Chapter XIX – Continued

The Prince found his voice.

“Then by the royal blood of my ancestors, I swear,” he cried, “that I shall be guilty of the same offense as thy honorable parent, and for thy sweet sake, I, too, shall become an Eta.”

With a little, trembling cry she started towards him.

“But thy cause! Oh, my lord, thy noble cause!”

“The cause!” He threw back his head and laughed with buoyant joyousness.

“Fuji-wara,” he said, “do you not perceive that a new life is about dawn for this Japan of ours?”

“A new life,” she repeated, breathlessly, hanging upon the words that escaped his lips.

“A new life,” he said, “with our country no longer broken up into factions, when men shall have equal rights and privileges.”

He smiled at her rapt face, and possessed himself of both her little hands.

“Dearest and sweetest of maidens,” he said, tenderly, “in marrying me you do not wed a prince. I am pledged to the welfare of the people. Know you not that the great cause of the Imperialist will bring about that Restoration which will overturn all these crushing tyrannies and injustices which press our people to the earth? Repeat with me, then: ‘Daigi Meibunor! Banzai the Imperialist!’”

Suddenly she remembered the blow she had dealt the cause. Her head fell upon their clasped hands.

But over her fallen head the voice of the Prince Keiki was full of joy.

“And now have I not heard the great trouble, and burst it like a bubble? Henceforward, then, let there be only happiness and joy in these eyes and these liips.” Reverently he pressed her eyes and lips.

Genji was heard outside the door. His face was very grave and his whole appearance perturbed when he entered.

Bowing deeply to the Prince, he addressed him hastily:

“Your excellency, the Lord of Catzu, has arrived at my insignificant house and is below. It is his wish that the marriage of his niece should be celebrated without further delay. I come to you, therefore, to beg that you will consent to its immediate consummation.”

“I comply with gladness,” replied the Prince, “but may I inquire the reason for this haste?”

“The Lord Catzu Toro is in critical peril in your august father’s province.”

“Enough!” interrupted the Prince, impulsively. “You desire my immediate mediation in his behalf?”

He turned to Wistaria with an exclamation of delight. “Now,” said he, “we shall see all our troubles melt into thin air like mist before the sun.”

“But I have not told you all—there is more still to tell. I pray you—” Wistaria began.

“There is no time,” interrupted Genji, severely, “and I beg your highness will convince the Lady Wistaria of the necessity for haste.”

“That is right,” said the Prince. “There is a whole lifetime before us yet in which thou canst tell me thy heart. Come. Let us descend to the wedding-chamber.”

Chapter XX

No Prince of Japan had ever been wedded in so strange and lowly a fashion. There was not a sign or sound of the gratulation, rejoicing, or pomp which usually attend such ceremonies. When the Prince Keiki and the Lady Wistaria, attended by the samurai Genji, entered the homely wedding apartment, they found a small group, pale and solemn, awaiting them. It consisted of the Lord and Lady Catzu and one who was a stranger to Keiki, but whom he knew to be the father of the Lady Wistaria.

The waiting party bowed very low and solemnly to those who had just entered. Their greeting was returned with an equal gravity and grace. There was a pause—a hush. Keiki looked about him inquiringly, and then he shivered. The true solemnity of the occasion dawned upon him so that even the near joy of possessing Wistaria at last passed from his mind. He was about to join through marriage two families who hitherto had had for each other nothing save hatred and detestation.

Timid and pale as his glance was, he scarcely dared to look at the Lady Wistaria, though he knew she was so weak and faint that the samurai Genji had to support her.

Somewhat sharply, the voice of the Lady Evening Glory broke the silence.

“Why do we wait?”

The Lord Catzu stirred uneasily, glancing from the bridal couple to his wife, and then to the inscrutable face of Shimadzu.

“If I may be permitted to remark,” he said, apologetically, “the Lady Wistaria is certainly garbed unbefitting her rank and race.”

“Chut!” said his wife, angrily, “you would delay matters for such a trifle? Every moment counts now against our son. Will you let such an insignificant matter as the dress of your unworthy niece hasten the possible death of our beloved?”

“When it is her wedding-dress, yes,” said Catzu, stubbornly. “May I be stricken blind before I witness such a disgrace brought upon my honorable niece’s dignity. She must be married as befits her rank, I repeat.”

A sour smile played over the features of the Lady Evening Glory.

