidal’s best French manner and voice.

I opened the package. Oh, such a lovely box of paints—a perfect treasure!

“Just exactly what I wanted!” I cried excitedly, looking at the little tubes,

all shiny and clean, and the new brushes and palette.

Ada was sitting reading by the window, and now she looked up and said:

“Oh, did that French wine merchant give that to Marion?”

She cast a disparaging glance at the box, and then, addressing Ellen, she

continued:

“Marion is disgustingly old for sixteen, but, of course, if he gives her

presents—” (he had never given me anything but candy before)

“he will propose to her, I suppose. Mama married at sixteen, and I suppose

some people—” Ada gave me another look that was anything but

approving—“are in a hurry to get married. I

shall never marry till I am twenty-five!” Ada was twenty.

This time, Ellen, who was eighteen, got the condemning look. Ellen was engaged to

be married to an American editor, who wrote to her every day in the week and

sometimes telegraphed. They were awfully in love with each other. Ellen said

now:

“Oh, he’ll propose all right. Wallace came around a whole lot, you know, before

he actually popped.”

“Well, maybe so,” said Ada, “but I think we ought to know that French wine

merchant’s intention pretty soon. I’ll ask him if you like,” she

volunteered.

“No, no, don’t you dare!” I protested.

257

“Well,” said Ada, “if he doesn’t propose to you soon, you ought to stop

going out with him. It’s bad form.”

That evening St. Vidal called and took me to the rink, and I enjoyed myself

hugely. He was a graceful skater, and so was I, and I felt sure that everyone’s

eye was upon me. I was very proud of my “beau,” and I secretly wished that he

was blond. I did prefer the English type. However, conscious of what was expected

of me by my sisters, I smiled my sweetest on St. Vidal, and by the time we started

for home I realized, with a thrill of anticipation, that he was in an especially

tender mood. He helped me along the street carefully and gallantly.

It was a clear, frosty night, and the snow was piled up as high as our heads on

each side of the sidewalks. Suddenly St. Vidal stopped, and drawing my hand

through his arm, he began, with his walking stick, to write upon the snow:

“Madame Marion de St. Vida—”

Before he got to the “l” I was seized with panic. I jerked my hand from his

arm, took to my heels and ran all the way home.

Now it had come—that proposal, and I did not want it. It filled me with

embarrassment and fright. When I got home, I burst into Ada’s room and gasped:

“It’s done! He did propose! B-but I said—I said—” I hadn’t said anything at

all.

“Well?” demanded Ada.

“Why, I’m not going to, that’s all,” I said.

Ada returned to the plaiting of her hair. Then she said skeptically:

“H’m, that’s very queer. Are you sure he proposed, because

I heard he was all the time engaged to a girl in Côte des

Neiges.”

“Oh, Ada,” I cried, “do you suppose he’s a bigamist? I think I’m fortunate

to have escaped from his snare!”

The next day Madame Prefontaine told mama that

St. Vidal had said he couldn’t imagine what in the world I had run away suddenly

from him like that for, and he said:

“Maybe she had a stomach-ache.”

“Ellen, don’t you wish something would happen?”

Ellen and I were walking up and down the street near the English church.

“Life is so very dull and monotonous,” I went on. “My! I would be glad if

something real bad happened—some sort of tragedy. Even that is better than this

deadness.”

Ellen looked at me, and seemed to hesitate.

“Yes, it’s awful to be so poor as we are,” she answered, “but what I would

like is not so much money as fame, and, of course, love. That usually goes with

fame.”

Ellen’s fiancé was going to be famous some day. He was in New York, and had

written a wonderful play. As soon as it was accepted, he and Ellen were to be

married.

“Well, I tell you what I’d like above everything else on earth,” I said

sweepingly. “I would love to be a great actress, and break everybody’s hearts.

It must be perfectly thrilling to be notorious, and we certainly are miserable

girls.”

We were chewing away with great relish the contents of a bag of candy.

“Anyhow,” said Ellen, “you seem to be enjoying that candy,” and we both

giggled.

Two men were coming out of the side door of the church. Attracted by our laughter,

they came over directly to us. One of them we knew well. He was Jimmy McAlpin, the

son of a fine old, very rich, Scotch lady, who had always taken an interest in our

family, and especially mama. Jimmy, though he took up the collection in church,

had been, so heard the neighbors whisper to mama, once very dissipated. He had

known us since we were little girls, and always teased us a lot. He would come up

behind me on the street and pull my long plait of hair, saying: “Pull the

string, gentlemen and ladies, and the figure moves!”