“That is true. Well, her rank is that of the Eta,” she said, tartly.

Having found the courage to disagree with his lady, Catzu now set her at complete defiance. He marched towards the door.

“Very well, then. I refuse to witness such an outrageous ceremony. The lady may have Eta kindred, but do not forget that she has also the blood of royalty in her veins.”

His consort could hardly suppress her fury.

“I appeal to you, honored brother,” she said. “How shall it be?”

“And I,” exploded Catzu, who was in an evil and contrary temper, “appeal to you, my Lord of Mori,” and he bowed profoundly to the Prince.

Shimadzu made no response. His glance met that of the troubled Prince. Keiki flushed under his penetrating eyes. Then he spoke with graceful dignity, bowing meanwhile to the trembling Wistaria.

“Let her be garbed,” he said, “as befits the daughter of her father and the bride of a Prince of Mori.”

There was silence for a space. Then Shimadzu made an imperative gesture to Genji, who gently led the girl from the chamber, followed by the angrily resigned Lady Evening Glory.

The three men, now alone, waited in strained silence for Wistaria’s return. Straight and stiff, with heads somewhat bent to the floor, they remained standing in almost identical attitudes. Gradually, however, Catzu broke the tension by an attempt to relieve his excessive nervousness. Resting first on one foot and then on the other, he shifted about. His eyes lingered in painful sympathy upon the Prince, and then irresolutely turned to the samurai. Perspiration stood out on the lord’s brow. He was suffering physically from the strain.

After a long interval of this intolerable silence, the doors of the chamber were again pushed aside. The samurai Genji entered. Bowing deeply, he announced:

“The Lady Wistaria and her august aunt enter the honorable chamber!”

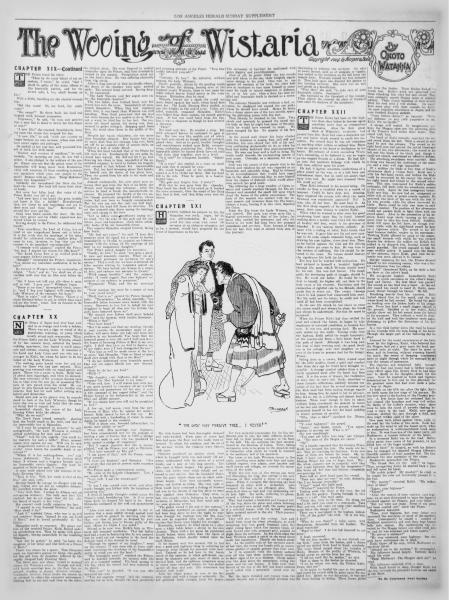

The two ladies, close behind Genji, now followed him into the room. Immediately all prostrated themselves. When they had regained their feet, it was found that Wistaria was still kneeling. Then Genji perceived that she had not risen because she was unable to do so. Without a word, he lifted her to her feet. One moment she leaned against his strong arm, then seemed to gather strength. Stepping apart from him, she stood alone there in the middle of the floor.

Despite her waxen whiteness, she was more than beautiful—ethereal. Her lacquer hair was no more dark than her strange, long eyes, both set off by an exquisite robe of ancient style, as befitted a lady of noble blood.

When her hand touched that of the Prince he felt cold as ice. Involuntarily his own palm inclosed hers warmly. He did not let it go, but drawing her closer to him, unmindful of the assembled company, he tried to fathom the tragedy that seemed to lurk behind her impenetrable eyes. But, her head drooping above their hands, he behold only the sheen of her glossy hair. Then she passed from his side to her uncle and father.

Almost mechanically, his eyes never once relaxing their gaze from the face of his bride, the Prince went through the ceremony. After the service he tried to break the uncomfortable restraint. He proposed the health of the two noble though previously misguided families, whose union had now been so happily consummated. But his own cup was the only one held high. Gradually his hand fell from its elevation. He set the untasted sake down among the marriage cups and sprang to his feet.

“Let us diffuse some merriment among us,” he cried, “for the sake of the gods and for our future peace and happiness. Such undue solemnity bodes ill for our honorable future.”

The samurai Shimadzu stepped forward, facing him fairly.

“My lord and prince,” he said, “I have this moment given the signal for a courier to hasten immediately to Choshui to acquaint my bitterest enemy with the tidings of the marriage of his heir to my insignificant daughter.”

The Prince smiled, despite his uneasiness.

“Surely, my lord,” he said, “you make a goodly new and honorable custom. What! an announcement, perchance an invitation for one’s enemy! That is well, for we have overturned all false maxims relating to vengeance against an enemy. We have buried our wrongs in a union of love, and embrace our enemies as friends.”

“With august humility,” said the samurai, coldly, “I would suggest that your highness’ assurance of our embrace is premature.”

“Premature! What, and this my marriage day!”

“Your marriage day may be a source of woe to your proud house.”

“Well, that is so,” agreed the Prince, thoughtfully. “Nevertheless,” he added, cheerfully, “my honorable father becomes more lenient with the years. Moreover he has but to behold his new daughter to forget all else save the fortune the gods have bestowed upon us.”

“Be assured your father shall never behold her,” said the samurai, with incisive fierceness.

“What is that?”

“You have heard.”

“Bud I do assure you that my marriage, though it may provoke the momentary anger of my father, will never debar my lady wife from her position in our household. You forget that my honored parent is very old, and I shall soon have the honor of becoming Prince of Mori in my own right. I shall then have no lord to deprive me of my rights, even if I had disregarded the law.”

“You may as well be made aware of the fact at once,” said Shimadzu, “that no blood of mine shall ever mingle with that of the Mori!”

“I do not understand your honorable speech. Has not our august bloods just now become united?”

“Only by the law, my lord.”

“Well--?”

“My daughter, your highness, shall never accompany her Mori husband to his home.”

“Very well, then. I will remain here with her. I am quite satisfied to renounce all my worldly ambitions and possessions for her sake, if such is the command of her august father,” and the Prince bowed to his father-in-law in the most filial and affable manner.

“If you remain here you will not be permitted to live.”

A low cry, half moan, came from the new Princess of Mori, who lay against her uncle’s breast. Keiki turned to look at her at that cry. He was seized with a foreboding of events to come. Again he turned to the samurai.

“Will it pleas you, honored father-in-law, to speak more plainly to me?”

“Very well. This marriage, your highness, has been consummated not for the purpose of uniting a pair of lovers, but to fulfill a pledge which was made to one who was murdered by your parent—a pledge of vengeance.”

“But I cannot perceive how this is accomplished,” said the Prince, now pale as Wistaria.

“You have married an Eta girl.”

“I am aware of that,” said the Prince, somewhat proudly.

“I have not finished,” said Shimadzu, “Are you aware that you are at present under sentence of death?”

The Prince made a contemptuous motion.

“By order of the

bakufu (shogunate). Yes, I am aware of the fact.”

“Very well. I am the executioner!”

“You!”

“It was I who caused your arrest, and afterwards brought you hither with the intention of executing you.”

A flood of horrible thoughts rushed across the Prince’s mind, bewildering him. As if to press them back, he clasped his hand to his head. Shimadzu continued in his cold and monotonous voice:

“After your arrest, it was brought to my attention that a more subtle revenge against your parent could be gained by marrying you into that very class of people so despised by your father, and forcing you to become guilty of the same offense for which I was exiled.”

Stirred as he now was, Keiki’s faith in Wistaria remained unshaken. That her father had had a hand in betraying him he was assured, but he could not yet recognize in the deed the delicate hand of the woman he loved.

“Through the agency of my daughter,” went on the samurai, “I was soon able to learn sufficient concerning the workings of the Imperialist party of which you are the head—”

“The Imperialist party!” repeated the Prince, and he bounded towards the samurai with the cry of a wounded animal. His hand sprang to his hip, where his sword had been restored to its sheath.

“You—you!” he shouted. “It was you who betrayed me—who—”

“You are augustly wrong,” said the samurai, moving not an inch, despite the close proximity and menacing attitude of the Prince. “You honorably betrayed yourself!”

“I!”

“Certainly. To her.” He indicated, without naming, the Lady Wistaria.

Slowly, painfully, driven by the goading words of the father, the blazing, burning eyes of the husband sought Wistaria, there to rest upon her while infinite horror found mirror in his countenance. Motionless thus he stood.

Wistaria, braced for a shock she could not meet, leaned against her uncle, whose head bent over her. The Lady Evening Glory smiled, as one who delights in the soul of a cat. Calm, satisfied, unmoved, remained Shimadzu. Keiki’s eyes bulged from their sockets, his mouth gaped open. At last one word burst from his lips, but it was as eloquent as though he had uttered a thousand.

“Thou!”