Now he came smilingly up to us, followed by his friend, a big stout man, with a

military carriage and gray moustache. I recognized him, too, though we did not

know him. He was a very rich and important citizen of our Montreal. Of him also I

had heard bad things. People said he was “fast.” That was a word they always

whispered in Montreal, and shook their heads over, but whenever I heard it, its

very mystery and badness thrilled me somehow. Ada said there was a depraved and

low streak in me, and I guiltily admitted to myself that she was right.

“What are you girls laughing about?” asked Jimmy, a question that merely

brought forth a fresh accession of giggles.

Colonel Stevens was staring at me, and he had thrust his right eye into a shining

monocle. I thought him very grand and distinguished looking, much superior to St.

Vidal. Anyway we were tired of the French, having them on all sides of us, and as

I have said, I admired the blond type of men. Colonel Stevens was not exactly

blond, for his hair was gray (he was bald on top, though his hat covered that),

but he was typically British, and somehow the Englishmen always appeared to me

much superior to our little French Canucks, as we called them.

Said the colonel, pulling at his moustache: “A laughing young girl in a

pink-cotton frock is the sweetest thing on earth.”

I had on a pink-cotton frock, and I was laughing. I thought of what I had heard

Madame Prefontaine say to mama—in a whisper: “He is one dangerous man—dat

Colonel Stevens, and any woman seen wiz him will lose her reputation.”

“Will I lose mind?” I asked myself. I must say my heart beat, fascinated,

with the idea. Something, now, was really happening, and I was excited and

delighted.

“Can’t we take the ladies”—I nudged Ellen—“some place for a little

refreshment,” said the colonel.

“No,” said Ellen, “mama expects us home.”

“Too bad,” murmured the colonel, very much disappointed, “but how about

some other night? To-morrow, shall we say?”

Looking at me, he added: “May I send you some roses, just the color of your

cheeks?”

I nodded from behind Ellen’s back.

“Come on,” said Ellen brusquely, “we’d better be getting home. You know

you’ve got the dishes to do, Marion.”

She drew me along. I couldn’t resist looking back, and there was that fascinating

colonel, standing stock still in the street, still pulling

304 at his

moustache, and staring after me. He smiled all over, when I turned, and blew me an

odd little kiss, like a kind of salute, only from his lips.

That night, when Ellen and I were getting ready for bed, I said: “Isn’t the

colonel thrillingly handsome, though?”

“Ugh! I should say not,” said Ellen. “Besides, he’s a married man, and a

flirt.”

“Well, I guess he doesn’t love his old wife,” said I.

“If she is old,” said Ellen, “so is he—maybe older. Disgusting!”

All next day I waited for that box of roses and late in the afternoon, sure

enough, it came, and with it a note:

Dear Miss Marion:

Will you and your charming sister take a little drive with me and a

friend this evening? If so, meet us at eight o’clock, corner of St. James

and St. Denis streets. My friend has seen your sister in Judge Laflamme’s

office (Ellen worked there) and he is

very anxious to know her. As for me, I am thinking only of when I shall

see my lovely rose again. I am counting the hours!

Devotedly,

Fred Stevens.

The letter was written on the stationary of the fashionable St. James Club. Now I

was positive that Colonel Stevens had fallen in love with me. I thought of his

suffering because he could not marry me. In many of the French novels I had read

men ran away from their wives, and I thought: “Maybe the colonel will want me to

elope with him, and if I won’t, perhaps he will kill himself,” and I began

to feel very sorry to think of such a fine-looking soldierly man as Colonel

Stevens killing himself just because of me.

When I showed Ellen the letter, after she got home from work, to my surprise and

delight, she said:

“All right, let’s go. A little ride will refresh us, and I’ve had a hard week of

it, but better not let mama know where we’re going. We’ll slip out after

supper, when she’s getting the babies to sleep.”

Reaching the corner of St. James and St. Denis streets that evening, we saw a

beautiful closed carriage, with a coat of arms on the door, and a coachman in

livery jumped down and opened the door for us. We stepped in. With the colonel was

a middle-aged man, with a dry yellowish face and a very black—it looked

dyed—moustache.

“Mr. Mercier!” said the colonel, introducing us.