Her hand sank low. He recoiled a step. But with entranced horror he continued to gaze at her. Her face was like marble, out of which her dark eyes stared as though made of polished, glazed china. And as he gazed, terrible thoughts and remembrances rushed upon Keiki, overpowering, weakening, paralyzing him. After a long, immovable silence he leaned slowly forward until their faces, close together, were on a level.

“It is true?” he whispered, hoarsely. “Speak! Speak!”

“It is true,” she replied, in a voice so small and faint that it seemed so far away.

His sword leaped out of his scabbard. He raised it as if to strike her down. But his hand fell to his side. Then he spoke, in a hoarse, fearful voice:

“The gods may forgive thee. I never!”

With that he was gone from the chamber. They heard the clash of his sword as it touched the stone pavement, then the sound of his flying feet, loud at first, and then dying away into the silence.

Chapter XXI

Having fulfilled his purpose in life, the Shimadzu was ready, eager, for his own self-immolation. He had prepared for this event with strict observance of an elaborate etiquette, just as he, a samurai, would have prepared for any event of importance in his life.

The little house had been thoroughly cleansed and white-washed. Fresh mats of straw had been laid upon the floor, and the walls were recovered. To admit the sunshine, and the air of the out-door world, the windows were thrown wide apart.

Shimadzu produced an ancient chest, from which he brought forth rare and costly old garments, emblazoned with the crests of a proud family, and a pair of very long swords. The hilts were of black lacquer. The guard, ferule, cleats, and rivets, were richly inlaid and embossed in rare metals. But the beautiful blades were the parts which shone out in their noble, classic beauty. They were extremely narrow, glossy, and brittle as icicles. The very sight of them would have awakened a feeling of heroism and awe in the bosom of one less alive to what they signified than Shimadzu. They were, in fact, two swords which, belonging to a hundred ancestors of Shimadzu, had been used only in the most glorious service.

“The girded sword is the soul of the samurai,” and Shimadzu muttered an ancient saying. It had been long since he lost the right to wear them through his marriage into the Eta class, and now he regarded them with such intense emotion that fierce tears blinded his eyesight.

Reverently, tenderly, he lifted them to a place upon a white table before a shrine in his own chamber. Then with a low groan he prostrated himself before them, rather than the figure of the Daibutsu, which placidly rested upon the small throne.

In his inmost soul, this samurai felt he had done a good and righteous thing in achieving his vengeance, even though the innocent were sacrificed. Trained as he had been in the harsh school of the samurai, in which self-denial, contempt for pleasure and gain, scorn of death or physical hurt, and the righteous vengeance upon an enemy were esteemed virtues, he was steeled against all fear and pain. His conscience was satisfied with itself.

After his silent prayer, he rose to his feet very calmly and with a degree of solemnity. He had gathered fresh strength from his prayer. The ceremony of hari-kari he performed with grave dignity and punctiliousness.

First of all, he gently lifted the two swords and held them in the sun, their knightly significance strong in this mind. One was to use against all enemies of his lord, the other held ever in readiness to turn upon himself in atonement for fault or fainted suspicion of dishonor, or, as in his case, when a duty has been fulfilled and honorable death is desired as a crowning end.

The samurai Shimadzu was without a lord, or, rather, he disdained and cursed the one under whom he should have served. Hence he broke into a dozen pieces one of the two swords, spurning the glittering pieces with his foot.

Then silently he disrobed to the waist. Very slowly and precisely he pressed the sword into his body so that he might lose none of the pain, which he would have scorned to resist. No moan escaped his lips. No muscle of his face quivered.

As the sword sank deeper his brain whirled with the dizziness of nausea, but, still stiff and relentless, his arm obeyed the will of his soul, even continuing mechanically to do so when his head had fallen backward into semi-unconsciousness. He was one hour and a half in dying. No words could describe the excruciating nature of such pains. Certainly, as a samurai, his was a fitting end.

Such was the nature of this people that to his friends and relatives his act was regarded as an honorable and admirable thing. Had he faltered in its accomplishment they would have urged him to the deed, entreating him to save himself from the stigma of dishonor which would otherwise smirch his good name.

The following day a large number of Catzu samurai and vassals marched through the Eta settlement and ascended the small hill upon which stood the house of the public executioner. The body of the samurai was carried with the utmost respect and reverence from the Eta house, whence a train, bearing it in due state, departed for Catzu.