“Oh,” exclaimed Ellen, “are you related to the Premier?”

“Non, non, non,” laughed Mr. Mercier, and turning about in the seat, he began

to look at Ellen, and to smile at her, until the ends of his waxed moustache

seemed to jump up and scratch his nose. Colonel Stevens had put his arm just at

the back of me, and as it slipped down from the carriage seat to my waist, I sat

forward on the edge of the seat. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings by telling him

to take his arm down, and still I didn’t want him to put it around me. Suddenly

Ellen said:

“Marion, let’s get out of this carriage. That beast there put his arm around me,

and he pinched me, too.” She indicated Mercier. She was standing up in the

carriage, clutching at the strap, and she began to tap upon the window, to attract

the attention of the coachman. Mr. Mercier was cursing softly in French.

“Petite folie!” he said, “I am not meaning

to hurt you—joost a little loving. Dat is all.”

“You ugly old man,” said Ellen, “do you think I want you to

love me? Let me get out!”

“Oh, now, Miss Ellen,” said the colonel, “that is too rude. Mr. Mercier is

a gentleman. See how sweet and loving your little sister is.”

“No, no!” I cried, “I am not sweet and loving. He had no business to touch

my sister.”

Mr. Mercier turned to the colonel.

“For these children did you ask me to waste my time?” and putting his head

out of the carriage, he simply roared:

“Rue Saint Denis! Sacré!”

They set us down at the corner of our street. When we got in a friend of papa’s

was singing to mama and Ada in the parlor:

“In the gloaming, oh, my darling, When the lights are dim and low.”

He was one of many Englishmen, younger sons of aristocrats, who, not much good in

England, were often sent to Canada. They liked to hang around papa, whose family

most of them knew. This young man was a thin, harmless sort of fellow, soft spoken

and rather silly, Ellen and I thought, but he could play and sing in a pretty,

sentimental way, and mama and Ada would listen by the hour to him. He liked Ada,

but Ada pretended she had only an indifferent interest in him. His father was the

Earl of Albemarle, and Ellen and I used to make Ada furious by calling her

“Countess,” and bowing mockingly before her.

Walking on tiptoe, Ellen and I slipped by the parlor door, and up to our own room.

That night, after we were in bed, I said to Ellen:

“You know, I think Colonel Stevens is in love with me. Maybe he will want me to

elope with him. Would you, if you were me?”

“Don’t be silly; go to sleep,” was Ellen’s cross response. She regretted very

much taking that ride, and she said she only did it because she got so tired at

the office all day, and thought a little ride would be nice. She had no idea, she

said, that those “two old fools” would act like that.

Wallace, Ellen’s sweetheart, had not sold his play, but he expected to any day. He

was, however, impatient to be married—they had now been engaged over a year and he

wrote Ellen that he could not wait, anyway, more than two or three months longer.

Meanwhile Ellen secured a much better position.

The new position was at a greater distance from our house, and as she had to be at

the office early she decided to take a room down-town. Papa at first did not want

her to leave home, but Ellen pointed out that Hochelaga was too far away from her

office, and then she added, to my delight, that she’d take me along with her. I

could make her trousseau and cook for us both, and it wouldn’t cost any more for

two than for one.

Mama thought we were old enough to take care of ourselves, “for,” said she,

“when I was Ellen’s age I was married and had two children. Besides,” she

added, “we are crowded for room in the house, and it will only be for a month or

two.”

So Ellen secured a little room down-town. I thought the house was very grand, for

there was thick carpet on all the floors and plush furniture in the parlor.

We had been at Mrs. Cohen’s (that was the name of our landlady) less than a month,

when Wallace wrote he could wait no longer.

He had not sold his play but he had a very good position now as associate editor

of a big magazine, and he said he was making ample money to support a wife. So he

was coming for his little Ellen at once. We were terribly excited, particularly as

Wallace followed up the letter with a telegram to expect him next day, and sure

enough the next day he arrived.

He did not want any “fussy” wedding. Only papa and I were to be present.

Wallace did not even want us, but Ellen insisted. She looked sweet in her little

dress (I had made it), and although I knew Wallace was good, and a genius, and

adored my sister, I felt broken-hearted at the thought of losing her, and it was

all I could do to keep from crying at the ceremony.

As the train pulled out I felt so utterly desolate, that I stretched out my arms

to it and cried out aloud:

“Ellen, Ellen, please don’t go! Take me, too!” I never realized till then how

much I loved my sister. Dear little Ellen, with her love of all that was best in

life, her sense of humor, her large, generous heart, and her absolute purity. If

only she had stayed by my side I am sure her influence would have kept me from all

the mistakes and troubles that followed in my life, if only by her disgust and

contempt of all that was dishonorable and unclean. But Wallace had taken our

Ellen, and I had lost my best friend, my sister and my chum.

I was at the age—nearly eighteen now—when girls want and need chums and

confidantes. I was bubbling over with impulses that needed and outlet, and only

foolish young things like myself were capable of understanding me. With Ellen

gone, I sought and found girl friends I believed to be congenial.

My sister Ada, because of her superiority in age and character to me, would not

condescend to chum with me. Nevertheless, she heartily disapproved of my choice in

friends, and constantly reiterated that my tastes were

305 low. Life was

a serious matter to Ada, who had enormous ambitions, and had already been promised

a position on our chief newspaper, to which she had contributed poems and stories.

To Ada, I was a frivolous, silly young thing, who needed constantly to be

squelched, and she undertook to do the squelching, unsparingly, herself.

“Since we are obliged,” said Ada, “to live in a neighborhood with people

who are not our equals, I think it a good plan to keep to ourselves. That’s the

only way to be exclusive. Now that Gertie Martin” (Gertie was my latest

friend) “is a noisy American girl. She talks through her nose, and is always

criticizing the Canadians and comparing them with the Yankees. As for that Lu

Fraser” (another of my friends) “she can’t even speak the Queen’s English

properly, and her uncle keeps a saloon.”

Though I stoutly defended my friends, Ada’s nagging had an unconscious effect upon

me, and for a time I saw very little of the girls.

Then one evening Gertie met me on the street, and told me that, through her

influence, Mr. Davis (also an American) had decided to ask me to take a part in

“Ten Nights in a Barroom,” which was to be given at a “Pop” by the

Montreal Amateur Theatrical Club, of which he was the head. I was so excited and

happy about this that I seized hold of Gertie and danced with her on the sidewalk,

much to the disgust of my brother, Charles, who was passing with his new wife.

Mr. Davis taught elocution and dramatic art, and he was a man of tremendous

importance in my eyes. He was always getting up concerts and entertainments, and

no amateur affair in Montreal seemed right without his efficient aid. The series

of “Pops” he was now giving were patronized by all the best people of the

city and he had an imposing list of patrons and patronesses. Moreover the plays

were to be produced in a real theater, not merely a hall, and so they had somewhat

the character of professional performances.

To my supreme joy, I was given the part of the drunkard’s wife, and there were two

glorious weeks in which we rehearsed and Mr. Davis trained us. He said one day

that I was the “best actress” of them all, and he added that although he

charged $25 a month to his regular pupils he would teach me for ten, and if I

couldn’t afford that, for five; and if there was no five to be had, then for

nothing. I declared fervently that I would repay him some day, and he laughed, and

said: “I’ll remind you when that ‘some day’ comes.”

Well, the night arrived, and I was simply delirious with joy. I learned how to

“make up,” and I actually experienced stage fright when I first went on,

but I soon forgot myself.

When I was crawling on the floor across the stage, trying to get something to my

drunken husband, a voice from the audience called out:

“Oh, Ma-ri-on! Oh, Ma-ri-on! You’re on the bum! You’re on the bum!”

It was my little brother, Randle, who with several small boys had got free seats

away up front by telling the ticket man that his sister was playing the star part.

I vowed mentally to box his ears good and hard when I got home.

When the show was over Mr. Davis came to the dressing-room and said, before all

the girls:

“Marion, come to my studio next week and we’ll start those lessons, and when we

put on the next ‘Pop,’ which I believe will be ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ we will

find a good part for you.”

“Oh, Mr. Davis,” I cried, “are you going to make an actress of me?”

“We’ll see! We’ll see!” he said, smiling. “It will depend on yourself, and

if you are willing to study.”

“I’ll sit up all night long and study,” I assured him.

“The worst thing you could do,” he answered. “We want to save these

peaches,” and he pinched my cheek.

Mr. Davis did lots of things that in other men would have been offensive. He

always treated us girls as if we were children. People in Montreal thought him

“sissified,” but I am glad there are some men more like the gentler

sex.