From the Eta house the Lady Wistaria, too, was carried. Her train was even more like a funeral procession than that of her father; for those who carried her norimono and who followed in its wake had long been her personal attendants and servitors. Now, because of their love for her, they wept at almost every step of the journey.

The two mournful processions left the Eta settlement side by side, but their different destinations led to their parting company at the base of the hill. The one carrying the dead samuraiturned in the direction of Catzu. There, fitting ceremonies were to be given to the departed soul of Shimadzu, after which he would be interred in the mortuary hall of his ancestors.

The train of the Lady Wistaria turned to the south, traveling many miles over bare and uninhabited regions, over plains, past hamlets and small towns and villages, on towards the mountains of the south.

While the last rays of the setting sun were still illumining the west, the cortege of the new Princess of Mori entered a forest of evergreen pines. When it emerged, the darkening sky had deepened its colors until a melancholy calm wrapped the land in an effulgent glow. The moon had risen on high and was shimmering out its holy light. The earth, reflecting its gleam, seemed a tableau of silent silver.

They had reached a beautiful and tranquil hill. At the top, above the pines and cedars inclosing it in nature’s own sacred wall, the amber peaks of a celestial temple, with its myriad slanting lights, pointed upward in the sky. Their journey was ended.

Very still now stood the cortege. Low and deeply bent stood the silent attendants, as with streaming eyes they gazed longingly upon the slight young figure which the samurai Genji, almost bowed over with personal grief, assisted to alight from the norimono. In her white robes the Lady Wistaria seemed a spirit as she stood there under the moonbeams. Mutely she looked about her. As the muffled sobs of her servitors reached her ears, she wrung her hands with an unconscious gesture of anguish greater than their own.

As if in sympathy with the intense sadness over all who were there, nature herself seemed to show signs of her own distress. Clouds rolled over the skies above the mountains, veiling the moon and the star beams. A little river that flowed at the foot of the hill was heard sobbing as it rolled with a mournful sound over its rapids.

But the lights twinkled out warmly from the temple beyond, and a white-robed priestess was descending to welcome the novitiate. An odor of sweet incense, such as of umegaku or tambo, was wafted to the watchers on the hill from the temple doors. Wistaria turned her face towards it. Then back again she directed her glance to her kneeling servitors. Her voice was as soft and gentle as a benediction.

“Pray thee,” she said, “to take care of your honorable healths. Sayonara!”

She hesitated on the threshold of the temple. Then silently she entered the place of tranquil rest amid the shadows of the mountains.

Chapter XXII

The Prince Keiki had been on the highway three days before he became again something more than an unconscious automaton. After the first great shock of Wistaria’s revelation had passed from him, there had come a desperate terror and horror which seemed to numb his faculties. For several days he was not conscious of anything within or without him. There was no anguish in his heart or intelligence in his brain. His memory of events succeeding Wistaria’s unmasking, as he believed it, was as vague as the tangled threads of a dream. He had fallen into that apathetic lethargy with which he had been afflicted upon his arrest.

He had, it is true, uncertain recollections of a place passed on the way, or of a halt here and refreshment there, but he could not assert that they were real. He might have dreamed them. He could not tell.

Then Keiki returned to his normal being. He awoke as from a trouble sleep to a world of torment. Could he have slept, and sleeping, have imagined the events with which the name Wistaria was repulsively associated? No! It was, alas, all too true. He must bear it. As the first sharp anguish of his awakening passed away, there came visions to comfort Keiki.

When what he termed in after years his great awakening burst upon him, he found himself walking down a muddy road which led, his sense of locality told him, south to his province of Choshui. It was raining, fiercely, sullenly. Almost with a feeling of relief, Keiki found that he was wet. It gave him new life and new courage to do some simple elemental thing, such as drawing his cape tighter, closer about him. Then, as he battled against the wind and the driving rain, a fierce joy came to him. He was wise in the wisdom of suffering. His life should be devoted to the cause. No woman should destroy the significance life held for him.

Too long had he tarried with inclination. He had pictured to himself a beautiful highway through life, upon which Wistaria should tread by his side. She was lost forever. The rough path, the developing path of struggle, should be his. He would not falter. He would be true first to himself, his higher self, and then to the holy cause of his country. Patriotism and the restoration of rightful rule to the Mikado should guide him in every act. The events through which he had passed had consecrated him anew. His life could not be taken; he could not fail, until all had been accomplished.