So I began to take lessons in elocution and dramatic art. Oh! but I was a happy

girl in those days. It is true, Mr. Davis was very strict, and he would make me go

over lines again and again before he was satisfied, but when I got them finally

right and to suit him, he would rub his hands, blow his nose and say:

“Fine! Fine! Marion, there’s the real stuff in you.”

He once said that I was the only pupil he had who had an atom of promise in her.

He declared Montreal peculiarly lacking in talent of that sort, though he said he

had searched all over the place for even a “spark of fire.” I, at least,

loved the work, was deadly in earnest, and, finally, so he said, I was pretty, and

that was something.

We studied “Camille,” “The Marble Heart,” and “Romeo and Juliet.”

All of my spare time at home I spent memorizing and rehearsing. I would get a

younger sister, Nora, who was absorbedly interested, to act as a dummy. I would

make her be Armand or Armand’s father.

“Now, Nora,” I would say, “when I come to the word ‘Her,’ you must say:

‘Camille! Camille!’”

Then I would begin, addressing Nora as Armand:

“You are not talking to a cherished daughter of society, but a woman of the

world, friendless and fearless. Loved by those whose vanity she gratifies,

despised by those who ought to pity her—her—Her—”

I would look at Nora and repeat: “Her—!” and Nora would wake up from her

trance of admiration of me and say:

“Camel! Camel!”

“No, no!” I would yell. “That is—” (pointing to the

right—Mr. Davis called that “dramatic action”) “your way!

This way—” (pointing to the left) “is mine!”

Then throwing myself on the dining-room sofa, I would sob and moan and cough

(Camille had consumption, you may recall), and what with Nora crying with sympathy

and excitement, and the baby generally waking up there would be an awful noise in

our house.

I remember papa coming half way down the stairs one day and calling out:

“What the dickens is the matter with that Marion? Has she taken leave of her

sense?”

Mama answered from the kitchen:

“No, papa, she’s learning elocution and dramatic art from Mr. Davis; but I’m

sure she’s not suited to be an actress, for she lisps and her nose is too

short. But do make her stop, or the neighbors will think we are

quarreling.”

“Stop this minute!” ordered papa, “and don’t let me hear any more such

nonsense.”

I betook myself to the barn.

The snow was crisp and the air as cold as ice. We were playing the last

performance of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” We had been playing it for two weeks, and

I had been given two different parts—Marie St. Claire, in which, to my joy, I wore

a gold wig and lace tea-gown—which I made from an old pair of lace curtains and a

lavender silk dress mama had had when they were rich and she dressed for

dinner—and Cassy. I did love that part where Cassy says:

“Simon Legree, you are afraid of me, and you have reason to be, for I have got

the devil in me!”

I used to hurl those words at him, and glare until the audience clapped me for

that. Ada saw me play Cassy one night, and she went home and told mama that I had

“sworn like a common woman before all the people on the stage” and that I

ought not to be allowed to disgrace the family. But little I cared for Ada in

those days. I was learning to be an actress!

On this last night, in fact, I experienced all the sensations of a successful

star. Someone had passed up to me, over the footlights, if you please, a real

bouquet of flowers, and with these clasped to my breast I had retired smiling and

bowing from the stage.

To add to my bliss, Patty Chase, the girl who played Topsy, came running in to say

that a gentleman friend of hers was “crazy” to meet me. He was the one who

had sent me the flowers. He wanted to know if I would not take supper with him and

a friend and Patty that night.

My! I felt like a regular professional actress. To think an unknown man had

admired me from the front, and was actually seeking my acquaintance! I hesitated,

however, because Patty was not the sort of girl I was accustomed to go out with. I

liked Patty pretty well myself, but my brother, Charles, had one day come to the

house especially to tell papa some things about her—he had seen me walking with

Patty on the street—and papa had forbidden me to go out with her again. As I

hesitated, she said:

“It isn’t as if they are strangers, you know. One of them, Harry Bond, is my own

fellow. You know how his folks are, and but for them we’d have been married

long ago. Well, Harry’s friend, the one who wants to meet you, is a swell, too,

and he hasn’t been out from England long. Harry says his folks are big nobs

over there, and he is studying law here. His folks send him a remittance and I

guess it’s a pretty big one, for he’s 306 living at the Windsor, and

I guess he can treat us fine. So come along. You’ll not get such a chance

again.”

“Patty,” I said, “I’m afraid I dare not. Mama hates me to be out late, and,

see, it’s eleven already.”

“Why, the night’s just beginning,” cried Patty.

There was a rap at the door, and Patty exclaimed:

“Here they are now!”

All the girls in the room were watching me—enviously, I thought—and one of them

made a catty remark about Patty, who had gone out in the hall, and was whispering

to the man. I decided not to go, but when I came out of the room there they were

all waiting for me, and Patty exclaimed:

“Here she is,” and, dragging me along by the hand, she introduced me to the

men.

I found myself looking up into the face of a tall man of about twenty-three. He

had light curly hair and blue eyes. His features were fine and clear cut, and, to

my girlish eyes, he appeared extraordinarily handsome and distinguished, far more

so even than Colonel Stevens, who had, up till then, been my ideal of manly

perfection. Everything he wore had an elegance about it, from his evening suit and

the rich fur-lined overcoat to his opera hat and gold-topped cane. I felt

flattered and overwhelmingly impressed to think that such a fine personage should

have singled me out for especial attention. What is more, he was looking at me

with frank and undisguised admiration. Instead of letting go my hand, which he had

taken when Patty introduced us, he held it while he asked me if he couldn’t have

the pleasure of taking me out to supper. As I hesitated, blushing and awfully

thrilled by the hand pressing mine, Patty said:

“She’s scared. Her mother won’t let her stay out late at night. She’s never been

out to supper before.”

Then she and Harry Bond burst out laughing, as if that were a good joke on me, but

Mr. Bertie (his name was the Honorable Reginald Bertie—pronounced Bartie) did not

laugh. On the contrary, he looked very sympathetic, and pressed my hand the

closer. I thought to myself:

“My! I must have looked lovely as Marie St. Claire. Wait till he sees me as

Camille.”

“I’m not afraid,” I contradicted Patty, “but mamma sits up for me.”

This was not strictly true, but it sounded better than to say that Ada always sat

up for anyone in the house who went out at night. She even used to sit up for my

brother Charles, before he was married, and I could just imagine the

cross-questioning she would put me through when I got in late. Irritated as I used

to be in those days at what I called Ada’s interference in my affairs, I know now

that she always had my best good at heart. Poor little delicate Ada! with her

passionate devotion and loyalty to the family, and her fierce antagonistic

attitude to all outside intrusion. She was morbidly sensitive.

Mr. Bertie quieted my fears by despatching a messenger boy to our house with a

note saying that I had gone with a party of friends to see the Ice Palace.

Even with Ada in the back of my mind I was now, as Patty would say, “in for a

good time,” and when Mr. Bertie carefully tucked the fur robes of the sleigh

about me I felt warm, excited and recklessly happy.

We drove over to the Square, where the Ice Palace was erected. The Windsor Hotel

was filled with American guests, who were on the balconies, watching the

torchlight procession marching around the mountain. My brother, Charles, was one

of the snowshoers, and the men were all dressed in white and striped blanket

overcoats, with pointed capuchons on their backs and heads and moccasins on their

feet. It was a beautiful sight, that procession, and looked like a snake of light

winding about old Mount Royal, and when the fireworks burst all about the

monumental Ice Palace, inside of which people were dancing and singing, really it

seemed to me like a scene in fairyland. I felt a sense of pride in our Montreal

and looking up at Mr. Bertie to note the effect of so much beauty upon him, I

found him watching me instead.

The English, when they first come out ot Canada, always assume an air of patronage

toward the “Colonials” as they call us, just as if, while interested, they

are also highly amused by our crudeness. Now Mr. Bertie said:

“We’ve seen enough of this Ice Palace’s hard, cold beauty. Suppose we go

somewhere and get something warm inside us. Gad! I’m dry.”

Harry told the driver to take us to a place whose name I could not catch, and

presently we drew up before a brilliantly lighted restaurant. Harry Bond jumped

out, and Patty after him. I was about to follow, when I felt a detaining hand upon

my arm, and Bertie called out to Bond:

“I’ve changed my mind, Bond. I’ll be hanged if I care to take Miss Ascough into

that place.”

Bond was angry, and demanded to know why Bertie had told him to order dinner for

four. He said he had called the place up from the theatre.

“Never mind,” said Bertie, “I’ll fix it up with you later. Go on in without

us. It’s all right.”

(Be sure to follow up these experiences of

“Marion” in the May issue of Hearst’s)