In the new life which he was about to enter his course would not always be plain; he would not always be understood. For that he must be prepared.

When the Prince Keiki had thus settled the past and ordered the future, he began to take cognizance of outward conditions, as became him now. It was wet, and growing dark. He must seek shelter for the night. Turning aside from the highway, Keiki asked the simple hospitality of the country-side from a little house hard by the path of travel. Although it was long past the hour of their evening meal, the good dwellers in the cottage, sent their daughter to the rear of the house to prepare food for the hungry Prince.

Sitting alone in a corner, Keiki, waited upon by the little maiden, found a quiet and comfort that three days ago he would have thought impossible. A strange comfort exhales from a perfectly appointed meal after the heart has been tried. It is the acme of despair, the realization of one’s duty to one’s self. Keiki, absorbed in these fantastic reflections, suddenly became conscious of the fact that for several minutes past the little maid had been making strange signals to him. Seeing this, he signed to her to advance. She did so, but in a faltering and almost fearful fashion. When near enough to him to speak without being overheard, she glanced in terror at his face and slipped to the ground, where she prostrated herself at his feet, her head nodding in frantic motions of servility.

“Why, what is this?” ejaculated the Prince, displeased.

“Y—your highness!” she gasped.

“Speak,” said Keiki, sternly. “You appear desirous of serving me. What is it?”

She rose tremblingly.

“You must not tarry here long,” she whispered. “The spies of the Shogun are about.”

“Ha!”

“It is broadly reported that the Shining Prince Keiki has escaped his fate. The roads are beset. They are tracking his footsteps. Even now some of them are before the house. Oh, my lord, I know you to resemble too closely the Shining Prince for you to linger here. We—the whole country—are in sympathy with thee and would befriend thee, but the shogunate—” She broke off, her fear and distress completely overpowering her.

Keiki laid an alert hand upon his sword.

“None may take me now,” he said, defiantly, “for I am become invincible.”

“Come!” urged the little maid.

“Whither?” inquired the Prince.

Pushing aside the doors at the rear, she led Keiki into the garden. Passing through it, they came to a wall. The maid spoke.

“Climb this, turn to the west. Go along the road a bit until you come to a cross-path. Take that, and you will come out upon your southern route below the danger point. I—”

There was a movement in the bushes, behind.

“Oh, all the gods!” she cried. “It is too late, I fear!”

“What do you there?” a voice stern with threatening, demanded from the bushes. The maid responded:

“Peace to thee! I do but bid farewell to my lover.”

A laugh answered.

“Do not fear, maiden. We do not disturb cooing birds,” came from the bushes, and a drawn sword was shifted from hand to hand, carelessly. The warm blood surged about the temples of Keiki. Because of the perfidy of Wistaria, he would accept no service from her sex.

“I did not need thy lie, maiden,” he said.

Then to those in the bushes he shouted:

“I am he whom you seek, the Prince Keiki. Come, take me!”

As he spoke, he hurled his cape to the ground and rested his sword with its point upon his sandaled foot. Quick as was his action, it was met by those lurking in hiding. Three forms glided out from the bushes. Three blades flashed towards him. Keiki’s quick eye perceived that those attack him wore but one sword. They were evidently merely Shogun spies or common soldiery. Their clumsy handling of their swords filled his soul with a wild elation. He would have some play with these vassals—he, Keiki, the most exquisite swordsman in Japan, and the most finished Jiujutsu student.

“Come hither—hither!” he taunted. “Without dishonor ye may yield yourselves to me, Keiki, the invincible!”

A savage yell replied. In imagination, perhaps, the Shogun spies saw the glittering price of the Prince’s head within their hands. They closed with him.

The hand of Keiki instantly snatched the second sword from his belt. With a sword in each hand he met the advance. The sword in his right hand met and parried the initial blows and thrusts of his two adversaries; the sword in his left met the blade of the third, and though it could not attack, maintained an effective defense.

The attacking swordsmen were startled. Such a thing was beyond the traditions of the samurai, and a feat well nigh impossible.

Of a sudden the blade of the first of Keiki’s adversaries dealt a vicious blow. Keiki met it with his left-hand sword, and before the blade could be recovered by the enemy the sword in his right hand had turned to the second adversary. This one, unprepared for Keiki’s sudden onslaught, fell back, with his sword-arm severed at the wrist. Again the first antagonist thrust; Keiki met him. He now had an antagonist on either side of him, at points nearly opposite. He answered the blow of the one with the first of his two swords, while the other recovered his blade. There could only be one issue to such unequal combat. The position of his adversaries would not permit Keiki to fight them with one sword alone. Alive to the necessities of his position, Keiki kept slowly turning as his opponents tried to take him from behind. Suddenly Keiki fell upon his left knee, as though overcome, while with his right-hand sword he kept up a vigorous attack. The sword in his left hand became feebler, weaker in its movements. Thinking Keiki affected by some of the numerous small wounds with which he was covered despite his defense, the soldier on Keiki’s left rushed in to dispatch him, leaving himself but poorly guarded. The sword opposed to him became swiftly active. It passed into the breast of the samurai, where Keiki, glad that its necessity was over, allowed it to remain.

Quickly regaining his feet, the Prince devoted himself to his remaining enemy, who was a better swordsman than the others.

“Yield!” threatened Keiki, as he dealt a furious blow at the other’s head.

His antagonist laughed. Immediately Keiki thrust in quick succession at the other’s breast, head and throat. His first blow was parried. The second at the head was a feint. As the soldier raised his sword to meet it, Keiki unopposed, thrust through his throat. He fell.

Breathing heavily from his exertion, Keiki looked about him for the maid, and the spy whose hand he had severed. He found the maiden bending over the lifeless body of his antagonist. From her hand a small dagger slipped to the ground. Satisfied as to her safety, Keiki quickly drew out his left sword from the breast of his opponent. Then without a word he climbed the wall and took the southern route again, disdaining to follow the directions of his late hostess.

In a rice field farther down the road he bound up his wounds with the torn lining of his haori. Through the larger part of the following day he slept.

Alarmed by the recent occurrences at the little house by the highway, Keiki, who believed that the Shogun had put a price upon his head, now traveled only at night. The days he spent in sleep, and in locating, without exposing himself too much, the scenes of foraging expeditions made at night through which he managed to secure the means of sustenance.

The vigorous and unnatural fight through which he had just passed had a further invigorating effect upon him. Before that he had been near to death in his thoughts—death for the cause. Now he resolved in fresh and vigorous determination to live—and to live gloriously for the greatest cause that had ever made a pulse to leap in Japan.

At dusk on the fifth day after the fight, Keiki set forth upon the last stage of his journey. He was now near to the borders of the Choshui province. A few hours later he reckoned that he had crossed the boundary and was well within the limits of his father’s country, when there came to him the sound of swords clashing beyond a turn in the road. Keiki, now grown cautious, skirted the spot through a field, and then crept within sight of the place.

Five men were pitted against three, while on the road lay the bodies of two more. Keiki had made up his mind to aid the lesser party, when an exclamation in well-remembered tones came to him. It was from one of the lesser party, old Hashimoto, a trusted follower of his father.

In a moment Keiki was in the road. Before either party were aware of his presence, he had killed two of the larger number.

“I aid thee!” he shouted, as with his father’s men he engaged the despised Shogun followers. Speedily another of their number fell. The four obtained the easy surrender of the others.

Hashimoto approached the Prince.

“We thank thee for thy aid—” he began. Then, recognizing Keiki, he started back a pace and fell upon his knees.

“My noble prince! My master!” he cried, as he caught his robe and reverently pressed it to his lps.

“Thy master?” repeated Keiki. “My father, what of him?”

“Taken, your highness.”

“Taken?”

“After the rumors of your capture, your highness, we at once determined to raise the Imperial standard against the Shogun, and your father—”

“But we were not ready. None of our plans had been carried out!” cried the Prince.

Hashimoto answered:

“True, your highness, but your father was promised the assistance of most of the southern clans. Consequently he seized a number of Buddhist monasteries and cast their huge bronze bells into cannon. His undertaking was revealed to the Shogun before our allies could join us, and he was surprised and taken captive.”

“He serves a sentence?”

“He was sentenced, your highness. But the gods have anticipated—he is dead.”

Keiki threw off his cape, which Hashimoto respectfully lifted.

“Attend me to the fortress,” he commanded.

The followers bowed deeply. Suddenly Keiki raised his voice.

“Daigi Meibunor! The Shogun shall die!” he cried.

The followers answered with a cheer.

With head bowed in deep thought Keiki led the way towards the principal fortress and castle of the Mori.

To Be Continued Next Sunday